Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

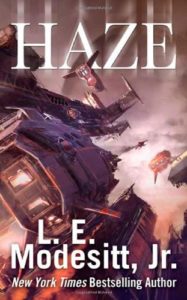

An hour-long conversation with L. E Modesitt, Jr., bestselling author of more than seventy novels of fantasy and science fiction, including the Recluce Saga, the Spellsong Cycle, the Imager Portfolio, and more, about his creative process, with a special focus on his science fiction novel Haze.

Website:

lemodesittjr.com

L.E. Modesitt Jr.’s Amazon Page

The Introduction

L. E. Modesitt, Jr. is the bestselling author of more than 70 novels, encompassing two science fiction series and four fantasy series, as well as several other science fiction novels. He has been a delivery boy, a lifeguard, an unpaid radio disc jockey, a U.S. Navy pilot, a market research analyst, a real estate agent, a director of research for a political campaign, a legislative assistant and staff director for U.S. congressmen, director of legislation and congressional relations for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, consultant on environmental regulatory and communications issues, and a college lecturer and writer-in-residence. In addition to his novels Lee has published technical studies and articles columns poetry and a number of science fiction short stories. His first story was published in 1973 we’ll find out about that in the course of the interview. He lives in Cedar City, Utah.

L. E. Modesitt, Jr. is the bestselling author of more than 70 novels, encompassing two science fiction series and four fantasy series, as well as several other science fiction novels. He has been a delivery boy, a lifeguard, an unpaid radio disc jockey, a U.S. Navy pilot, a market research analyst, a real estate agent, a director of research for a political campaign, a legislative assistant and staff director for U.S. congressmen, director of legislation and congressional relations for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, consultant on environmental regulatory and communications issues, and a college lecturer and writer-in-residence. In addition to his novels Lee has published technical studies and articles columns poetry and a number of science fiction short stories. His first story was published in 1973 we’ll find out about that in the course of the interview. He lives in Cedar City, Utah.

The (Lightly Edited) Transcript

We’re going to focus on Haze, but first: how did you start writing fiction and how did your interest in science fiction and fantasy develop. Was this a childhood thing or did it come along later?

I always was interested in science fiction and fantasy. I started reading it at a very young age and actually my mother was the one who introduced me to it. My father was an attorney and he didn’t have much interest in that sort of sky-blue stuff that just wasn’t hard and fast, whereas my mother was much more of a speculative mindset. And we lived in what was then the countryside, so to speak, and we weren’t close to libraries and we weren’t close to stores. But she did have this great painted bookcase in the front of her bedroom, and it was filled with paperback science fiction novels. And seeing as there was nothing else much interesting to read—I wasn’t going to read my father’s law books—I started reading science fiction But I never really thought I was going to write it. As a matter of fact I, was going to be the next William Butler Yeats, because my interest initially was in poetry. I read poetry, wrote it, did projects on it, essentially had a minor in it in college, although it wasn’t called that because they didn’t offer that minor, but I actually spent two years studying under William Jay Smith who later became the poet for the congressional reference service in Washington D.C., and that position then became the poet laureate of the United States. And I wrote poetry for some 15 years before I even thought of writing science fiction.

I always was interested in science fiction and fantasy. I started reading it at a very young age and actually my mother was the one who introduced me to it. My father was an attorney and he didn’t have much interest in that sort of sky-blue stuff that just wasn’t hard and fast, whereas my mother was much more of a speculative mindset. And we lived in what was then the countryside, so to speak, and we weren’t close to libraries and we weren’t close to stores. But she did have this great painted bookcase in the front of her bedroom, and it was filled with paperback science fiction novels. And seeing as there was nothing else much interesting to read—I wasn’t going to read my father’s law books—I started reading science fiction But I never really thought I was going to write it. As a matter of fact I, was going to be the next William Butler Yeats, because my interest initially was in poetry. I read poetry, wrote it, did projects on it, essentially had a minor in it in college, although it wasn’t called that because they didn’t offer that minor, but I actually spent two years studying under William Jay Smith who later became the poet for the congressional reference service in Washington D.C., and that position then became the poet laureate of the United States. And I wrote poetry for some 15 years before I even thought of writing science fiction.

As matter of fact that I was turned down with form rejections from the Yale Younger Poets contest every year until I was too old to be a younger poet. Then I was in my late 20s, and my first ex-wife basically suggested that maybe I should try something besides poetry and she suggested science fiction, since I read it.

So, I thought I could try that, and I wrote a short story and I sent it off to Ben Bova who has just taken over as the editor of Analog, and he sent back a rejection. The rejection letter said this isn’t half bad but you made a terrible mess out of page 13. It’s good enough that if you can fix it I’ll look at it again.

I did, and he bought it. (The title was) “The Great American Economy.” I was an economist by training and it seemed like a good place to go. It took me something like somewhere in the neighborhood of another 26 stories before I could sell the second one. And it was maybe 17 or 18 before I sold the third one. And this went on for maybe, I guess, five or six years, and then Ben sent me another rejection letter, and it began with the words, ‘Don’t send me any more stories–I won’t buy them.’ And after I got over the shock of those, I looked at the next paragraph, which said, ‘it’s clear that you are a novelist trying to cram novels into short stories. Go write a novel. After that we’ll talk about stories.’ Now, I hadn’t wanted to write a novel. At the time I was working as, at that particular point, legislative director for a U.S. Congressmen in Washington. Long hours, and I didn’t want to write a half million words to sell ninety thousand. But Ben didn’t give me any choice. So, I wrote a novel, and it sold, and that’s another story, but it did sell and every novel I’ve ever written since then has sold, so Ben was absolutely right about the fact that I was probably a better novelist than a short story writer.

How old were you when you started writing poetry?

I started getting published when I was about 15, only in small literary magazines.

There’s not a lot of other markets for poetry except small literary magazines anymore, is there?

Well, there is, I mean, you can theoretically publish it in The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, and a few other places like that, but that’s about it.

Did your poetry have any elements of the fantastical?

Oh, I think I one or two maybe had a few hints of the fantastical in it. I did write one poem, as I recall, about Atlantis, so I guess that had a certain fantastical element to it, but most of them weren’t.

Do you still write poetry?

Oh, yes. And I’ve incorporated into a lot of my novels. I mean, there are two novels in the Recluce series that are literally linked together by a book of poetry and the resolution of the second novel is partly shaped by that poetry and the existence of that poetry.

What part of the country did you grow up in?

I grew up in the suburbs south of Denver, Colorado. When I was very young my father decided he wanted to practice law in Hawaii. So, we moved to Honolulu and we lived there for a year and a half. He decided it wasn’t the best place to practice law or raise children, so we moved back to Denver, and we lived there until I went away to college.

Where did you go to university?

I went to Williams College in Massachusetts. I studied Economics and Political Science, a double major.

That sounds like the sort of thing that would help you with the creation of societies in science fiction and fantasy. Is that true?

Oh, I think it helped a great deal. Plus, 20 years, or 18 years, in the national political arena certainly didn’t hurt any. And I had a couple of years, actually a year, as n industrial market researcher, which was basically economic, and it was probably the most boring job one can possibly imagine, because my job was to forecast the sales patterns of compressed air filters, regulators, lubricators, and valves.

It sounds utterly fascinating. Have you ever gotten a story out of that?

I never could make a story out of that one. I’ve made stories out of a few other jobs I had but not that one.

You were also in the U.S. Navy for a few years and were a pilot. What kind of aircraft did you fly?

Actually, I started out as an amphibious officer, and I hated small boats so much that in the middle of the Vietnam War I volunteered for flight training, and the Navy decided I was a decent pilot but not a great pilot. So, I ended up flying helicopters and was a search and rescue pilot.

In Haze, the character is a military man of sorts. Does your military experience play into your writing, as well?

Oh, absolutely. I mean, I’m not certainly extensively a writer of military science fiction, but the military does fit into an awful lot of my books in one way or another. Maybe 40 percent. That’s just a guess, but yeah, it’ been a big factor.

I seem to remember that at ConVersion, the Calgary convention where we first met, you talked about economic systems in fantasy and science fiction and how there are a lot of unworkable ideas of how societies might work. Is that something you like to bring into your fiction, trying to create a more realistic society?

That’s exactly how I got into writing fantasy. I wrote strictly science fiction for almost the first 20 years I was writing. I got into writing fantasy because I got really tired of all of these fantasies where people go off on quests with no visible means of support, or where there are 10,000 armed knights on a side. One of the things that it dawned on me in terms of writing fantasy is, almost never, especially in the fantasy that was being published when I first started writing, did anybody have a real job. And one of the things that I’ve done in all my fantasies and which is still very rare is, all of my characters and fantasies have real jobs. They have to make a living. And the magic system has to be monetized. This is still very rare. A lot of people basically have a character, “Oh, he’s got a real job, but he’s on vacation or the job gets lost. And they just go off with the fantasy stuff.” When I’m writing fantasy, the economics and the magic are all integral. Maybe it’s because I was trained as an economist, maybe because I’ve been in politics, but I realized something about, call it technology, and that is, we don’t hang on to technology. We don’t use it unless it’s good for one of two things. It’s either a tool that will make somebody money or it will entertain somebody.

Well, magic would be the same way. If magic were real, nobody would bother with it unless they could do something with it, make money out of it or if they could entertain people, because we as a species are tool users. We are pretty much pragmatic but we like to be entertained. So, if magic can’t do one of those two things, it’s not really gonna be terribly useful in a society. And that’s probably too much of a soapbox. But anyway, that’s where I’m coming from.

It seems like there’s a preponderance of people are like thieves, bards, or mercenaries. That seems to be the three going job opportunities in a lot of fantasy worlds.

I think part of that is because people don’t think through what fantasy and magic can be used for. I do think that in my fantasies I come up with, shall we say, both practical and ingenious ways of using magic because people would.

Well, I’ve been accused of writing fantasy with rivets, so I’m not sure I agree with that one, but my feeling is, it’s simply the ground rules. In science fiction, the ground rules are, shall we say, the standard model of physics, if you will, and in fantasy, it’s whatever set of, call it a universal operating system, the author wants to put together. In the Recluce books my operating system is the balance between order and chaos

I basically use a different operating system for each fantasy universe, but I make a great effort to be rigidly consistent with the operating system, whether it’s science fiction or whether it’s fantasy. But beyond that I don’t treat them any differently. The characters just have to work within the operating system.

Let’s talk more specifically about your novelHaze. I’ll let you synopsize it so you don’t give away anything that you don’t want to give away.

Well, it’s set roughly 5,000 years in the future. You’ve got a Chinese Federation ruling the world. What used to be the United States is a client state, if you will, of China, and the main character is an American-born intelligence agents agent working for this Chinese Federation. In essence there are, if you will, two and a half storylines, although both of the storylines concern the main character. One’s in the present and one’s a flashback through the past. He’s basically tasked with investigating a planet, which is called Haze, because none of the Chinese federation’s surveillance gear will penetrate the, shall we say, the armada of A.I. spy devices that circle this planet. And he is one of several teams plunked onto this planet to try and discover what’s behind it all. That’s the setup.

What was the genesis of the novel? What was the seed that led to development of the novel?

I honestly can’t tell you, except part of it was the idea of what would happen if China continued on its present course, and American politics continue on their present course. The Chinese have always tended toward imperial states of one sort or another, and they tended to be both ruthless and bureaucratic simultaneously and that I guess was the background that I created and they pretty much co-opted every culture with its tried to co-opt them.

That was the background. And, of course, somebody is going to want to get out from underneath this. And that’s the genesis of the people on ??? or Haze.

Often when you’re talking about science fiction, there are the two big questions that start a story off, “What if?” and “If this goes on.”

I’m a big believer in the what if.

That’s a very long time in the future, five thousand years.Did you feel that you captured the changes that you’d have in technology and all that sort of thing over that amount of time?

I think a lot of people would say, “Why isn’t it more fantastic?” Well, people forget how fantastic things are right now. For example, we now communicate as fast as it is possible to communicate on a planet. We have essentially pretty much instantaneous communication—if we have the technology. but the ability is there—anywhere on the planet. We can get to any place on the planet in a matter of hours. There’s not that much difference in terms of the culture and the society between, even if we had matter transporters, between instantly and a few hours. There is a huge difference between a few hours and weeks or months, as was once the historical case. You can analogize all of these things to, there’s only so much further ahead you can go with technology. You can’t talk any faster than instantaneously, and it takes a certain amount of energy, no matter what you want to do to create things.

Theoretically, we could, I suppose, put together food replicators that could create anything from constituent elements, but the technology and the energy required…well, with that, it’s a heck a lot cheaper to simply go to Natural Foods. I don’t think you’re going to see changes in those things. So, basically, yes the society I postulated is much further ahead. I did suspect that the Chinese, and I did this in 2010 before this became well known, that the Chinese would find a way to, shall we say co-opt the Internet, and pretty much move into a world spy state. And I also postulated that certain parts of the world would not be at that point inhabitable for various reasons.

I also wondered if part of what you were going for was that it is a very static society. The federation is very static and doesn’t seem likely to evolve very quickly if at all, which I suppose is also a feature of Chinese Imperial States over the centuries.

Well, it’s not only Chinese Imperial States, but I mean, if you go back to ancient Egypt, which was in essence a water empire, that actually is the longest period of maintaining a similar government structure in human history that we know of. It’s actually outlasted the Chinese. I mean, yes, there are pharaohs, and you have the first dynasty and the second, all of these various dynasties, but basically, governmental structure in Egypt stayed pretty much the same from like 4,500 B.C. through the time of when the Romans finally conquered it, and even into Tomake ? Egypt it was somewhat similar.

How do stories tend to come to you?

Sometimes it’s just thinking about thing but probably a lot of it comes from the fact that I still study a huge amount of both history and technology. My wife laughs. She says that every time the mailman comes to our house he heaves a sigh of relief, because of the amount of periodicals we take. I admit that I like print periodicals because I can browse them at odd places at odd times. I think I take three archeology magazines, a couple of history magazines, and a lot of technology magazines, economic magazines. Of course, my wife takes all sorts of music periodicals and I read them all. I’m not sure I could say, oh, gee, this story came from this particular point.

I think the best resource that an author can have is a well-educated subconscious. We don’t remember all of it consciously. You can maybe call it up, but you don’t remember everything that you read. But I’m convinced that your subconscious, or your latent memory, if you will, remembers most of it, and the more stuff you pile in there the more likely you are, at least I believe so, to come up with good ideas.

Do you read a lot of other fiction or do you mostly read non-fiction?

At one point, even before I started writing, I was probably reading four to six hundred science fiction books a year. Right now, it’s more like 40 to 50. Most of my reading is non-fiction. Now I’m fortunate. I can I can read very quickly and I can retain most of what I read. which I find is a tremendous advantage.

With that initial idea in mind for any book, how do you go about shaping the world? Do you set out a plot and the characters develop, or how does the process work for you?

Well, it varies a little bit from book to book, but in general I tend to start with the world, the structure of the society, the religion, the environment, those factors, because they shape an awful lot of what you can do with the book. Resources are a factor. How do you get them? Where are they? Who controls them? Geography and obviously religious or belief structures, those shape people and people shape government. And I come up with those sorts of governments.

I mean, it’s not monolithic. When you look at the Recluse series, which is my biggest series, it set across over 2.000 years. And in the course of the 20-plus volumes, there are ,stories set on five different continents and more than 20 countries and the government systems that I have in those countries vary tremendously.There are military matriarchies, trading councils, hereditary monarchies, various other structures, an imperial structure in one particular case, based a lot on their past history and also the cultures and the geographies there.

Do you write all of this down before you start? Do you take copious notes and outline and do a detailed synopsis?

I don’t do synopses. I do have a set of notes when I’m doing a fantasy. I have a rather large-scale, rather large and rather messy, scale map of the countries and the world that I’m working in. I’m very big on scale maps because when I was younger, I got really irritated at writers who over the course of a book had the same journey take quite varying times without any changes in the climate or the cargo or what have you. So I try and be fairly accurate about that. I try and set up a structure that fits and then work within it.

Do you set out the plot in detail before you begin, or does a lot of that happen as you write?

I know pretty much the beginning and the ending. How I get there is something that I have to work out as I go along because you got to work. I mean, there are times when I have gotten to a point in the book and I’ve thought, well I thought this character was gonna do that, but the way I’ve written this character, he or she is not going to act that way. And so, I’ll have to figure out another way for that character to get to that, given their character.

Well, speaking of characters, how do they arrive on the scene to you? How do you decide what characters you need, and then how do you go about bringing them to life?

A lot of that depends. I mean, it’s the chicken and the egg thing. A lot of that depends on the structure and what you’re trying to do. In the first book of the Recluce Saga, I was thinking about Lerris in terms of a very bright but almost Asperger’s-like clueless young man, who was goodhearted. The reason why it was written in the first person, past tense, rather than the third person is, if I’d written in the third person, Lerris would have come off as the most obnoxious self-centered young man you could possibly imagine. He wasn’t. He was good hearted, essentially clueless and dense about a lot of things, but yoou wouldn’t be able to see that from the outside. So that’s one of the ways where the character defines the structure. In other cases, I mean, if you go to Adiamante, which is one of my science fiction novels, it was actually taken from life in a way. An acquaintance of ours in his, shall we say, late middle age, suddenly lost his wife to a fast-moving form of cancer and I started thinking about what would that be like. And then I put it in a science fiction setting, and so it’s really a science fiction novel about a man in either late middle age or early old age who’s had a certain amount of power in the past and is called on to deal with a very difficult situation, because of that expertise, And how he deals with it is intertwined with, call it his grief, and his understanding of where he’s been.

So that’s another way of bringing a character into a story. Soprano Sorceress from the Spellsong Cycle is a music fantasy set in what I would call a Germanic misogynistic society, and I came up with that particular idea because I was thinking about how well today singers are trained (because my wife is a singer and trains them) and what would happen if you had a society governed by song magic, and a lot of things fell into place there because one of the things I realized was even if you had song magic you’re not going to have very many sorcerers or sorceresses. And the reason for this is a confluence of two events that everybody overlooks. First, to really train somebody well as a singer, you really have to train them young. I mean, basically, after puberty and before 30. Second, that’s the most self-centred time in human existence. And if you are going to give somebody the power that could kill you…you’re going to be very careful about who you train. Then you add to this an outside sorceress from our world who’s got all those abilities in a misogynistic society. Well I thought it would make for an interesting conflict and it did.

So, it sounds like a lot of your stories actually arise because of the interplay of the character with the world that you’ve created.

Exactly. But I mean, that’s life. Everything we do is created by the interplay of the character with society and what goes on.

Do you do a detailed character sketch, or does it arise more organically as you write?

I think more I have a feel for the character to begin with. Call it a sense of who he or she is. Then I fill in some of the details and then we start filling in the society and the conflicts. And it goes from there.

A lot of writers—it’s happened to me—will put in a character simply because, for example, there needs to be view of something the readers need to know about and the main character is elsewhere, and that character then turns into a more major character than anticipated. Does that sort of thing happen to you?

I can’t say that it happens in that fashion, although there have been some characters who were minor characters in one book that I thought, “I really want to find out more about this character,” and so I wrote a book about them.

And usually if you want to find out more about the character the reader wants to find out about the character, too, so that works out.

What does your actual writing process look like? Do you write by hand? Do you write on a computer, do you write on a typewriter? Do you write in an office or in a coffee shop? How does that work for you?

Okay. One, I do not write long hand, I’m left handed. I probably wasn’t trained properly in penmanship. And I get writer’s cramp after 200 words writing longhand. I started writing on a typewriter when I was 15 years old, just for school and what have you. I moved to computers as soon as computers had enough memory to accommodate my style of writing. I write on a computer. In terms of schedule, my wife laughs when people ask, do I have time for writing. She just says, “He writes anytime he can, which is pretty much all the time.” But to be fair about this, I don’t neglect her, because when I proposed to her, I said, “Well, you know, I need time to write. And her reaction was really simple. She just started laughing, and when she finished laughing, she said, “You are going to have more time to write than you have have ever had in your life. And she was right, because basically, she is a classically trained lyric soprano who’s done some work in opera, but she basically runs the university opera program and the voice program, and her schedule is 9 to 10 in the morning until 7 to 11 at night, depending on the time of year. She was right. I have plenty of time to write.

And you’re quite prolific. You’ve done as many as two or three books a year haven’t you?

I’ve averaged two and a half books a year for the last 20-plus years.

That makes me wonder what your revision process looks like. Do you have a very clean manuscript when it’s finished? Do you have to go back and do a lot of rewriting? Do you use beta readers? How does that work for you?

Actually, according to my editors, I turn to a very clean manuscript. I revise continuously as I am writing and then I generally revise again after I’ve finished with the first draft of the manuscript, which is a little misleading, because there are probably some parts of that manuscript that written a dozen times before I finally finish it.

Revisions for me are both fun and by far the easiest part of the process.

As far as editorial revisions, I’ve had the same process with both of my editors, and I’ve only had two editors in the entire time I’ve been in the field. One was David Hartwell, who was my editor from my first book until his death a couple of years ago, and the second is my current editor Jen Gunnels, who was David’s assistant, and I’ve been working for her for about a year and a half before David died and she and I worked together well so I just stayed with her. But in terms of dealing with the editors, I’ve always had a very simple formula. Find anything you can that’s wrong with the manuscript. Tell me what it is. Don’t tell me how to fix it. Just tell me what the problem is. If I can’t fix it, then we’ll talk. In 40 years I’ve never had to have the second conversation.

You’re at 70-some books at this point aren’t you?

Seventy-three published, three more that will be published in the next year and a half.

Do you do a lot of research along the way?

Yes and no. I do a lot of research, but a lot of the research I’ve done in advance, just simply by all the things that I read. Every once in a while, I’ll have to look up something to make sure that I’ve remembered it or I’ve gotten the details correct.

It’s been said that all men are collectors. I don’t know if this is true, but an awful lot of men I know collect things. I don’t. What I collect is information. I love information. I love learning about things and I think I probably always will. And as an author, it serves me very well.

One of the things about Hazethat this struck me was, you know, we talk about science fiction as a literature of ideas, and it seemed to me that one of the things you were doing in Hazewas offering different views of how society might work, and bouncing these off of each other, through things like freedom and individual responsibility and empire and what happens when societies of different technological abilities clash. Is that kind of a feature of your work?

I’m not sure my work would exist without that. I’m always bouncing various ideas of how people respond to duty. responsibility. political structures. beliefs. I guess in a lot of ways that’s really what I do.

Well, certainly in Haze it comes through quite a lot with the difference between the Federation and the society on the planet.

One thing I would say is that the conflict that you that you’re talking about is a little stronger in my science fiction. It’s a little more subterranean, a little deeper and a little quieter in the fantasy, but it’s there.

How does it break down for you between science fiction and fantasy right now, in numbers of books?

We’re talking, with the ones I’ve turned in 29 science fiction novels, and 45 fantasy novels. In recent years it’s been more than two to one fantasy to science fiction.

Do you find an overlap in your readership between the two? Or do you find you have a science fiction readership and a fantasy readership?

Actually, I’d say I have three readerships. I have a science fiction readership, a fantasy readership, and a readership that does both.

There are definitely more fantasy readers. Sometimes the science fiction readers get a little irritated and say why don’t you write more science fiction stuff instead of that fantasy stuff.

I was on a panel recently at CanCon in Ottawa, talking about the challenges of writing series. Do you find that continuity and keeping everything straight becomes difficult as a series expands?

It’s difficult, but I’m not sure it becomes more difficult the way I do it. I think it would be very difficult done the way the Wheel of Time was done, but most of my series are not exactly series in what one would consider the traditional thing What I mean by that is, the Recluce series is now something like 22 books, but with one exception, there are no more than two books and sometimes only one book about one character. In a lot of ways, the continuing factor in Recluce is the world and the cultures, not the characters. Same thing is true of the Imager Portfolio. There is, in essence, a trilogy, followed by a five-book series about a different character, and then two two-book series. Spellsong Cycle, three about one character, two about another character. The Corean Chronicles was three, three, and two. So I have to keep the world consistent, but I don’t have quite as much to do with keeping the characters consistent over a long arc.

Do you have to go back and reread books when you go back into a series after you’ve written something else?

A little bit, but not a huge amount. Once I get it get back into a series it seems like most of the main threads and the pieces come back to me. I mean, I often have to check up on little details, particularly if I’ve got minor character that carries through the books. Usually with the major characters I can remember, and I have notes on them.

The name of this podcast is The Worldshapers. One of the things I’d like to ask all the guests is, do you hope that your fictional worlds will help shape the real world in some fashion? What impact, if any, would you like your fiction to have on the real world, or at least on your readers within the real world?

That’s one of the reasons why I write, because we tend to get bogged down in the real world, and I speak from almost 20 years in national U.S. politics. When you bring up a problem in the context of the real world, people get hung up with their tribe, they get hung up with everything around them. When you take that same problem and you put it in a fictional world or a fantasy world or a future world, people can look at the problem far more objectively and think, oh, there might be another way to deal with this.

I had a rather hard lesson with this very earlier in my career. With Bruce Levinson, we wrote a book called The Green Progression, and it actually got a review from the Washington Times that said it was one of the best views of contemporary politics ever written. It’s also one of the worst -selling books that Tor ever published. And to me that just proves the point. People really don’t want to look hard and fast at the current political structure, at their beliefs and how they affect the current political structure. They’re locked into it by their neighbors, their culture, their friends. You take the same problem and you put it in a fictional world, they’re much more open minded about it, and I hope somehow that some of what I do in that sense will help people look at these problems in a different light.

Have you had any feedback from readers to that effect?

I have. I’ve had more than a few people say that they wish I had either stayed in politics or got back gotten back into it. But no.

The other big question that I like to ask is very basic, and that is simply, why do you write? Why do you think any of us write? In particular, what do you think is the appeal of writing within the science fiction and fantasy genres, for you, and for anyone?

I don’t know that I can speak to anybody else. I write because I have to write. I wouldn’t be complete without writing. And that’s very selfish, but I try and leaven that with hopefully entertaining people and making them think. One of the things I try and leave all readers with in any of my books is at least a shred of hope, if not more.

There’s certainly a lot of fiction out there that seems to go the other way.

Yeah, and some of it’s very well written, but that’s just not my cup of tea. I think that, especially now, there’s way too much gloom, doom, and despair, and a lot of it is justified, but in the fictional world, I’d just like to give people shreds of hope, and sometimes more.

You’ve talked about in at least one interview I read about how important telling a good story is. Why did what do you think the appeal is of story to people? Why are we so interested in stories?

Because human beings are anecdotal. We have trouble with statistics. We’re innately number hampered. And we don’t really like facts. Stories are what we think about. Stories are what influence us. I can’t tell you why, but I know it’s so. Stories are what motivates us, and I’d like to be one of those doing some of the motivating.

What are you working on now?

I just turned in a very far-future hard science-fiction…actually, it’s a hard science-fantasy novel…entitled Quantum Shadows. The subtitle is Forty-Five Ways of Looking at a Raven. That’s because every one of the 45 chapters is prefaced by a couplet to the Raven. who is one of the main characters. So that’s what just happened.

Forty-Five Ways of Looking at a Raven sounds like a poetry book title.

Well, that’s why the subtitle. That’s why Quantum Shadows is the novel title. But there are only 45 couplets and I have 93,000 words. I think readers can deal with 45 couplets.

Currently I’m writing another Recluce book. It’s about a new character that nobody’s seen, so I don’t want to say much about it because I’ve only written about 65,000 words and I means I have another 120,000 words to go.

What will be the very next thing that’s published?

The next thing that will be published is the last book in the Imager Porfolio. That’s End Games and it’ll be out February 5 of next year (2019). After that, next August (2019) will be the Mage Fire War, which is the third book about Beltur in the Recluce Saga. And then after that’ll be Quantum Shadows.

And all published by Tor.

Right. As a matter of fact, my first two books were published by other publishers, but all my books are now under Tor and have been for 30 some years.

You said you’ve only ever worked with two editors. It sounds like you’ve had good experience with your editors.

I can’t tell you how fortunate I am that Jen and I get along and she pretty much followed in a lot of ways the example set by David, but I also realized something rather amusing about the whole thing. Most people don’t know that David, although he’s been a fixture in science fiction for years, most people outside of the inside don’t realize that he also had a PhD in comparative medieval literature, and what’s interesting here is that Jen has a PhD in theater history. So, I may be one of the few novelists who’s been edited by academic PhDs who are also very strong on science fiction and fantasy.

I think it has made it a lot easier for me dealing with them, because I tend to…let’s put it this way: there is a lot of subterranean depth in what I write, and it’s helpful to have editors who can recognize it.