Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

An hour-and-twenty-minute interview with Patricia C. Wrede, award-winning author of more than twenty-two fantasy novels for readers of all ages, as well as two collections of short stories and one book on writing.

Website

pcwrede.com

Twitter

@PatriciaCWrede

Facebook

@PatriciaWredeAuthor

Patricia C. Wrede’s Amazon Page

Patricia will be instructing the workshop “Worldbuilding in Fantasy and Science Fiction” for Odyssey Writing Workshops in January and February. Register here by December 7, 2020.

The Introduction

Patricia Collins Wrede was born March 27, 1953, in Chicago. She and her siblings (she is the eldest of five) grew up in the Chicago suburbs. She attended Carleton College, where she earned an A.B. in Biology and took no English or writing courses at all. Following graduation, she earned a Masters in Business Administration from the University of Minnesota and worked for a number of years as a financial analyst and accountant. She married James Wrede in 1976; they divorced in 1991. She currently lives in Minneapolis with her cat, Karma.

She began writing fiction in seventh grade and continued off and on throughout high school and college. In 1974, she started work on Shadow Magic, which took her four and a half years to complete and another year and a half to sell. By the time the book was released in 1982, she had completed two more novels. In 1985, she left her day job to write full-time and has been making her living as a writer ever since.

To date, Patricia has published twenty-two novels, two collections of short stories, and one book on writing. Her work is available in twelve languages (including English) and has won a number of awards.

The (Lightly Edited) Transcript

So, Patricia, welcome to The Worldshapers.

Thank you very much. It’s an honor to be here.

Well, it’s great to have you. I don’t believe we’ve ever crossed paths at conventions or anything. But the folks at Odyssey reached out to me and suggested you’d be a great one to talk to. And I certainly agreed with that. And we are going to talk about the workshop you have coming up with Odyssey later on. But I’ll start the way I always start, which is by taking you back into the mists of time to find out how you got started (probably you started as a reader—from what I’ve read of your interviews, that’s definitely the way you started)-and how you then became interested in writing and fantasy and in science-fiction-type stories in particular. So how did that all . . .and where you grew up and all that stuff. So, how did that all come about for you?

Well, I grew up with parents who adored reading. I shocked some of my college friends when I told them that the only room in the house that I grew up in . . . I grew up in a big house because we had, my folks had, five kids, so I had four siblings, and we were parceled out. And so, it was a pretty big house. The only room in the house that did not have books in it was the dining room. And the only reason it didn’t have books in it was because there was, like, one wall of glass windows and another wall of windows and an archway door, and then you had to put the whichajigger, the sideboard for the dishes, somewhere, and that took up the last wall, and so there was no wall to put bookcases on. That was the only reason there were no books in the dining room. Officially. There were always books lying around, but they weren’t there . . . they didn’t have a home. But we had books in the kitchen, we had books in the bathrooms, we had books in the linen closet, and we had books in the upstairs hallway. The entire hallway was lined with books along one side. So, I mean, this is where I grew up and the way I grew up. And I was always, I loved reading, when I was five and started going to school, I was so excited about—I remember this, this is one of my very earliest memories—I was so excited about learning to read, I went off to school on the first day, and I came home, and I sat my brother and sister down in the backyard in the sandbox and told them I was going to teach them how to read. I was five, my sister was three, and my brother was two. This did not go well, but that’s how excited I was that, you know, everybody should know how to read as soon as they possibly could. And it just never occurred to me that, you know, two is possibly a little young, especially when you couldn’t really talk clearly.

And you grew up in Chicago, right?

I grew up in Chicago, in the Chicago suburbs. And I started writing my first novel, my very first unfinished novel, when I was in seventh grade. And it was the only thing I’ve written that isn’t technically fantasy, although it probably would have been if I’d gotten more than seven chapters. It was a kids’ wish-fulfillment adventure kind of thing. You know, they just moved into a new house, and he discovers a secret passage, and . . .

As one does.

Yes, as one does, every time you move into a new house, there’s a secret passage and secret rooms, and, you know, all kinds of fun things. And they were just heading into having discovered the secret passage that used to belong to the pirates that led to the castle. How they had a castle and pirates in, like, the middle of the Midwest in America, I have no idea. But I was in seventh grade. I, you know . . . who cared? Plausibility was not my thing. I suppose that makes it fantasy right there.

Of all the books that were lying around, were there some that were particularly influential on you in those reading years?

I read everything, and probably what I loved the most was fairy tales. I went through the entire Andrew Lang fairy tale collection. When I was in seventh grade, my beloved aunt in Alaska sent me a copy of Beowulf as a birthday present, and my parents gave me Bullfinch’s Mythology. And it was . . . I loved mythology and, you know, all of those sorts of stories, the fantasy. Older fantasies, you know, and fairy tales were what I could get my hands on, but this was really before fantasy was its own genre. You really had to hunt to find anything that was fantasy. It wasn’t until I got to high school that Lord of the Rings hit big in the United States, and suddenly you started being able to get fantasy. But there still was just not enough of it.

Yeah, I remember that. I’m a little just a little bit younger than you, I think. I was born in ’59, and I remember that. I remember as a kid, you know, you just couldn’t find the stuff. If you found something that was really fantastical, it was a rare treat. There was more science fiction, I think, but the actual fantasy stuff . . .

There was a lot more science fiction. So in high school, I mean, I read all the fantasy I could get my hands on, but most of what I read was science fiction because that was what there was. It was also what my dad read, and so I didn’t have to buy it myself. I could, you know, I mean, I only had so much allowance, and books were cheaper, but they were still expensive when you were in seventh grade. But I, you know, I got books for my birthdays. I had, you know, the Oz books. If you wanted something that’s influential, those and the Narnia chronicles were probably the first. I have almost the complete set of Oz books. I’m still missing two or three of the Ruth Plumley Thompson volumes, but I have the others, and I loved those. Probably my other big influences were The Man from Uncle and Rocky and Bullwinkle.

I remember those, too.

I’m absolutely sure those were important influences. And I get in trouble with English teachers every time I say that because they’re just not respectable. But, you know, when I grew up, fantasy wasn’t respectable either.

When you started writing, like, that first unfinished book when you were seven, did you share it? I always ask this question because some people did, and some people didn’t. I did when I was writing stuff as a teenager and so forth, and it kind of helped me know I wanted to write because people actually enjoyed what I wrote. Did you have people who are reading the stories you were writing in those early years?

Only my mother. And she was probably the other huge influence because there I was in seventh grade, and I told her I was writing this story, and she said, “Really?” And I showed her the pages, and she took them away, and she typed them up on her typewriter in proper manuscript format. Because she also wrote. I never was allowed to read her stuff because she wrote for the confessions magazines.

Oh.

And that was just not something that you . . . by modern standards, they’re extremely tame, but at the time, that was something you just didn’t even admit to, to your children. She didn’t even save any of her stuff when she passed away. The only thing she had kept was a manuscript for a children’s book based on the Mother Goose fairy tales, or rhymes, Mother Goose rhymes, that she had finished. She didn’t save any of her less-respectable stuff, but she wrote for the confession magazines for a while, for a couple of years, so she knew proper manuscript format, and she typed it all up for me. And I just thought it looked so professional. And she didn’t say a word about the fact that I must have written it during my classes because, you know, that was the only time that I could have produced this much. But she didn’t say a word. She just typed it all up and gave it back to me. And I got seven chapters before life happened, and I moved on to other things.

My mom was a prolific letter writer, but she was also a secretary, and she had an IBM Selectric at home, and she typed up my first short story in proper format.

Yes.

And that really made me feel very professional. I was about the same age.

Yes.

It was called “Kastra Glazz: Hypership Test Pilot,” was my first complete short story, so . . .

Ah-ha! Yes. I didn’t have a title for mine. It was only seven chapters, and it was never finished, but it was a novel. The first thing I tried to write is a novel. And then I had a couple of, I guess you’d call them articles, they were humorous stuff, in the high school magazine that they had. I did do a couple of things, but they were all non-fictional kind of humorous high-school slice-of-life things. And in college, I didn’t really have a lot of time to write. What I produced in college, somewhere along in between high school and the end of college, I got the notion that the proper way to write was to start with short stories and learn your craft. And then, when you had finally gotten good enough, you would write a novel. And so, I created this life plan. And I also got the . . . it had never occurred to me that you could actually make a living writing. And so, I created this plan for myself, a life plan. I was going to write and, you know, really work on my short stories from time to time as kind of a hobby for the next 15, 20 years. And when I hit . . . that would give me enough time to get really good at it and start selling my short stories and have a real track record here so that when I hit 40 and had my midlife crisis, I could quit my day job and write a book and still have something for an income. I was very practical about this.

It didn’t work out quite the way I expected. You know, I did write quite a few short stories. It turns out I’m not really a short story writer; I’m a novelist. And I kept writing them and sending them out, and I did get better. And after a while, they started coming back with notes on them from the editor saying things like, “This sounds like Chapter 3 of a novel, and this sounds like the plot outline for a novel.” And you’d think I would have bought a clue at that point, but I didn’t. I kept writing short stories and having them rejected. And finally, I had an idea for something that I knew was not a short story. It was a novel. And I wasn’t at the point where I was supposed to . . . my plan said that I was supposed to sell a bunch of short stories first, but I really wanted to write it. And so, I said, “All right, fine, I’ll write it, and I will stick it in the bottom drawer because . . . I won’t tell anybody. I just won’t tell anybody that I cheated and did the novel now. So, I did write it. It took me a long time because I wasn’t really paying that much . . . I wasn’t really focused on it. I was still trying to write short stories. And when I eventually finished it, it was sort of like, “Well, I could put it in the drawer.” But by this time, I had internalized the idea that when you finish something, you sent it out because editors do not do house-to-house searches for manuscripts. You have to put it on their desk. And so, I went, “Well, it’s done. What the heck?” So, I started, I put it in the mail, and it got rejected from the first place, with a lovely encouraging rejection letter from Lester Del Ray. And then, you know, I sent it to a couple of other places, and it got rejected. And finally, I sent it to Ace Books, and they accepted it, and they bought it. And, I was like, “Well, hey, cool.” And I never looked back from there. And that was Shadow Magic.

All those years that you were writing short stories and so forth, you’d actually studied biology, and then you got your MBA . . .

Yes.

. . . were you taking any formal writing, training of any sort? Did you ever do that during those years?

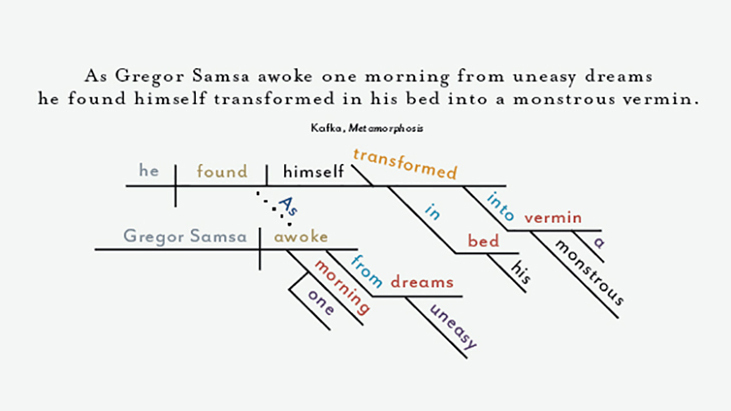

Nope. Nope, none at all. I had . . . I took no English classes at all in college. The high grammar school and high school that I went to both had excellent English programs in terms of the fundamentals. I mean, diagramming sentences. Remember, diagramming sentences?

My dad taught English, and he was big on that.

Nobody does that anymore. But diagramming sentences, that was a big thing. And so, I had a pretty good grasp of grammar and essay-writing structure and that sort of thing. But I, you know, once I passed high school, when I got to college, my philosophy was, I looked at the course requirements, I skipped out of the required . . . they required, like, the basic essay-writing class, and my AP exams were enough to let me skip that . . . and I looked at the classes, and I went, “OK, all of these English classes are about reading books. I know how to read books.” But the other things in that particular distribution requirement were things like history and art and, you know, those kinds of things. And I went, “You know, OK, I’m going to take stuff that I wouldn’t do by myself because I wouldn’t know where to start or I don’t know anything about it, and I want a little more guidance.” So, I took Art of the Far East, and I took History of India, and I took classes in subjects that I would not have explored or would have had a much harder time exploring on my own. And I did indeed, you know, read a lot of Shakespeare and other stuff. But no, I did not take any . . . Carlton didn’t offer creative writing, you know, formal creative writing. They may have had, like, one English class in it, but most of the English classes were more traditional English literature, study of English literature. And I figured I could read that on my own. So I did. And never, ever did take any creative writing classes.

And all of those other things you studied, have they fed into your writing over the years?

Oh, yeah. Everything always feeds into your writing. And, you know, people ask about sources, and really, writing, it’s kind of like making stone soup. You know, that folktale?

Yeah.

For listeners who might not, it’s a folk tale about a guy in the middle of the plague years who comes to a town, is begging, and they say we aren’t going to, you know, we have nothing. And he says, “Well, that’s fine. You’ve got a big pot. I can make stone soup for everybody.” And so, they give him a big pot, and he puts a stone in and a whole lot of water in and lights a fire under it and starts making soup and tastes it after a while and says, “Coming along great, but you know, some onions would be just the treat.” So somebody goes and gets some onions, and they put the onions in the pot. And then, a little while later, he checks it again. He said, “Yeah, yeah, I could use . . . a few carrots would be great.” And he keeps this up with each of the possible ingredients, and the villagers keep bringing him stuff. And finally, it’s all done, and it’s great soup, and everybody has some, and they just marvel at the fact that he made it out of nothing but a stone and some water. And writing is a lot like that. You know, people say, “Oh, you made it up all out of your head,” and it doesn’t occur to them that your head has had, you know, 20, 30, 40, 50 years’ worth of inputs of, you know, everything in the world, you know, from, you know, going fishing, going on a fishing trip to, you know, playing hopscotch in grade school, to everything you’ve ever read. You know, all writing is based on the writer’s life and in some sense or degree.

I often say when I’m teaching, writing, or talking to writers, the only person you really know well is yourself, and all your characters are going to some extent draw on what you know about yourself and what you’ve observed from the people around you. So, yeah, it’s al kind of, you know . . . “filling the tank” is the expression that sometimes used.

Yeah.

You didn’t take any formal writing courses, but you were a member of a writer’s workshop. And I often get asked about writers workshops . . .

A critique group.

A critique group. “Extremely productive,” it says in your bio here.

So, that would be the Scribblies. And that was a group that . . . originally I think it was six of us formed it and we added a seventh, one of our members moved out of town, and we wanted to stay six, and so we added a seventh and then she came back to town and so we just stayed at seven until everybody kind of went off in their own directions. But yeah, that was me, Steve Brust, Kara Dalkey, Nate Bucklin, Pamela Dean, Will Shetterly, and Emma Bull.

Pretty good collection of names there.

Yeah. Well, at the time, none of us was published, you know, we were all beginners. Will and Emma were, I think, the only ones who had taken a creative writing class, and Pamela had a Master’s in English, so she was our grammar maven. But it turned out to be a really great balance of people because everybody was really, really good at a different thing. And so, when you gave them a piece of writing to critique, everybody would spot something different, and the people who spotted it . . . you know, Pamela was really great at doing characters and dialogue, and when she said there was something wrong with the dialogue, there was something wrong with the dialogue. There were different people who had sort of different areas of expertise. It all flowed together really well, and it was enormously helpful. And critiquing other people’s stuff was almost more useful than having my own stuff critiqued. You know, your own stuff . . . when people give you advice about your own stuff, the tendency is to think in the back of your head, “What? You don’t know anything about that. That’s perfectly all right. That’s fine.” But when you see some other person’s stuff getting torn apart into tiny, tiny little pieces, you think to yourself, “Well, I’d better check and make sure I’m not doing that because I don’t want them to do that to me.” Tat’s really useful. It’s a really useful reaction. So, yeah, the right crit group can be—it can be, sometimes they’re destructive, but you just have to be aware of that, and it’s a matter of picking the right people and the people who are destructive in a constructive way, if that makes any sense.

Creative destruction.

Something like that. People are not afraid to point out your mistakes, but who don’t make you feel like you can’t correct them or that you’re smaller because you made the mistakes. You know, you don’t need people who are showing off how great they are; you need people who are trying to make your story better, honestly and truly, and that you can help them make their story better. That’s the, I think to me, the ultimate thing in a critique group. Now, you had another question?

I was going to say you’ve done quite a bit of teaching as well over the years.

Mm-hmm. Yeah.

And I have found, like, I just finished a term as writer-in-residence at the Saskatoon Public Library, and I was at the Regina Public Library a few years ago doing the same thing. And I always find that looking at other people’s, sort of like what you’re just talking about, looking at students’ work or other writers’ work and trying to help them with it is very helpful to mine, as well. Do you find that, you know, by . . . what’s the line from The King and I, “If you become a teacher, by your students you’ll be taught”? Do you find that to be true?

Yeah. Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. It’s one of the most rewarding things to do, but it’s also really fun to see, just to see what other people come up with because one of the things about writing is everybody’s process is different. And after doing this for 35, 40 years, the one thing I’ve discovered is that every book, the process is different. You know, there’s something that I think of as my normal process, but I think that only works on about 50 percent of the books I write. The other ones just go off on their own. They do their own thing. And you can’t predict which ones are going to be like that and which ones aren’t. They just . . . it’s how it happens and watching what other people do just . . . it fascinates me, all the different ways that people work and, you know, how they take an idea and something that I thought was very straightforward and pointing to the left and this is exactly where this is going to go, and no, it veers off, and it goes totally to the right and, you know, upends itself, and it’s just fascinating.

And that’s also what this podcast is about, so that’s a perfect segue into your particular way of writing. And as you said when we were talking about this before we did the interview, you actually have different ways of working on different books. So instead of focusing on a single book, which I often do in the podcast, we’ll just talk about your process in general in the ways that it varies for different kinds of books. And the first one is a question that everybody asks, and it’s a cliché, I know, but it’s still a legitimate question: “Where do you get the ideas?”

Where do you get your ideas . . .

Or, I often like to say, rather, “What are the seeds from which your stories grow?” because that’s not quite the same.

That’s a little better question. But the thing is that ideas are the easy part. Ideas are all over the place. It’s like, how do you stop having ideas? A question I usually ask people is, “How do you not have ideas?” You know, for me, getting the ideas, like I said, it’s the easy part. They are all over the place. Emma Bull and I a couple of years ago were at an art gallery when they were living out in Los Angeles. I was out there for a convention, and the two of us went to, a lot of us, actually, went to an art gallery, and we were in a whole room, one of the rooms of portraits of people from the seventeen and eighteen hundreds, and we said, “Well, look at that? Doesn’t she look like a ghost?” And for the next half-hour, we were going down the portraits, assigning them roles, you know, “Yes, she’s obviously the ghost. And this is obviously her husband. He must have killed her. He doesn’t look very nice. But, you know . . .”, and we had this whole thing just from looking at the portraits and looking at their faces and saying, “This is what he looks like, and this is what she looks like. And, you know, that’s the scullery maid who, you know, poisoned the soup.” I mean, it was just . . . neither one of us went there expecting that, but, you know, we came out with, I’d say, things that could have been ideas for probably two or three books or maybe a series, I don’t know. Neither one of us ever did anything with them as we were just, you know, sitting there having fun. It’s just, you know, ideas are all over the place. You look at pictures, you look at things out your window, you know, whatever.

So how do you decide which ideas are worth the time and effort to turn into a finished story?

The ones that won’t let me alone. There are always ideas that keep coming back. It’s you know, you think, “Well, that’s a good idea, but it’s not ready yet, it’s not finished.” And you put it away in . . . some of those sort of go to the great idea graveyard in the sky and nothing ever happens, and nothing ever comes of them, but other ones, you know, I finish a book, and I’m casting around for the next one, “Oh, hey, here’s that thing. Here’s that story, that idea about . . . that I was going to do . . . I’ve had that idea for ten years . . .” And some ideas, there’s one of them that I think I’ve started, I thought I was going to write that book three times. And the characters that I put into the idea didn’t go the way I thought that book would go. And so, I’ve got three books out of the same idea and never actually gotten that particular idea down on paper yet. My usual process in terms of writing is to start with all the prewriting and the outlining and the, you know, coming up with a plot, the plot outline, you know, somewhere usually between five pages and twenty-five pages of details about what’s going to happen and where. It’s usually about five to ten pages, I think it is . . . five single-spaced pages, which would be ten manuscript pages, and so I do this plot outline and then when I think I’m finally ready, I sit down, and I do the first chapter, and I look at the plot outline, and I look at the chapter. And the chapter has nothing to do with the plot outline except some of the names are the same. And so, I throw away the plot outline, and I write a new one based on the chapter that I actually wrote. And I write the second chapter, and I look at the plot outline, and the first paragraph’s fine because that describes the first chapter, which I had already written when I did this version of the plot outline. But the rest of it really is not right; it has nothing to do . . I mean, more of the names are the same. And so, I ditch that, and I write another plot, and I can continue doing this for about ten chapters, until I’m solidly in the middle of the book, at which point it takes so much psychic energy to plow through the middle of the book that I stop doing outlines and, you know, by then I usually know where I’m going. That’s kind of my standard . . . as I say, the one that works for about 50 percent of the books that I do.

It’s kind of an externalized thought process, where the thinking that would otherwise just stay in your head, you’re putting it down on paper as you go along. That’s what it sounds like to me.

Kind of. It’s . . . well, not really, because that, I mean, the plot outline, sometimes I use some of the incidents that I put in there. But more often it’s, I need the plot outline because it gives me a false sense of security. I have the plot outline, so it’s like I know where I’m going. This is going to be a book for sure. I’ve got a plot outline. I know where it’s going. I don’t know where it’s going, and it doesn’t go where I thought it was going, but I have a plot outline. And the other reason I need a plot outline is because it gives my back brain something to rebel against, which is very important for me. You know, the minute somebody tells you, you know, “Well, this is what happens,” the back brain goes, “No, it isn’t. No, it isn’t. I have this much cooler idea.” So, that’s kind of my normal process.

You said that’s for about 50 percent of your books. What would be some of the books that were written using that process?

The first three or four for sure. Shadow Magic, Daughter of Witches, Seven Towers, the first of the Frontier Magic Books, which didn’t end at all the way I thought it was going to be, it developed into a series. Mairelon the Magician. The ones that don’t work like that have other things going on. Snow White and Rose Red, it was a . . . that’s the fairy tale of “Snow White and Rose Red,” and basically, I was asked for Terri Windling’s fairy tale line to do a novel version, to do a novel adaptation of some kind, of my favorite fairy tale. A bunch of us were doing it because it was a series. And so, I started that one with the fairy tale, and it had to follow the fairy tale. So, I couldn’t let my back brain go too wild in terms of the plot. But it turns out that when you do that, fairy tales are so stripped down in terms of plot and everything else that your back brain has plenty of room to go in all kinds of interesting directions. And that was the first time I tried doing alternate history, or in that case, it wasn’t very alternate, it was more history with magic in the cracks. You know, I was setting it in Elizabethan England, and, you know, John Dee was a real character, he was the queen’s magician. So was Ned Kelly. And so, I had a lot of fun doing real history along with the Queen of Faerie and various other plot elements in there. Talking to Dragons was the first time I ever did an entire book totally pantsing. I had no plot outline, I had no plot, I had no idea who the characters were. I had, I started that book with a title and the first line. Actually, I started with the title. I got the first line on the way home, driving home from the party where I got the, was talking about the title. And I just started writing the first line when I got home. And by the time I finished writing the first line, I’d actually written a paragraph, and it’s like, “OK, fine, I’ll save that for when I figure out what this book is about.” And the next morning, I woke up. “I know what the second paragraph is!” And so I sat down to write it, and I wrote the second paragraph, and I ended up with a page and a half, and it’s like, “I don’t know what’s going on, but I really want to find out, and the only way I’m going to find out is to write the rest of this book.” So, I wrote Talking to Dragons that way. Totally, totally pantsing, I had no idea what was going on until almost the end of the book. And then, of course, the prequels to that were, to some extent, I had an outline that I was stuck with because Talking to Dragons is the fourth book in the series. So, you know, when I was asked to go back and do the first books, I kind of had to . . .I got to make a few changes, but I couldn’t change anything major. The Star Wars novelizations, of course, I had the script, and they were very strict about not making changes of any sort. About the best I could do was . . . I mean, there were things I certainly made up. I made . . . the script in that scene in The Phantom Menace, the scene at the end where the, uh, Obi-Wan and the Liam Neeson character, I can’t remember his name at the moment, anyway, they’re fighting Darth Maul, and they’re leaping over things and, you know, going around this whole space and everything is this big dramatic set-piece. All the script says is Scene 20, whatever it was, “The Jedi fight.” That was it. That was it. No description of the background, no description . . . I mean, I knew where they were because it said, you know, setting, the factory, whatever, but that was it. I had known . . .you knew that was going to be, like, a five-minute set piece. So I had to pick up a lot of that in ways that hopefully would not conflict with what they did in the final version of the film. So, that was a fun and interesting experience and very different from my usual way of working. So, yeah, different things work differently.

Clearly, with these books, I mean, you’ve had books set in the Regency, you’ve had, you mentioned, the Elizabethan era, you’ve got Ice Age, all these things, and Star Wars . . .clearly, you often end up doing quite a bit of research. What’s your research process?

I did . . . the research actually, frequently, again, it’s being life, the . . . back in the day, one of the things that I started doing on about my second or third book was I started keeping a list of questions because I kept running . . . in The Raven Ring I got to, like, the seventh chapter and the cops showed up, and I hadn’t made up the cops in that world. And so, I had to stop for, like, four weeks while I made up the cops. And it totally stalled my forward progress. And I found that very frustrating. So, I started keeping a list of questions to at least ask myself when I was getting, booting up, the story, like, you know, “OK, what are the police like here?” And since I mostly do fantasy, I had a lot of questions about how magic works and, you know, things like, “Does it need a license? Do you need a license to be a magician, or is it an inborn talent? Is it something you learn in schools, or is it more like driving a car, or is it more like getting a Ph.D.? You know, what’s the education?” You know, things like that. And at the request of some people on a newsgroup that I was on way, way, way back, they wanted to know what this was like. So, I put them up, and they got consolidated into the fantasy-worldbuilding questions, which I still have on my blog, on my website. But those were kind of, the genesis is, sort of looking through them. I don’t go through and answer all the questions, every book. But I look at them and I sort of go, you know, “Am I going to need to know this? Is this something that oh, hey, that gives me an interesting idea?” You know, “I hadn’t thought about what they do for art, but if I make that one character, they’re a painter, that would be really cool and interesting. Nobody’s done that kind of thing before. I’m going to do that.” So, it just . . . and that was really where I got interested in a lot of the aspects of worldbuilding that led me eventually to do this class for Odyssey that I’m going to be teaching in January.

Well, that seems like as good a point as any to talk about that class. What will that look like, and what’s the process if someone wants to be part of it?

Well, they would go to the Odyssey website and register, they’ve got, you know, all the details there. I don’t have . . . I should have copied that website. I think it’s Odyssey.com or Odyssey.org.

Yeah, I’ll put a link to it. I actually do have a description in front of me here somewhere . . .

Yeah. There’s . . . basically, what I want to do in the class is, there’s basically two parts to worldbuilding. There’s the part that everybody thinks of, which is the making it up part, where you’re . . . you know, the Tolkien appendices, where you’ve got massive amounts of information about, you know, what the pottery is like and what the artwork and the culture and the history and the battles and how magic works and all this other stuff. That’s the first part. And that’s important. You need to think about that. But the second part is really the key, and that’s getting it across to the reader in the text, because Tolkien is really the only one who can get away with putting a million appendices at the end of their book and having everybody actually read them. So, you know, all of the important things, getting across . . .and that worldbuilding is something that everybody has to do in every book, because whatever your characters are, wherever they are, whatever culture, even if you’re in 2020, there’s going to be a sizeable number . . if I’m writing a book set in 2020 in Minneapolis, there’s going to be a sizable portion of my readers who have never been to Minneapolis, who don’t know what it’s like, who have no idea what things . . . you know, who’ve never even seen it on television.

Even if you pick someplace like London or New York where you know what all the key buildings and such look like because everybody’s seen them on TV and the movies, there’s an awful lot of London that people just don’t know what it’s like unless they’ve been there and haven’t been there. And there’s going to be people still who haven’t seen it on TV because they just don’t watch those shows. You know, so, even when you’re looking at a real-life place and, of course, the further away it is from the experience of your initial set of readers, the harder or the clearer your presentation of that world has to be for it to be appealing. The Harry Potter books are a great example. I mean, they’re quintessentially British, you know, set in the British Isles, United Kingdom, England and Scotland. So much of it is very, very, very British, and yet she can . . you don’t have to know that to love the books because she does such a good job of getting the feel of what it’s like across, both in the Dursley’s, the real world and in the wizarding world. You know, there’s translations into Japanese and Indonesian, and all these different places and languages, and they’re appreciated by millions and millions of people all over the world who don’t need to have a cheat sheet of what this means because it’s British and they don’t, you know, they’ve never been to Britain, and they don’t really get how it works. You have to get it across to people, and that’s what I’m hoping to start with, sort of some of the basic aspects of worldbuilding, of the making-it- up part, and then talk more about the getting it across part towards the end.

It is odysseyworkshop.org. I looked it up here.

Yes, that’s excellent.

Well, one of the things that’s mentioned in the description is how worldbuilding can affect the characters. And we’ve talked a bit about your plotting process. But where do you, how do you find your characters, and how much work do you do on them beforehand, and how much do they just grow during the process?

It depends on the book. It depends on the character. A lot of the times, a lot of the times, they just sort of walk into my head. If you’re starting with a character, you do the worldbuilding, and you can start anywhere. And sometimes it starts with character. You know, a character walks into your head, and you sort of look at them and go, “OK, what are they wearing? Swords and a kilt. That’s interesting. All right. We’re looking at maybe medieval Scotland or maybe some kind of roleplaying. Where is this person from? How did they get this sword? Is that a real sword, or is that just for show? Is that a kilt? You know, it’s not plaid. Why are they not wearing . . . OK, then it’s not Scotland. So, who else wears kilts? So, I’ve got a world that has . . . yeah.” And I’m just making this straight up out of, off the top of my head. This is how it works. You know, you dig into the characters, and a lot of it is digging into the character. As I write, I tend to write my way into the characters, as I usually start more with the plot, which is really kind of weird because a lot of the time, the characters are what drives the plot. But the world that you live in shapes the person in real life and in fiction, and it makes a difference. What the world is like is going to shape what the person is like. If you’re actually looking at a medieval peasantry, they’re not going to be literate, most of them. Which means they’re not going to have read books, but they will be oral storytelling, and that’s going to affect the way they see stories and process. You know, skills are going to be different. The kinds of things that they’re used to are going to be different. You take somebody from the 1100s, heck, even from the 1700s, bring them into a room and flip the light switch and they’re going to go, “Magic!”

Mm-hmm.

You know, “Lights came on! Oh, my God. Magic!” It’s all in what you’re used to. There’s a wonderful book by Sylvia Louise Engdahl called Enchantress from the Stars, in which there are three different viewpoints.

I know that one!

Yeah. Where you’ve got the fairy tale version, which is the way the peasant, the native, sees it. And you’ve got the viewpoint of the highly technological aliens who are coming in a . . . to them, it’s all about the, you know, their technology and their machines, whereas, of course, to the native guy, it’s all magic. And then you have the gal from the super-advanced society that’s trying to keep these two very different cultures from clashing, to whom they’re both kind of childish. And it’s really the different views, which are predicated on the cultures and the worlds from which each of these characters come. And so, yeah, the world shapes the characters as much who the character is; if you’ve got a clear idea of the character, then that pretty much defines what the world has to be because that character came out of the world. And you can tell a lot about the world by looking at the character and understanding where they came from and how did they get these ideas or their these viewpoints or beliefs or, you know, this drive to, you know, save the world or destroy the world or whatever they’re going to do.

Once you have a plot and character and all of that, what does your actual writing process look like as far as the actual physical act? You started in typewriter days, as I did . . .

Pardon me?

You started writing on a typewriter, I presume, as I did . . . or first, longhand, I suppose, to begin with . . .

I did. I did typing. I took typing in high school. And I’m forever grateful to my mother for making . . . it’s one of the fundamental things I think that I recommend to everybody is, if you want to be a writer, learn to type, learn to touch-type.

Touch-type.

So, I have a very good friend who blew out several disks in her neck because she’s a hunt-and-peck typist, and she looks down at the keyboard as she types, and then she looks up at the screen to see what she typed, and she looks down at the keyboard as she types, looks up at the screen and she types, and after 40 years, she’s had several disks in her neck . . . and it’s extremely painful. And touch typing, you don’t have to worry about that.

But I presume you work on a computer now.

Yes, absolutely. As soon as practically as soon as they came out, I had one of the very first Apple II Plus’s, and I thought I’d died and gone to heaven.

Yeah, a Commodore 64 was my first one.

I was doing cut and paste when cut and paste meant . . .

Cut and paste.

Scissors and . . . scissors and tape. And yeah, that was exciting. I still remember that.

Do you write a certain number of hours a day, or how does that work for you? And do you work at home or do you like . . . well, everybody works at home now, but do you like to go out to other places to write or how does that all work?

A little bit of everything. Sometimes it helps to, you know, take the laptop to a coffee shop, now that I can do that. It’s been an evolution because, of course, back in the day, you didn’t take the typewriter any place because it was too heavy. And then the computer, of course, was desktops. It wasn’t until laptops came along that it was even a possibility to take your computer out to a coffee shop casually and, you know, out any place. And so, you know, where I write has been kind of an evolution. I’ve always had a desk, at least a desk someplace, and usually had an office. You know, there’s . . . sometimes the office was the spare room, to begin with. But I had an office, and I mostly work in the office, sometimes haul it out someplace else just to get a bit of, you know, change of scenery.

Are you a fast writer or a slow writer?

I don’t know. I’m a plodder. I am not . . . most of the time, I’m a plodder. I’ve had a couple of books where I did a burst writing. But most of the time, it’s a, you know, if you write one page a day, every day without fail, at the end of the year, you’ll have three hundred pages, which is a book, and you can take Sundays and holidays off. And that’s what I do. That’s what I started doing. And that’s basically what I try and do. And it’s gotten harder over time as other life things keep interrupting and getting in the way. It’s been very difficult to concentrate in the past, oh, what is it now, eight, nine months?

Feels like forever.

But yeah, since about last February, it’s been really difficult to concentrate. That, too, depends on whether writing is more like a hobby or more like an escape or whether it is something that requires focus and mental energy, and really, for me, it’s kind of both those things. So, sometimes it works as an escape, and then it’s like, yeah, head down in the book because that lets me ignore all the horrible things. And sometimes, I’m so distracted by all these other things that are going on that I can’t get head down in the book. So, you know, it varies.

Once you have a finished draft, what does your revision process look like? Do you use beta readers, or do you just revise it yourself?

Oh, I use beta readers. I use beta readers everyplace. I am a rolling reviser. It’s one of the many things . . . I talked about this a lot on the blog. I also have a blog, at pcwrede.com, where I talk about writing and process and have been doing for . . . God, ten years now! That’s kind of scary. But I talk about the process, and I’m a rolling reviser. You know, some people have to do the whole book all the way through and then go back and write it. Some people have to have to get it right almost the first time because their stuff sets up like concrete after, you know, 24 hours, after they’ve let it alone for 24 hours, it’s practically impossible to change. I’m kind of . . . I need to have, what has been written, I really need to know somewhere in my back brain that it’s right, quote-unquote—picture me doing air quotes—in order to continue to make progress. I have learned over 40 years of doing this that I can at times put in a little note that says, “Fix this later,” and actually go back and fix much later. But most of the time, if I realize in Chapter 15 that I just had this brilliant idea, but for it to work, I need to plant something in Chapter 2 and remind people about it in Chapter 7 and 12, I have to stop and go back and plant it in Chapter 2 and do the reminding in Chapter 7 and in Chapter 12 before I can continue with Chapter 15 because when I do the plant, when I do the reminding, it changes what I’m having happened just a little, just enough that in order to get it right from here on out, I have to know what happened back in those places where I’m planting this thing. So, I tend to . . . and the other thing is that when I get really, really stuck, I’ll go back and I’ll start at the beginning, and I’ll just go through and fix things and revise things and reread things and fix them, and usually by the time I get back, I’m not stuck anymore, you know, because I’ve changed enough things or I’ve seen enough things where it’s like, I’ve got the ideas to move on with.

Who are your beta readers, and what do they do for you?

It’s varied a lot over the years. Lois McMaster Bujold and I trade manuscripts all the time.

Pretty good beta reader.

She was . . . I was one of her first, actually. I had . . . back when I sold Shadow Magic, I went to the Chicago WorldCon and met Lillian Stewart Carl, and we, I offered to trade manuscripts with her by mail, and she said, “Well, you know, I don’t I don’t really need that, I have a writers’ group.” This was before that, you know, when I was still hunting for more input. I was in the Scribblies, but I was still hunting for other input, outside input. And she said, “I don’t need that. I have a good writers’ group, but I have this friend in Ohio who doesn’t have anybody. She’s out in the wilds of Ohio. She doesn’t have anybody around who reads or writes science fiction fantasy. Can I give you her your contact?” And that was Lois. And so, you know, she and I started trading critique by mail. I ended up with, like, a four-inch stack of . . . this was before email. So, physical letters until we went, until we did go to email. Then eventually, she moved to town, which made it much easier. But anyway, she’s one of my beta readers. Pamela Dean still is. Caroline Stevermer frequently. Several non-writer friends . . . you know, Beth Friedman. God, I’m missing somebody . . .

That’s the trouble with starting to name names.

Yeah, yeah, it is. It’s well, especially, there’s a bunch of people that nobody would recognize that, you know, I could name the names, but, you know, it’s not going to mean anything to anybody. But, you know, sometimes the best beta readers are people who are not writers; they’re just readers who are really good at articulating what’s going, what is a problem here, or what they like about this or don’t like about this.

And what kind of feedback do you typically get from your readers that . . . what sorts of things do you find you need to work on?

It varies. Everyone . . . and sometimes it’s the same old things that you thought you had gotten rid of years ago. Sometimes it’s, you know, there’s character stuff, there’s stupid, stupid things like dialogue tags and repeated words, you know. One I remember specifically because it was so annoying was somebody who pointed out that I had used a very unusual phrasing like three times in the same chapter. And it’s like, “How did I not notice that?” You know, but I mean, it’s everything from really picky little details to questions about characters that are very enlightening, like, you know, things like, one asked, you know, “Are these two characters gay?” And I went, “Son of a gun. They are. I didn’t know that. OK.” You know, so it’s there for people who want to see it, but it’s not a big point. Mean, I didn’t know they were until somebody pointed it out. You know, it’s like, “Oh, yeah.” And so there’s things that are . . . things about the characters that I hadn’t even realized, things about the world, things about the plot. Just, you know, major things, and then, of course, the minor word dinks and nitpicks.

And then the manuscript will go to an editor. What kind of editorial feedback is typical for you? Do you find it’s pretty clean, you don’t have to do a lot, or there are occasionally some . . .

It depends on the book.

And the editor, I would presume.

And the editor. They’re very different. There is one editor that, it was always questions. She never made any recommendations; it was always questions about what was happening. I had another editor . . . Jane Yolen was lovely. I mean, she was fun. We were friends. She edited the Enchanted Forest books when she was at Harcourt. And she was . . . we were good friends. In fact, she kind of was the one who browbeat me into writing the prequels. And so, it’s all her fault. But I turned in the first one, and I got back two pages of editorial comments that started with, “Does your husband know about your love affair with a semicolon? Seventeen on one page is too many.” You know, and she was absolutely right.

I like a good semicolon, but that does seem excessive.

It was excessive. It was, like, a manuscript page was about, I think I had my printer set to do 25 lines, and 17 of them had semicolons. It was just way too much. So, yeah, it varies. And then I had one editor who basically . . . had two different editors, in two different places, I had ask for scenes, where I had not put in a particular scene the character . . . in one instance, the character wasn’t there, and in another instance, I was skating very quickly over that part, and it just didn’t seem . . . and the one where I was skating over it wanted the set-piece with that particular scene and the other one, the character wasn’t there, and the editor said, “This seems like a really important scene, and I think you should write it.” So, I had to write ten thousand words to, you know, instead of having the character told about it in a three-paragraph summary, I had to figure out how to get her to go along so she could watch it. And it took about ten thousand words to interpolate that into the book.

But it made the book better.

Oh, yeah. Oh yeah. I’m very pleased with how it came out, but it was a lot of work. So, it really depends. A lot of the time it is pretty clean, I think, but I don’t have anything to judge by except my own stuff, really. So how would I know? I don’t know what the editor sees all the time.

Yeah. They see a lot more stuff than the authors do. My editor is Sheila Gilbert at DAW. And, of course, she’s been doing this for a very long time.

Yes

She’s seen a lot of manuscripts. And she notes . . . she just sees things that I don’t see..

Yes. Yeah, yeah. They see things you don’t see.

And now we’ve actually gone past the hour, but nobody’s counting, so . . but I should wrap it up here.

Well, I should have warned you upfront, I can talk about writing for hours, literally. I thought . . . I was supposed to have a one-hour interview with somebody at my alma mater, and we ended up talking for five hours, until I got hoarse. So, yeah, I can talk for a long time about writing.

My record is still Orson Scott Card, who went for two hours by the time we were done. So, you know . . .

Ah, yeah.

We’re not there yet. But just to wrap it up with the big philosophical question, really, three: Why do you write? Why do you think any of us write? Why do we tell stories? And why stories of the fantastic, specifically?

Let’s start backwards. Stories of the fantastic is because I can’t seem to write anything else. I tried to write a mystery once, and it had wizards in it by the second chapter, so I gave up. I was like, that’s what I write. That’s what my back brain hands me, so that’s what I write. Why I write is, again, I just, I mean, I love reading, I love writing, I love telling stories, I’ve always loved telling stories, and writing is a way of doing that. I mean, I think I would write stuff even if I wasn’t selling it and nobody was reading it. It would not be as easy, and it would be very disappointing. Certainly, at this point, it would be very difficult since this is how I make my living. But really, I like the process. I like it even though it’s frustrating and annoying as all get out and, you know, can drive you just absolutely mad at times. It’s still . . . I love the feeling that I get when I know I nailed it, when it’s like, “Yes, there’s that scene, and this is that thing.” And I have this cool thing going, and I got it. And there it is. “Yes, that’s what I wanted.” I don’t know if anybody else is seeing it, what I saw, and sometimes they don’t, and sometimes I end up having to fiddle with it. But there’s still that moment when there it is down on paper, that scene I’ve been waiting to write for so long.

And I also love the analytical side of it, you know, figuring out why things work, why using this viewpoint is more effective than using that viewpoint, you know, what’s going to work best for this story, how . . . I love doing that. I love it. I mean, that’s mostly what the blog is, is different angles of a view on everything from . . . well, just pretty much every aspect of writing, I mean, I’ve been doing it for ten years, I think I’ve covered pretty much everything, and I’m still talking about it, which tells you how long I could go on about writing. That’s me, you know, I just . . . the other thing is I do it so that the voices in my head will shut up.

I’ve heard that from a lot of authors. A lot of authors put it that way.

And it’s not necessarily the characters’ voices, it’s the stories themselves. You know, it’s . . . I’ve shot past my exit numerous times on the freeway because I’m sitting there going, “And then they go, right? No, no, no, no, they’ll go left, left. And there there’s . . . yes. And the bridge is out. And the . . .” You know, if I don’t put it down on paper, it keeps changing in my head, and it won’t leave me alone. And so, I have to go home, and I have to write the scene where the bridge is out. And then I’m done with the damn bridge. It’ll leave me alone. But I have shot past the exit multiple times doing, you know, telling myself stories in my head.

Why do you think on the bigger scale, why do any of us write? Why do you think we do this? As a species, I guess.

As a species? I think it’s to explain ourselves to ourselves. You know, it’s . . . stories are a way of transmitting life lessons and teaching people about things that are going on in a wider world. One of . . . I think I heard this bit from Jane Yolen. She had been reading about an anthropologist. She’s very big in fairy tales. And the anthropologist had been collecting fairy tales from native cultures in the north. I think the Inuit was one, but there are several others, and one of . . . and their fairy tales, their stories, are really grim, and they have this custom of, in the wintertime, when it’s dark for 24 hours or very nearly a day, everybody gathers in a hut. And, you know, the children are all there, and they tell these horrible, horrible ghost stories, creepy, scary, nightmare-inducing stories. And at the worst part of it, somebody, one of the adults, sneaks out and they beat on the outside of the tent, you know, to make the scary parts even scarier. And the woman said, “Why do you do this? Why do you do this to your children?” And the person she was interviewing said, “Because they need to be scared. They need to learn how to be scared in a safe place so that they won’t freeze up when it’s a real emergency.” Because if you freeze up when it’s 50 below zero, and you’ve just gone through the ice, you are a dead person. You have to be able to continue to function, and that’s the kind of things that stories do. Most of us are not in that dire of an environment, that we’re under those kinds of threats, but there’s still. . . they are ways of conveying lessons about people, about what is right and what is wrong about dealing with other people, about living in the world, you know, about what kinds of things are mistakes and what kinds of things, you know, you might not recognize as a mistake right now. But in 20 years or 40 years, you will. And sometimes those things are buried really, really deeply entrenched, and they are ways of explaining to ourselves what we’ve learned about ourselves and about other people and about the world. I think that’s kind of as deeply philosophical as I can possibly get on this.

Well, it certainly seems like a good answer to me. OK, let’s wrap it up by finding out what are you working on now? What’s coming up next from you?

OK, I am in the process of doing what I hope will be final revisions to another children’s book called The Dark Lord’s Daughter. It’s about a 14-year-old girl who is, uh, you know, she knows she’s been adopted, and her family has, her adopted family, has kind of fallen on . . . they’ve been having some difficulties, and she and her adopted mother and her little brother are off at the state fair, and they are approached by a gentleman in what looks sort of like a Darth Vader outfit who says, you know, “My lady, I have found you!”, and the next thing they know, the three of them have been transported to an alternate universe. And she finds out that she is the daughter of the former dark lord and is expected to come and take over his kingdom.

That’s a great setup.

And it is nothing like what either side is expecting. She is not what they were expecting to get, and they are, you know, the dark lord’s kingdom is not at all . . . well, let’s put it this way, they had ten years to deteriorate, and it’s deteriorated pretty darn bad. So, she’s got a lot of work to do. And, of course, she’s got her mother and her little brother along to make life interesting.

That sounds fun.

So I’m working on that. And, I don’t have a pub date yet because I’m way behind, and I don’t get to know when it’ll come out until I actually turn it in.

Publishers are annoying like that.

Sometimes. Sometimes.

And where can people find you online?

PCWrede.com. And that’s my Web site and the blog and a lot of other useful information if you poke around on it a bit.

Any social media accounts to mention?

The blog is really the only place where I spend a lot of time. I do have a Twitter account where I mostly make announcements, and there is a Facebook business page, which again is . . . that’s not really run by me, but it also has a lot of announcements about, you know, what’s coming up with my books. Every once in a while, I post something to Twitter, but I’m not really super active there. I have too much else going on.

And once again, of course, you’re teaching the World Building in Fantasy and Science Fiction workshop for Odyssey Workshop.

Yes, I think that’ll be fun.

And that runs January 7 to February 4. And the deadline, I believe, is December 9, if anybody’s listening and wants to register.

Yeah. And it’ll be, it’s three classes with about two weeks between. So, you’ve got time to actually apply some of this stuff in between and hopefully come up with new and interesting questions to ask.

OK, well, I guess that wraps it up, then. So, thanks so much for being on The Worldshapers.

Ed, thanks for being here.

I enjoyed it. I hope you did, too.

Thank you for inviting me!

Bye for now!