Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

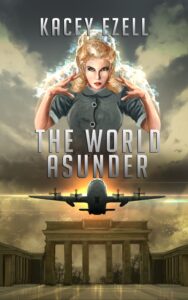

An hour-long conversation with Kacey Ezell, an active-duty USAF instructor helicopter pilot who writes sci-fi/fantasy/horror/noir/alternate history fiction including Minds of Men and The World Asunder, both Dragon Award Finalists for Best Alternate History in 2018 and 2019, respectively, and, with Griffin Barber, the far-future noir thriller Second Chance Angel.

Website

www.kaceyezell.net

Facebook

@KaceyEzell

Instagram

@KaceyEzell

The Introduction

Kacey Ezell is an active duty USAF instructor pilot with 2500+ hours in the UH-1N Huey and Mi-171 helicopters. When not teaching young pilots to beat the air into submission, she writes sci-fi/fantasy/horror/noir/alternate history fiction. Her novels Minds of Men and The World Asunder were both Dragon Award Finalists for Best Alternate History in 2018 and 2019, respectively. She’s contributed to multiple Baen anthologies and has twice been selected for inclusion in the Year’s Best Military and Adventure Science Fiction compilation. In 2018, her story “Family Over Blood” won the Year’s Best Military and Adventure Science Fiction Readers’ Choice Award.

In addition to writing for Baen Books and Blackstone Publishing, Kacey has published several novels and short stories with independent publisher Chris Kennedy Publishing. She is married with two daughters.

The (Lightly Edited) Transcript

So, Kacey, welcome to The Worldshapers.

Thank you so much for having me.

I should point out that we are speaking across a vast portion of the Earth’s surface, since you’re Tokyo, and I’m in Regina, Saskatchewan. So, yeah, 15 hours difference, I think. So, it’s an early-morning interview for you and a late-afternoon one for me, on two different days. It really is a science-fictional world.

The future is now, friends. It really is.

Exactly. Well, I’m glad to have the chance to talk to you. Your name was suggested to me by one of your fellow Baen authors. So, I’m always glad to get recommendations for people I’ve talked to. We’ve never met in person. So, this will be a good chance to get to know you. So, let’s start at the very beginning, as they say in The Sound of Music. And one interesting thing is that you were born in South Dakota, as you probably actually know where Saskatchewan is. So that’s nice.

I do vaguely. Sort of northish.

Yeah. Just go up past North Dakota, and then it’s us, basically.

Yeah, right.

So, yeah, so, let’s start with—I always say this—we’ll take you back into the mists of time, where you grew up and how you got interested in . . . well, probably you started as a reader. Most of us do. And how that led you to become a writer. And also, this whole bit of being in the Air Force and being a helicopter pilot. That’s interesting, too.

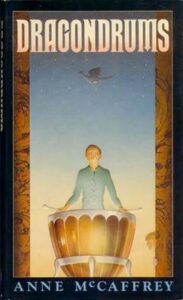

Well, yeah, so. So, I was born in South Dakota, but my parents, when I was about six years old, my parents joined the United States Air Force, as well. And so, we started moving around shortly after like first grade. And one of the very intelligent things that my mother did . . . so, I was kind of an early reader. I started reading just before kindergarten. And once I started reading, I very quickly devoured, you know, any written word I could get my hands on. And during one of our first moves, my mom, I think desperate for me to stop whining that I was bored and didn’t have any friends yet, because we had just moved, to put a copy of Anne McCaffery’s Dragondrums into my hands and said, “Here, this is for kids, read it.” And so, I read it and was immediately entranced. And that was my gateway drug to science fiction and fantasy, if you will, was the Harper Hall trilogy for Dragonriders of Pern.

That would do it.

Yeah, yeah, it really did. And, well, you know, and so here’s me, I’m like, well, so, I read Dragondrums when we lived in Albuquerque. And then very shortly after that, we moved overseas to the Philippines. And during that overseas move, my mom gave me the actual Dragonriders of Pern trilogy, the first trilogy that Anne McCaffrey wrote in that series. And for, you know, a kid who was leaving all of her friends behind to go overseas to another country, like, the idea of being a dragonrider and being telepathically paired with, like, your perfect companion who will always love you, who will never leave you, you’ll never have to move away from, was really enticing. And I got it into my head that I really, really wanted to be a dragonrider. And it turns out dragons are in fairly short supply here on mundane Earth. So, my very logical nine-year-old brain decided that I was going to be a pilot instead because that was about as close as I was going to be able to get. So that’s when I, one, both fell in love with science fiction and fantasy, and two, decided to pursue aviation as a career. It’s all Anne McCaffery’s fault.

Besides Anne McCaffery, were there some other books that were kind of inspiring to you along the way?

Oh, absolutely. You know, like I said, I, I read anything I could get my hands on, so, you know, my mom put The Lord of the Rings, she bought me that trilogy very shortly after that. And, you know, I got really into Tolkien for the, which was my introduction, as I think it is for most people, to the world of high fantasy. And, you know, in an odd way, you know, I pointed this out at a convention a couple of years ago, but there’s a connection there between, like, Tolkienesque fantasy and a lot of the military science fiction that, you know, that I read and write today because, you know, with epic fantasy, you’re talking about these sweeping movements, but you’re also a lot of times talking about armies and, you know, the movements of armies and the tactical decisions of the, you know, of their leadership and stuff. And that’s part of what makes military science fiction so interesting, too. So I think that that kind of, in a way, laid the groundwork for my interest in that, as did my, you know, my own military career, of course. And the experiences that I had growing up as a military brat, particularly living overseas in the Philippines, which was, you know, as I’m sure most people know, the Philippines was a hotly contested area back in the, you know, 1940s timeframe. And so, the opportunity to see a lot of those historical, you know, memorials and some of the battlefield sites and things of that nature was really cool and really interesting to me as a budding history enthusiast and writer.

Well, when did you actually start trying your own hand at writing?

So, my mom, somewhere in her stuff, has a notebook that I wrote, like, some of my first stories in, when I was about six years old. So, I was young. I started writing almost as soon as I started reading.

And did you . . .

Maybe that wasn’t the answer to the question that you wanted as far as, like, professionally, is that what you’re saying?

Well, how did that develop? And as you went along, I mean, OK, you started when you were six, but you wrote longer and longer stuff. And did you share it with other people? I like to ask that question because I did, but not everybody does.

Yeah. No, I did. I did. I shared it. You know, I would show my things to my mom. And my mother was . . . so, my mother’s a huge science fiction fantasy fan. She’s a, you know, she’s another voracious reader, and she’s always been, you know, probably my you know, my number one first reader and fan, obviously, you know, as moms tend to do so. Yeah, I would show me my stories to my mom. But the other thing that I would do and, you know, I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was kind of a bossy little girl. So when, you know, I would get my friends together, the kids together in the neighborhood or on the playground at school or wherever, a lot of times it was like, “Hey, let’s play pretend. We’re going to pretend that we’re on a spaceship and you’re going to be the captain and I’m going to be the pilot. And you’re going to . . .” And I would make up these play scenarios that really were just stories, you know, and I was like, “OK, and now the aliens are attacking.” And, you know, it’s, so . . .

So, I used to do that. My friends never really got into it the same way I did. It was kind of annoying.

No. Well, mine rarely did. Sometimes it worked, you know, and sometimes we would play out, you know, a certain, I don’t know, scenario for a couple of days or whatever. But, yeah, in in a lot of ways, I think that was . . . well, it wasn’t necessarily writing things down, but it was still sort of making up stories and sharing, you know, sharing those stories with other people, trying to involve other people in my stories, so. Yeah. A little bit of an extrovert, so yeah, I tend to want everyone to pay attention to me and my stories.

Well, you went into the Air Force and pilot training and all that. I would have thought that would keep you fairly busy for a while.

Absolutely.

When did you start to try to write professionally?

Well, so yeah. So, for sure, the Air Force kept me very busy. But here’s the thing, is that . . . so, I graduated in Air Force Academy in 2003, sorry, 1999. And right around that time I discovered the magical world of AOL fandom and the Dragonriders of Pern fandom groups that existed there. And so, once again, you know, Anne McCaffery comes to my rescue, right? So, even though I was busy at work and busy, you know, learning to fly and things like that, one of my hobby outlets became interacting with other fans on these groups and actually writing fan fiction.

And in those groups, you know, doing like . . . and when I say writing fan fiction, it wasn’t necessarily, like, writing stories to, you know, be produced in like a fanzine or anything like that. It was mostly, like, role play by email, essentially, where, you know, I would create a dragonrider character, and my friends would create this other one. And we would, our characters would, interact via the email. And it’s super geeky and super nerdy, I mean, don’t get me wrong, but it was an outlet, and it was something that I really enjoyed. And it allowed me to, you know, to kind of play in one of my favorite worlds. And so . . . and actually, you know, during the course of that, I learned a lot about, you know, things like character development and story pacing and, you know, what to do in dialogue, what not to do in dialogue, and how to keep your character’s thoughts confined to their own head and not go head-hopping and things like that, because you can’t act when someone else is controlling the other character in the scene, you know, it’s considered very rude.

So, yeah, super geeky, but it was fun, and it allowed me to continue . . . you know, Toni Weiskopf, the publisher of Baen Books, she has a saying that she says all the time, that writers write because they can’t help it. And I find that to be kind of true in my case, that if I’m not actually, like, writing stories, the stories are going to come out in some way, whether it’s through, you know, playing with my friends or doing online fan fiction or whatever. I’m never not writing, right? It’s kind of like breathing. It’s something that I have to do.

That sounds familiar. And you don’t have to talk to me about being geeky. I actually drew pictures for a Star Trek fanzine when I was in university. So I was . . .

Oh, that’s awesome, dude.

Doing pictures of Kirk and Spock. I think I did a pretty good Spock. And I’m not . . . that’s all I can remember. I remember doing a pretty good Spock.

That’s awesome. Yeah, I have zero talent when it comes to, like, creating visual fan art. I wish I did, because there’s some gorgeous stuff out there, and yeah, I would love to learn how to draw dragons, but . . . just never got there.

Well, I minored in art, so it actually was a potential direction to go in.

Oh, that’s cool.

But I . . . I often say that I supposedly majored in journalism because I wanted to be a writer, but really, I majored in Dungeons and Dragons and everything else was kind of a sideline to that.

Dungeons and Dragons should be a major at school.

Like, I think I put more time into that than I did my schoolwork, for sure.

Yeah. There’s a lot that you can learn from tabletop role-playing. I, I support that. Really.

So, when did you start trying to get published professionally?

So, I have a confession to make, but it happened sort of by accident. So, when I was in pilot training back in 2001, I discovered the amazing, mind-bending experience that is DragonCon in Atlanta over Labor Day week.

I’ve been once.

Oh, my gosh. Am I right, though? It’s mind-bending. It’s like walking into . . . it’s like being, you know, being away from home your whole life and then walking through the doors of the hotel and suddenly you’re on your home planet with your people. Everybody’s geeky, everybody’s into the things you’re into, and if they’re not, it’s just because they don’t know about it yet. And yeah, I love it. DragonCon is always the highlight of my year.

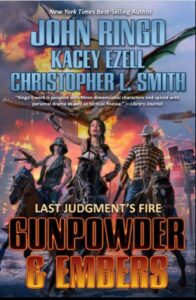

But my first one was in 2001, because I’m super-old, and after that, I went back several other times. And one of the . . . so in 2004, I think was the next one that I attended. And in 2004, I had the opportunity to meet a guy by the name of John Ringo, who—I didn’t know this at the time, I hadn’t read any of his work before meeting him—but he was a New York Times bestselling military science fiction author, also published by Bain Books, still is, as a matter of fact. And just talking with him, you know, he’s into MilSciFi, that’s his genre. And so, you know, we were talking about flying and about, you know, fandom and being geeks in the military and things like that. And he struck up a friendship with our group of friends that were, we were all there together, and we maintained an email correspondence. And I saw him at conventions, you know, a couple of years after that.

And then when I was deployed to Iraq in 2009, he emailed me and said, hey, I’m doing this, you know, I got asked to do this project, I’m editing this anthology of military science fiction by military veterans, and I want to include some new voices, along with some of the, you know, the reprints that we’ve done and things like that. And I know you just finished . . . so, the Air Force made me get a degree, a master’s degree, but they didn’t specify what it had to be, and so, I was like, all right, well, I’m going to get an MFA in writing, because screw you guys, I can do what I want. And so, John knew that I just finished that just, you know, because I had been like, hey, guess what, I’m done with my master’s. Right?

And he was like, “I know you just got your writing degree. Do you want to, do you have anything that you’d like to submit?” And I said, “No, but I could. Give me 24 hours.” And so, I wrote a story very quickly. But when you’re deployed, there’s very little to do. You really, like, you go to work, you fly, you go to the gym, you eat, and the rest of it is just kind of hanging-out time, right? And so, I just took that hanging-out time and knocked out this story. And it wasn’t very long. I think it was only, like, 5,000 words or something like that. But it was a cute little story. And I sent it in, and it became part of the anthology, you know, they accepted it for the anthology. And so, that was my first publication.

And then after that, Jim Minz, a couple of years later, once I was back in the States and again back at DragonCon, Jim Minz, you know, who also had, he was one of the editors on the product as well, came up to me and he was like, “So, when are you going have a novel for me? I’ve been waiting for it for a couple of years. And I was like, “Oh, well, let me get on that.” So, that was really the start of my career. I started doing, writing short stories for anthologies, again, mostly connected with John Ringo. He kind of like pulled me . . . and then I started, you know, branching out from there.

Before we go on to what you started writing at that point, I’m interested in the MFA because I’ve talked to other authors who have had, you know, that sort of formal creative writing training. And I get mixed reviews on how helpful it actually was. Was it helpful in your case? Did you find it very worthwhile?

So, aspects of it were helpful. Not necessarily from the standpoint of professional connections or anything like that, but like I said, the Air Force was going to make me get a master’s degree, and they were going to pay for it, and they didn’t really care what it was in. It was just kind of, almost like a box to be checked. So, I decided to do something, you know, knowing myself the way that I do, I really only want to spend energy and time on things that are interesting to me. And I knew that I wouldn’t, you know, if I tried to get, like, an aviation management degree, there would be aspects of it that were interesting, but there would be other aspects of it that would be deadly dull and that I would probably procrastinate and, you know, potentially not do very well. So instead, I chose to pursue the MFA in creative writing.

Where did you get that?

From National University. It’s a primarily online university that caters to a lot of military folks. I think they’re based out of San Diego. So not a real big, well-known name in academia or anything like that. But the program itself I really enjoyed. I found it to be . . . you know, because I think what I was trying to get out of it was one, just the piece of paper that said I had a master’s degree that the Air Force required, but two, I was just trying to have an enjoyable experience and kind of expand my toolbox, if you will. My concentration was in poetry, not in short fiction or . . . I mean, I guess you could kind of do a long fiction concentration . . . but I chose poetry, in part because I’ve always loved poetry. I’ve written it almost as long as I’ve written stories. And I find that a skillful . . . that a lot of the tips and techniques and, you know . . . what’s the word I’m looking for . . . just, the things that you do that make poetry poetry, can really inform your prose writing and really help to make it beautiful. So that’s why . . . well, and also poems are shorter. So again, less—typically. Not always. Sometimes they’re super long—but the graduation requirements were definitely shorter. Rather than writing a novel, I only had to write a book of 50 poems for me to complete my program. So that was a pretty big draw, too. You know, when you’re active-duty military and at the time a single mom, I was trying to balance out my requirements, and that was my strategic decision.

But I did. I loved it. Not because it necessarily got me anywhere in the publishing business, but for my own personal development. It taught me how to critique. It taught me how to take critique. And that’s probably the most immediately valuable lessons that I learned from that program, is how to how to give a constructive critique that is actually useful to the other individual and how to receive critique and to tell what’s constructive and what’s just, “Oh, I loved it. It’s great. You should write more,” you know, stuff like that. Not that there’s anything wrong with those kinds of comments. We love those kinds of comments, but they don’t necessarily help develop you as a writer.

Yeah, it’s like . . . my mom didn’t read my stuff, but my dad would, and he’d say it was great and, OK, but I need more than that to make it better in the future.

Right. Right.

Your poetry that you were writing, did it have any fantastical element to it, or was it more straightforward?

Some did, yeah, some did. So, what I what I mostly wrote for the program was actually aviation-related because I was the only pilot in my group that was going through the program at the time and so, you know, write what you know, right? But also, not only write what you know but write about what makes you different and what makes you unique. And that’s sort of, you know, find that niche, that brand. And so, I ended up writing a lot of poetry about, I’m just thinking of my chapbook collection now, you know, a lot of it has to do with flying and, you know, being in the air force and, you know, what it’s like to fly in the daytime and nighttime and stuff like that.

So, this has nothing to do with writing a book. What drew you to helicopters as opposed to, say, fixed-wing?

They were more fun.

They’re more fun?

They seemed more fun. Yeah, no, before I went to pilot training, when I was a what’s called a casual lieutenant, I had already graduated from the Air Force Academy and been commissioned, but I was awaiting my pilot-training start date. I had the opportunity to ride on an MH-53 helicopter. It’s what the Air Force used to use for special operations. They’ve since retired that airframe. And I remember sitting on the back . . . so, it had, like, a ramp on the back, and it had a 50-caliber machine gun mounted on that ramp. And we were out flying over a range. And I didn’t actually get to shoot that day, which made me very sad. But I did get to sit on the ramp next to the gunner. You know, he was sitting on one side of the weapon, and I was sitting on the other side and, you know, kicking my feet off the back of the ramp. While we’re flying 50 feet above the ground and it was pretty cool. I was like, yeah, this is a lot of fun. I want to do this.

Was it at least some of the feeling of flying on a dragon, do you think?

Oh, yeah, maybe. Maybe although, yeah, not necessarily that particular experience because we were going backward, you know, because I was sitting out the back. But sometimes, yeah, sometimes it has. You know, when you can feel . . . the thing about flying helicopters versus flying fixed-wing is that, you know, flying fixed-wing is about 50 percent art, 50 percent science, right? But flying helicopters is more like 70/30 art versus science. And the reason is because you do so much more of it, at least my helicopter. Now, I fly a UH-1 Huey, which, you know, was the quintessential Vietnam era helicopter, if that tells you anything. Every tail number that I fly was made in 1969. So, they are old birds, and we’re not talking cutting-edge technology in any sense of the word. And so, because of that, in part because of that, so much more, so much of what we do is, it’s our seat-of-the-pants muscle memory, like, you have to, it has to feel right.

And that, you know, when we’re teaching young aviators, half of what we’re teaching is just getting them to practice the maneuvers to the point where they can feel what feels right versus what feels wrong. And so, I think that when, you know, occasionally when you do a particular maneuver, and it feels just right, I think that it must be very similar to what that would feel like, you know, on the back of your own dragon to whom you were telepathically linked.

I’ve been sitting here trying to remember . . . I had characters in a helicopter in a book, two or three books ago in my current series. And so, I was researching helicopters because I’m not exactly an expert on the subject. And I went down a rabbit hole where I was reading helicopter jokes for about half an hour.

There’s a ton of them.

And unfortunately, I can’t remember any of them off the top of my head. I was going to try one on you, but . . .

Yeah, well, beating the air, we don’t fly, we beat the air into submission. That’s a very common one. Or, we don’t fly, we’re so ugly the Earth repels us.

Oh, yeah, I remember that. Yeah.

Oh, yeah. No, it’s there’s a, yeah, there’s a ton of helicopter jokes. And what’s so funny is that that, you know, like a lot of professions that, you know, have jokes about us, we tend to embrace those things. And helicopter aircrews as a whole, we have a reputation for being a little bit crazy. And what’s very interesting about that is that there’s some science to actually back that up. If you put our personality traits, and by our I mean society’s personality traits on a bell curve, helicopter aircrews are highly skewed to one end when it comes to traits of, like aggressiveness and, you know, adrenaline junkieness, whatever, whatever the proper term for that is. So, yeah, so there’s some data to back up the fact that we’re all crazy., Or you could just meet one of us and know that.

Well, taking us back to the writing side of things . . .

Sure.

So, Jim Minz had suggested a novel to you, but your . . . was your first novel Minds of Man? Is that then your first novel? But that’s not a Baen book.

Yeah, no, well, no, so . . . not for lack of trying. It wasn’t. So my first . . . my first actual novel contract was with Baen, and it was for Gunpowder and Embers, which was a collaboration that I did with John Ringo and Christopher L. Smith. And that just came out last January. And while we were working on Gunpowder, and it was . . . we’d finished up the first draft, and it was in edits and development. I had this other idea to write a story about World War II aviation, but with female psychics on board.

As one does.

Right. Well, because so what got me thinking about it was, you know, I was thinking about how aircrew are kind of a different, you know . . . like a lot of subcultures, I’ll say, you know, we end up being kind of a different breed and having our own discreet ways of communicating with one another. And I kind of got to thinking about that. And then the other thing that happened was that we had an air show and I had the opportunity to see the inside of a B17 cockpit. And I’m used to flying with a relatively primitive aircraft. But I got nothing on those guys, man. I have no idea how they even navigated. I mean, it’s no wonder that they had an entire crew member whose sole job was to do navigation, because their navigation, you know, their tools that they had to use were so primitive, and to think that they took hundred-ship formations of this incredibly primitive aircraft, not just into the weather, but into the weather, out the other side, and then flew them in combat. It was, like, mind-boggling. I mean, just the amount of courage of those men who did that was, you know, it was flabbergasting when it dawned on me the magnitude of the task that they had accomplished and done so over and over and over again. And, you know, their loss rates were just staggering.

And so, I started thinking about that. And the reason I came up with the psychics was that one of the things that that could potentially compensate for, you know, in a way that we have compensated with technology, would be, you know, the instantaneous communication that a telepathic connection might provide, because . . . So, anyway, I got to thinking about that, and I decided to write a story, and it became Minds of Men. And did actually send it to Toni at Baen. And she sent it back saying, you know, “This is not for us.” It’s not for, you know, “It’s not the kind of thing that I think our readership would snap up.” However, she sent me some very, very valuable critique. And I will be forever grateful to her for that time and attention that she took to actually provide that for me instead of just saying, no thanks. And so, I took it and applied the critique. And I had recently been approached by Chris Kennedy of Chris Kennedy Publishing to do a novel in his and Mark Wandrey’s military science fiction shared world called The Four Horsemen Universe. And so, I decided to just ring him up, I guess, and say, “Hey, you know, would you be interested in looking at this?” He said, “Yeah, send it on over.” And the thing about Chris is that he’s an aviator, too, right? So, I think I kind of spoke to my audience there with that one and but yeah, he loved it. And so, I published it under Chris Kennedy’s Theogony imprint and, yeah, that was kind of the start of the Psyche of War series.

Well, we’ll take a closer look at that one as an example of your creative process. I did want to mention that I also had an opportunity to tour the inside of a B17 when it came to our local airport a couple of years ago. And my experience there, which I never thought I would have, was that this horrendous thunderstorm blew in, and we were all kind of stuck out there on the tarmac. And I’m standing under the wing of an all-aluminum airplane while lightning is cracking around and the rain’s pouring down. And I’m thinking, “I’m not sure this is the best place we could be at this moment, but . . .I have video of it somewhere. My daughter was with me, and she was quite concerned. And I wasn’t terribly happy myself.

Oh, poor girl, yeah.

But the other thing I want to mention that navigation was that my wife’s grandfather, my grandfather in law, was a First World War navigator on a Handley Page bomber. These things had an 80-foot wingspan. They were enormous. But you talk about your primitive navigation, it was mostly . . . we actually have, we actually have his notebook from when he was at navigation school, and he was like one of the top-ranking students when he was in the navigation school in the Royal Air Force. But a lot of it went down to was, “Do you recognize that church steeple over there on the horizon?”

Right.

’Cause that’s the target, right?

Yeah, absolutely.

So, that was interesting.

Yeah. So, by the time World War Two had rolled around, they had very, very basic radio navigation available. But what they would do is, they would call on the radio to a station and get a ping and then the navigator would plot the information that they got from that ping and then just triangulate their position from there. And then, they used a lot of dead reckoning, which, you know, that’s just following, you know, flying this direction over the map for a given period of time should put us here if we maintain a constant speed. And yeah, it was just it was insane. I’ll take my GPS, thank you very much.

I always found the word “dead” in dead reckoning to be a little alarming.

It’s slightly ominous for sure, especially when we’re talking about dead reckoning into combat. Right.

So, you sort of talked about where the idea for Minds of Men came from, and you gave a hint of it. But do you want to give a bit more of a synopsis of it and then we’ll talk about it?

Yeah, so the synopsis of Minds of Men is, essentially, it’s 1943 and 8th Air Force bombers are flying out of England and they’re, you know, they’re just getting their lunch eaten by the Luftwaffe fighters because they didn’t have a long-range fighter escort that had the capability to take them all the way to their target and back. So, they were particularly vulnerable during, you know, during part of their sortie. And their loss rates were just incredible and staggering, if you actually go and read those numbers and think about, you know, how many men that represents. And in this, like I said, in this world, some women—and they’re all women because I’m sorry, I’m sexist—but some women have the ability to create psychic connections with other people and communicate with them telepathically. And one of these Air Force generals knows about it because his wife is one of these women. So they end up, you know, doing a super-secret recruiting drive, essentially, and come up with 20 women powerful enough to do this job, who end up flying with these bomber crews out of England, helping them to maintain closer formation, better formation integrity, helping them to respond quicker to, you know, threats and things like that. And that ups their success rate, but at what kind of cost, right? Because now, these women are not only experiencing the hell of warfare for themselves, but they’re experiencing it tenfold because they’re experiencing it through the minds of each of their crew members, too. And then, of course, as is every aircrew member’s nightmare, you know, at some point the main character gets shot down. And so now, she’s stuck in occupied Europe, you know, with her surviving crew, trying to find her surviving crew members from the crash. And they’re having to escape and evade their way through occupied Europe, all while being chased by . . . because it turns out that the Germans have psychics, too. So, there’s a team of German Fallschirmjäger and a psychic woman who is pursuing them.

The latter half of the book was actually a lot of fun to write. Well, the whole thing was pretty fun to write, but I really enjoyed doing the research for the latter half of the book because I really got to dig into some of the stories about resistance-led escape lines that ran throughout Europe in the Second World War. And these were organizations that would help, not just allied airmen, but they actually started, really, helping to repatriate soldiers stranded by the evacuation of Europe, you know, ones who couldn’t get out at Dunkirk, essentially. At least, that’s when one of the Belgian lines that I researched started. And they would smuggle these, you know, these allied airmen and soldiers through the Nazi lines and, you know, take them on trains and try to get them out, either get them out to sea to get picked up by, usually, Royal Navy destroyers, or over the Pyrenees into ostensibly neutral Spain and get them picked up at the British embassy there. So really fascinating stuff and it was a lot of fun to right, you know, to kind of combine those stories and put it in my own.

Well, so, what . . . that kind of brings you out to the next question. Well, first of all, you said, you know, as a helicopter pilot, you’re kind of a seat of the pants flyer. Are you also a seat of the pants writer, or are you a detailed outliner?

So, that aspect of my style is sort of evolving, honestly. And I do a lot of collaboration, and I find that when working with another author, a detailed outline is actually really helpful because it allows you to say, “OK, well, you know, I’m going to go away, and I’m going to work on this part of the outline. I’m going to bring it back. And here it is.” And then, you know, you can just get more done that way if you agree ahead of time where you’re going with the story. So, you don’t have surprises. For myself, I would say that I’m an outliner, but I outline in phases. I don’t do the whole thing right up front, all right, like the outline of the first act and then I’ll write the first act and kind of see how it’s going, and then I’ll figure out, “OK, where am I going to go in the second act?” And so, I kind of do it in chunks, if that makes sense.

And once you have the outline, what is your actual writing process. Do you write, you know, with a quill pen under a tree or . . .

No, I use my laptop.

Well, being a poet, you ever know.

Right? Yeah. No, I, I use my laptop. I actually, I enjoy Scrivner. It’s a program . . .

Yeah. I have it, and haven’t climbed the learning curve yet to use it, but I have it.

It is steep, the learning curve is steep. I got it. And I went ahead and said, “OK, you know, I paid for this program, I’m going to learn how to use it.” And I dedicated two days and just went through the tutorials. And it took that long, but I’m glad that I did it because, you know, it walked me through all of the functionality. And I’ve since forgotten a lot of it because I don’t, you know, it’s a very, very capable program. And I don’t use, you know, I probably only use about two-thirds of what it’s actually able to do. But, yeah, I like it a lot. I like the flexibility that it gives me to move things around and kind of see, “OK, this is where this is,” and, you know, link characters to different things and stuff. So. Yeah. I use Scrivener.

Do you write sequentially.

Yeah, most of the time I have to. When I don’t, it’s usually because I’m dead stuck, and I’ve just, I’ve got to skip a part and go on and come back and fill it in. But for the most part, I write sequentially. The challenge for me is always, like I think it is for many people, you know, who have day jobs and families and stuff, is always finding that balance to, you know, time to dedicate to sit down and do the writing. And not just the time, but the energy, you know, because I could for sure sit down every night at 10:00 and write for an hour, but by that time, a lot of times I’m so exhausted that, you know, what would be the point, right? I don’t know that I’d get anything useful out of it.

Yeah, it does take energy to write. I’m not . . . you know, people think you just sit there and type, but it actually takes a lot of energy to write.

Right. Right. And it’s the mental energy, which is the kind that, like, just gets sucked out of you if you have a boring day at work or whatever. So, for me, what I’ve found is that I have to have a very low but consistent daily word-count goal. And I have to keep that habit up of writing. So, mine, it’s . . . I don’t even know if it’s the goal, but my minimum is that every day, no matter how exhausted I am, I need to sit down and write 100 words, just 100 words. And if I get to 100 words, and I’m exhausted, and I want to quit, I’ll allow myself to quit and just say, “OK, this was a lower day.” But just like with . . . and I actually heard of this technique in regards to exercise, actually, where people are like, “Oh, I don’t really want to go to exercise, but let me, you know, let me get on the bike for ten minutes. And after ten minutes, if I want to quit, I let myself quit.” But most of the time, you know, by the time you’re 10 minutes in or, in the case of writing, by the time you’re a hundred words in, you know, there’s more going on in your head, and there’s more that’s ready to come out. And so, you end up getting a little bit more than that, at least.

So, my productivity has definitely fallen off this year. Like, you know, I think a lot of us who write, that’s been the case. At least, you know, among people that I’ve talked to, that’s been the case. And using this technique of forgiving myself and just being like, all right, you know, I’m going to keep, as long as I’m moving forward, forward progress is forward progress. We’re not going to harp on how much forward progress we’re getting. It’s been working for me.

Once you have a draft, what does your revision process look like?

So, I do the thing that most people say you shouldn’t do, and I edit as I go, but I do that because I, I can’t . . . it just bothers me. It bothers me to not do it. So, I do, I edit as I go. So, once I have a draft, it’s usually fairly clean. I will read through it one more time out loud because I find that that helps me catch typos, and more importantly, it helps me catch repeated words that I, you know, use too often.

Yeah, reading out loud is a great way to find things. Better to find it while you’re writing it than when you’re doing a public reading later, which is when I usually find those things. Oh, I wish I’d change that before it went into print.

That’s not what I said. Yeah. And that was another tip from Toni Weiskopf from Baen Books. So, it was read it out loud and listen to, you know, listen to how it flows and how it sounds and stuff. So, I will I’ll read through the draft out loud, start to finish, and make any changes that I, you know, that I find needs making there. And then from there, I usually send it off to the editor and let the editor, you know, take a look.

So, you don’t have any beta readers or anything like that?

Well, no, that’s not true, I do. It depends on the project, right? So . . . and again, a lot of times, you know, other than the Psyche of War series, a lot of my novels have been collaborations. So, you know, a lot of times I will bounce the ideas or . . . not the ideas, but I’ll go through it, and then my co-author will go through it, is what I’m trying to say. And sometimes, we have beta readers. But sometimes, you know, like I said, it just goes straight to the editor. A lot of times lately, we’ve been working very under, very, you know, right up to the deadlines. So, not the best practice, but . . .

But it’s an extremely common one. Let me tell you.

For Gunpowder, we had beta readers, for Second Chance Angel, we had beta readers. So, I had some beta readers for Minds of Men. I didn’t for World Asunder because I was late on it. So, it was like, all right, get it done, make sure it’s clean, send it to the editor.

What kind of editorial feedback do you get back typically?

Oh, again, you know, it varies. For Second Chance Angel, Griffin and I had the wonderful experience of working with . . . oh, I’m going to not remember her last name . . . our editor, Betsy. She’s a fantastic editor who’s been in the business for years and years. And she worked with us on a developmental level. And so, with her, you know, we sent her the draft, and she came back, and it was it was very much a conversation kind of . . . modality, I guess. You know, where it was like, all right, so, you know, “I have questions about this. What if you did this to this part?” or “What would you think about this?” or “This part threw me out, you know, of the story.” “How can you make this . . . how can you tie this back in?” And she had some . . . you know, one of the major, one of the best suggestions she gave us was, you know, Second Chance Angel is a post-war, post-galactic-war story. And Betsy, she came back, and she said, “Look, I think that what you really need to do is make a timeline of the war so that you have it very clear on how all of these things, you know, kind of came to be. It doesn’t necessarily have to be included in the text, but you guys need to know it,” and, you know, things like that. On the developmental level, some of my work, when I get edits back, it’s really just, like, copyedit-level stuff. And I find that, I get that. So, with my Psyche of War series, because it’s alternate history, I don’t have to do a lot of worldbuilding because it’s our world, there’s just psychics in it, right? So, I find that the more—maybe I’m just weak in worldbuilding—the more worldbuilding I have to do, the more, like, developmental-edit type feedback I get, whereas when there’s not that much worldbuilding to do, it’s really more on the copyeditor level, if that makes sense. And I’m happy to have it both.

You’re talking a little bit about Second Chance Angel, and that’s the other one we want to mention. I’m actually talking to your co-author, Griffin . . .

Yes.

. . . actually, this week, as we’re speaking, in just a few days, I’ll be talking to him, too. So, maybe . . .

He’s a riot. You’re going to have a good time.

Maybe a quick synopsis of that one, and then we’ll talk about it a little bit.

OK, so, Second Chance Angel is a sci-fi noir thriller that Griffin Barber and I co-wrote together, and it is the story, like I said, it’s a story set in the aftermath of a great galactic war, where humans essentially joined this war on the side of this alien race, kind of mysterious alien race, that we call the Mentors. And one of ways that the Mentors enticed humanity to come into the war on their side was by offering these cybernetic upgrades that require artificial intelligence to run the upgrades or to maintain the modifications. And so, these . . . they have these AIs that were written as personal AIs that inhabit the body with the person. And it should kind of just be transparent. But one of our characters is actually one of these AIs that we call angels. And so Ralston Muck is a down-on-his-uck veteran bouncer who’s had his angel removed . . .

That’s a great name, by the way, Ralston Muck.

Yeah, that was Griffin’s idea. It’s very noir.

Very.

So, he finds himself, you know, mixed up in, and went, you know, when a singer at the club that he works at disappears and he finds himself in a position of having to go look for her and having to work with her personal AI to go find her. You know, they kind of slip into, uncover some seedy underworld stuff, as you know, as noir stories do. And, yeah, so that’s sort of the synopsis of the book is that they’re trying to find Siren . . .

Oddly enough, I just watched Chinatown last night. You know, it’s only been out for, what, 50 years and I’ve never watched it, so . . .

Well, it’s such a great movie. Yeah, it’s . . . I love the noir subgenre and Second Chance Angel for both Griffin and I is sort of our love letter, too, to the noir subgenre. A couple of years back, when I really got into it, I was reading a lot of Raymond Chandler, and I just I fell in love with the way that that guy could turn a phrase, you know, and the way that he would create these characters and make them, you know, just real people, just by the words that they would say and the comparisons that they would draw, you know. And so, yeah, I, I love it. I love the aesthetics of it. And so does Griffin. And so, we decided to write a book and make it noir.

And how did you do that? Did you write, like, one chapter, alternating chapters, or exactly how did that work?

Kind of, yeah. So, in the book, we have essentially three points of view represented. So, one of the noir tropes is that, you know, you have this first-person point of view narration, which has its advantages and it has its disadvantages. One of the advantages is that you can really do some cool, like, unreliable-narrator type stuff that way, right? And we did do some of that. But one of the disadvantages is that it’s by necessity a very tight POV. You know, there’s only so much that you can do. So, what we did was, we had both Angel and Muck in first person POV, and I essentially wrote Angel’s Point of View, and Griffin wrote Muck. And there was some overlap. And sometimes where we, you know, did one or the other. But for the most part, that’s how it came about. And then, kind of to address that that disadvantage, you know, we realized that there was another dimension to the story that we needed to tell. And so, we did that through some of the additional AIs that are not necessarily personal augmentation eyes like Angel, but, like, the AI that is running the admin for the space station and the AI that is the law enforcement officer AI. We rolled them in and used them to tell part of the story, too, from a third-person point-of-view perspective.

Well, it sounds quite fascinating.

Yeah, it was fun. It was . . . it kind of came about organically, you know, we didn’t sit down and say, “OK, you’re going to do this, and you’re going to do this.” It was just sort of like, “Well, here, let me see. Well, I think this is how Angel would react,” and was like, “Oh, OK, well, this is what Mike would do next and just sort of went from there.”

Well, getting close to the end of the time here. So, time to turn my attention to the big philosophical question, which is . . .

Dum dum dum.

Yeah, exactly. Why, why? Why do this? Why write? Why do you write? Why do you think anybody writes? Why do we tell stories, and why specifically stories of science fiction and fantasy?

Oh, OK, well, those are a lot of questions.

I like to pretend it’s just one, but it’s actually more than one.

Yeah, really. So, the reason that I write? I write like I breathe, right? You know, I kind of alluded to this earlier when I was talking about being a little kid, and I’ve never not made up stories. I don’t know how to process life without making up stories. And I think that that’s on some level true for us as a human race. We are in so many ways defined by our stories, the stories that we tell, the stories that we remember, what we choose to remember, what we choose to forget. I think that stories are an essential part of the human experience. And because, you know, I don’t know you and you don’t know me, but I can tell you a story that is similar to something that you’ve experienced and that then becomes a point of connection between us. And I think that that’s something that was very important for us as humans to do, is to connect with one another, you know. So, I think that we write for all of those reasons, you know, because that’s part of what makes us who we are.

Why stories of the fantastic?

Because that also makes this part of who we are. Because we, you know, we have the amazing ability to not just talk about what is but what could be, and to get excited about what could be and to inspire ourselves and each other and. And so, I think that, you know, there’s great joy to be had there, in telling stories of the fantastic, whether it be in science fiction or in fantasy or even in, you know, even in the darker stuff, like the horror and the noir and . . .you know, they’re two very different things, but they’re all ways of processing this experience, right, so . . . you know, it’s like dark humor, for example. I mean, I’ve been in the military for 20 years, and I have a very dark sense of humor, and most of my friends have a very dark sense of humor. And, you know, the same is true of first responders who work where they see terrible things all the time, police officers who have to deal with domestic violence and social workers who have to go into these situations and stuff. One of the major coping mechanisms for all of this is dark humor, is the ability to laugh so that you don’t cry.

And I think that, you know, there’s so much out there that frightens us as humans, even, you know, even, you want to talk even on an evolutionary level, like, we’re not the biggest, baddest animal out there. We don’t have super-sharp teeth or super-sharp claws we can’t see in the dark. But what we do have is our mind and our imagination. And we have this, like I said, this ability to tell stories and this ability to inspire each other and this ability to think beyond what is, to see what could be. And that is our great evolutionary advantage. And so, you know, even taking something that’s dark and turning it into our own story, you know, telling a story about it, makes it a little bit more accessible, and it gives us the ability to process the emotions that come with fear a little bit better, in fact. I don’t know if any of that made sense.

It made sense to me.

OK, good. I’m glad.

What are you working on now?

So, Griffin and I are . . . we have started the sequel to Second Chance Angel, which . . . Second Chance Angel releases, if you don’t mind me saying this, Angel releases on September 8, which is today for me while we’re recording this, I’m not sure when this will go up, but here in Japan, it’s already release day. So, yeah, happy release day!

It will have been out for some time before this goes live.

Good. You guys can just be part of my retroactive celebration! So, we’ve started the sequel, which is called The Third Sin, and we’re about three chapters into that. I’m also working on the third book in my Psyche of War series, which is a story set in the Vietnam era. And I’m working on a sequel to Gunpowder and Embers, started outlining that, and a couple of short stories and stuff. So, I’ve got a lot of projects.

And where can people find you online? I mentioned the website off the top. Oh, I should say that’s . . . better spell that.

Yeah. So, my website kaceyezell.net. That’s sort of the hub for where you can find me. You can go there and find lists of all my books, all my social media links, and join my mailing list, actually. And if you do that, you get, like, two free stories. So, there’s that as well, if you’re into that sort of thing. But also, I’m available on Instagram at KaceyEzell and then Facebook at KaceyEzell, too. So that’s kind of usually where I’m most interactive on social media is Instagram and Facebook.

OK, great. Well, thanks so much for being on The Worldshapers. I enjoyed that. I hope you did, too.

I did! Thank you so much for having me. It was really fun to talk to you.