Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

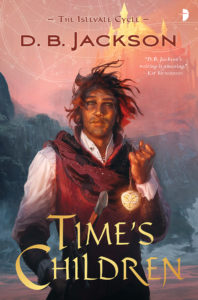

An hour-long conversation with David B. Coe/D.B. Jackson, award-winning author of more than twenty books, including epic fantasies, urban fantasies, historical fantasies, and more, and as many short stories, with a special focus on Time’s Children, the first book in The Islevale Cycle, published by Angry Robot Books.

Websites:

davidbcoe.com

dbjacksonauthor.com

Twitter:

@DavidBCoe

@DBJacksonAuthor

Facebook:

David B. Coe

D. B. Jackson

The Introduction

David B. Coe is the award-winning author of more than twenty books — including epic fantasies, urban fantasies, historical fantasies, media tie-ins, and a book on writing — and as many short stories. His work has been translated into a dozen languages. As D.B. Jackson he writes The Islevale Cycle, a new time travel/epic fantasy series from Angry Robot Books. The first book, Time’s Children, is just out. The second novel, Time’s Demon, will be out in May 2019. A third book, Time’s Assassin, is also in the works.

David B. Coe is the award-winning author of more than twenty books — including epic fantasies, urban fantasies, historical fantasies, media tie-ins, and a book on writing — and as many short stories. His work has been translated into a dozen languages. As D.B. Jackson he writes The Islevale Cycle, a new time travel/epic fantasy series from Angry Robot Books. The first book, Time’s Children, is just out. The second novel, Time’s Demon, will be out in May 2019. A third book, Time’s Assassin, is also in the works.

D.B. also writes the Thieftaker Chronicles, a historical urban fantasy set in pre-Revolutionary Boston. The first volume, Thieftaker, came out in July 2012 from Tor Books. This was followed by Thieves’ Quarry (Tor, July 2013), A Plunder of Souls (Tor, July 2014), and Dead Man’s Reach (Tor, July 2015). In addition to the novels of the Thieftaker Chronicles, D.B. has written and published several short stories set in the Thieftaker world. Many of these have now been gathered in a collection called Tales of the Thieftaker (Lore Seekers Press, 2017).

As David B. Coe, he has published a contemporary urban fantasy series called The Case Files of Justis Fearsson. (Spell Blind, His Father’s Eyes, and Shadow’s Blade. All were published by Baen Books. He has also written several epic fantasy series, including the LonTobyn Chronicle, Winds of the Forelands, and Blood of the Southlands.

David B. Coe was born in New York, and has since lived in New England, California, Australia, and Appalachia. He did his undergraduate work at Brown University, worked for a time as a political consultant, went to Stanford University, where he earned a Master’s and Ph.D. in U.S. History, and finally returned to his first love: writing fiction.

D.B. is married to a college professor who is far smarter than he is, and together they have two beautiful daughters, both of whom are also far smarter than their father. Life’s tough that way. They live in a small college town on the Cumberland Plateau.

The Episode:

We begin with a shout out to When Words Collide, “just a wonderful convention,” and DragonCon: “Mardi Gras for geeks.”

We begin with a shout out to When Words Collide, “just a wonderful convention,” and DragonCon: “Mardi Gras for geeks.”

David grew up loving stories and knew early on in life telling stories what he wanted to do for a living. He got interested in Fantasy after being cast as Bilbo in The Hobbit at a summer camp. He became totally enamored of the genre and Tolkien after that.

He took a workshop-style writing class in high school which enjoyed, and went to college intending to be a creative writing major—but then found himself in a workshop where everyone hated genre fiction and picked on the kid who was writing it, so he got away from writing for a while, to the tune of four years of college and six years of graduate school getting a PhD in history.

After that he had several months to apply for academic jobs, and his wife, who had already taken an academic job, said, “You have all summer, why don’t you try writing and see if you prefer that to history?” He ended up writing the first five chapters of what became Children of Amarid, the first book in the Lontobyn Chronicle, which won the Crawford Award and launched his career.

One Thursday in March he was offered a job teaching history–and the very next day he heard from Tor, wanting to buy his novel. He had the weekend to “decide what I wanted to do when I grew up.” He decided he wanted to pursue a writing career, and hasn’t looked back.

He says it was a hard choice at the time, but absolutely the right choice, and he continues to find his academic background in environmental U.S. history valuable in worldbuilding.

He creates his own maps, and mentions when he was still a newbie he ran into George R.R. Martin at a convention and told him he was working on something new. Martin asked to see his map, looked at it for about two minutes, and then said, “That’s a good map.” David says he was “flying for the rest of the comvention.”

The world of Islevale in which Time’s Children is set is a world of islands and archipelagos, meant as an homage to Ursula K. Leguin’s Earthsea, one of the earliest fantasies David read, and one he fell in love with.

After synopsizing Time’s Children (you can read a synopsis here), David explains where the D.B. Jackson pseudonym came from. He’d been writing epic fantasy for Tor, and when he switched over to the Thieftaker books, urban fantasy with a historical element, Tor was concerned about branding, so D.B. Jackson was known. Now he’s probably better known as D.B. Jackson than David B. Coe. Angry Robot was given the choice of bylines for Time’s Children and liked the critical response he’s received under D.B. Jackson. so went that route.

D.B. are, of course, his first two initials. His late father’s name was Jack, so Jackson is his way of honouring him.

David says he’s unaware of another fantasy novel dealing with time travel, which is usually done in a science fiction setting. There’s the Time Turner in the Harry Potter books, but David says (as a fan of the books), it’s a terrible device, used poorly. “If time travel is that easy,” he says, “why are Harry Potter’s parents dead, and why is Voldemort still alive?”

He sought to make time travel difficult–physically costly for the person doing the travel–and incredibly rare. There are not a lot of “Walkers,” they pay a terrible price, and the process i harrowing. (The main price is that they instantly age however many months or years they travel back in time–and again when they return.)

David thinks the book started with the idea of being a child in a man’s body, of intellect and emotion being out of sync with the body. He remembers holding his infant daughter worrying about the fact he was no responsible for her when he felt barely more than a child himself.

“I wanted to tap into that sense of taking on responsibility that we’re not ready for.”

David says his process of worddbuilding is to ask questions of himself in a stream-of-consciousness fashion. Although he usually outlines very closesly, Time’s Children resisted that. “The process was more fraught and more difficult and more harrowing than any other writing experience.” He says he was winging it much of the way, and “winging it” in a time-travel story meant “my brain nearly exploded.” It also meant a huge rewrite at the end because “I’d fouled up so much of it.”

In the end, though, the challenge was worth it, even though at the time it was deeply frustrating. He mentions that when it comes to creative process, every writer works differently, and on every project the writer is forced to kind of reinvent that process. He also says that while there are things you can teach students of writing (he teaches writing quite often), when it comes to process, all you can do is offer suggestions and describe what works for you.

He says Time’s Children was the hardest book he’s ever written. He spent six months trying to outline it, until his wife said he should just write it; then, when he sent it to his agent, his agent said, “It’s not there, here’s what missing.” It took him another several months to tear the book down and rewrite it, but all that hard work makes the finished product more gratifying: he believes it’s the best book he’s ever written.

He adds that even when he’s doing his most detailed outlining, maybe a paragraph per chapter, the outlines remain fairly loose because he knows that when he gets halfway through he’ll have to re-outline because things have changed. “I like to create in the moment.”

Still, he says, “I need to know where I’m going,” and with Time’s Children he felt hw as “groping through the darkness.”

David has written novelizations (like the novelization of Robin Hood). For that he was working from a script and given very little creative leeway. He calls it “color-by-numbers” writing, and while he was thankful for the work, he didn’t find it fun: it was slog (but a fast one–he only had five weeks).

He’s now working on a novel-tie in for the History Channel series about the Knights Templar, called Knightfall. That one, he’s finding fun.

He does a fair amount of research for any project. For the Islevale books, he had to research boats, since he decided to do an Earthsea-style world, and things like weaponry and sea currents and navigation.

He remembers once spending hours to research wheelwrighting because he’d decided to make a character a wheelwright. In the end, it was only a one-page scene. “But I wanted to get it right…even if we don’t include all the things we learn in our research, the weight of that knowledge can be conveyed in just a few lines…One detail can bring so much authenticity to the entire scene.”

He sees character work as another form of worldbuilding, and researches them the same way. He creates detailed character sketches, and sometimes writes short stories (which he can sometimes sell) to develop them further.

For example, there’s a non-human character called Droë in the Islevale books, a time demon. He wrote a short story about her called “Guild of the Ancients” which was published in ana nthology.

David believes the ability to step into the emotions and thought processes of characters is the same thing that makes us good fathers and husbands and friends and siblings. “That’s what makes us helpful to the people we love in our daily lives, that ability to stretch our empathy to the point where we’re taking on their emotion.”

Because of the ages of the characters, Time’s Children might at first glance appear to be a young adult novel, and David was fine with that. “Write the novel you want to write, and when you’re done, then you figure out how you market it. ..I was aware with the romance, and even a romance triangle of an odd sort, I was writing something akin to YA novels.”

However, while there are themes that cater to a YA audience, there are also themes that an adult audience is drawn too. And, he adds, the second book, Time’s Demon, is not a YA novel at all: it’s serious and dark and also sexual in a certain way. “My editors were aware of this, they knew not to market it as a YA.”

Returning to the notion of feeling young in an old body, David says he and his wife have biologist friend who, when he was young, studied mating habits in birds, and as he got older has started studying aging patterns in birds. “Our professional lives often mirror our emotional interests and concerns.”

David is “a middle-aged guy,” and he remembers thinking, when he was in high school, that when he was his parents’ age he would feel very different because they were so old. But now that he is that age, he doesn’t feel all that different. ” I feel I’m the same person I was twenty or thirty years ago. Certainly still immature…This idea of aging but still feeling the same internally was speaking very powerfully to me.”

Baby Sofya is a major character in Time’s Children. David says that, for all the demons and assassins and time travel and magic in these books, they’re also very serious to him because they’re about family: creating family out of the ashes of chaos and loss and tragedy and violence. They’re rebuilding family in order to keep this infant alive.

He says there’s something about the uncompromising needs of a baby that creates exigencies with which your protagonists cannot negotiate: the baby must be fed, changed, carried. It both creates intense stakes for the characters and yet also offers a certain lightness. “I’ve loved writing Baby Sofia in these books and making her central.

David says there was a lot more rewriting of this book than he usually has to do, but it was not so much a matter of the writing as the plotting. Almost all of the notes he got back from his agent had to do with narrative structure, and that was one of the best lessons he learned in this book. He was proud of the prose, which he thought sparkled: the trouble was, it didn’t “crackle.” There was no energy in it: it was all about his main character, Tobias, hiding, and it needed to be more about him being proactive. In the end, David cut 40,000 words, and then added back 60,000, totally changing the feel of the book.

Members of his writing group (the first he’s ever belonged to) provided valuable feedback, especially since none of them are fantasy writers and only a couple of them even read it. “They were able to show me places where my worldbuilding wasn’t clear enough or magic system bogged down in details too heavy for non-genre readers.”

Some of that advice was contradictory, but as he tells students, in the end, the book belongs to the writer. “There are going to be mistakes. They’re going to be my mistakes.” He says he’s all for the idea of “killing our darlings,” but ultimately the book has to speak to him as the author. “When I got contradictory advice I followed my heart and followed what my characters were telling me.”

Angry Robot is a new publisher for David, so he had a new editor, Nick Tyler, who also provided valuable input, although by that point the book was so clean “it didn’t need a lot.” He expects more editorial developmental work on the second book. “I’ve been working on it for a while, but I need fresh eyes.”

David agrees that literary fiction worlds are every bit as made-up as genre fiction worlds. “Every time we create characters and circumstance for those characters we are venturing into make believe. The distance between what I do and someone who writes realistic fiction isn’t that great.”

He says the prejudice against genre fiction has to do with either the notion that genre fiction is formulaic (which David rejects) or that somehow genre writers using plot tools like magic and time travel in place of character, setting, or narrative cohesion, as if writing is a zero-sum game, so that if you add in these other elements you have to take out something vital. He rejects that, too. “I don’t think if I add magic I have to take out something vital from the work.”

He says, “We’re still writing about people, still dealing with human emotion, conflict, tension, all the things that make day-to-day experience something we want to write and read about. I do think its an unwarranted denigration of our genre and other related genres. Writing books is hard.”

If writing books is hard, why does he do it?

Davie laughs. “If I don’t, those voices in those heads are going to keep talking to me, and Im going to go from being a professional to being an out-patient.”

He says he has stories, characters, and ideas he wants to share. “For all the struggles, for the bad pay and the poor reviews and all the other struggles, I love, love, love what I do. I can’t imagine doing anything else, I can’t even imagine wanting to do anything else. Every day I get to sit down at a computer and say lets pretend. What job could be better than that?”

He also feels speculative fiction can have an impact on the real world, by holding up a mirror that allows us to explore issues of race and gender and environmentalism and class and social injustice and all sorts of other important political and social and cultural issues in ways people have never thought of before. He mentions Neil Gaiman’s American Gods, a prescient book that predicts the rise of social media in our society, and Nora Jemisin, who is writing about social issues, gender, and race “in ways that can teach us so much about our world and how we can make a better world for our children.”

He’s written about environment, race, and mental illness, not because he’s trying to send out a social message or bludgeon his readers with politics, but because he believes writing should be about a lot of different issues.

Up next for David: Time’s Demon, the Knightfall novel (out in March), and editing an anthology, Temporally Deactivated, for Zombies Need Brains. Later this year he’ll be starting work on Time’s Assassin, book three in the Islevale trilogy, and he’s also got a couple of short stories to write. “I’m busy, and busy, for a writer, is good.”