Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

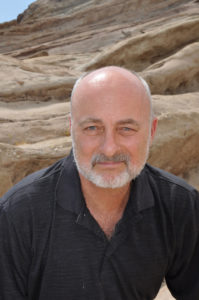

An hour-long conversation with world-renowned, bestselling author (and scientist, speaker, and technical consultant) David Brin, winner of multiple Hugos, Nebulas, and other awards, with a focus on his books The Postman, Kiln People, and Foundation’s Triumph, as well as his thoughts and advice on writing…and many other topics.

Other links David provided or mentioned:

TASAT (There’s a Story About That)

David has been speaking and writing about Artificial Intelligence a lot. Here’s video of his talk on the future of AI to a packed house at IBM’s World of Watson Congress, offering big perspectives on both artificial and human augmentation.

David on using science fiction to teach science

David on teaching science fiction

Pop Culture: Star Wars to Tolkien to…

Articles and speculations about Existence

The Introduction

David Brin is a scientist, speaker, technical consultant, and world-renowned author. His novels have been New York Times bestsellers. He’s won multiple Hugos, Nebulas, and other awards, and his books have been translated into more than 20 languages.

David serves on advisory committees dealing with subjects as diverse as national defense and homeland security, astronomy and space exploration, SETI (the search for extraterrestrial intelligence), nanotechnology, and philanthropy. He’s served since 2010 on the council of external advisors for NASA’s Innovative and Advanced Concepts Group, which supports the most inventive and potentially ground-breaking new endeavors.

In 2013 David helped establish the Arthur C. Clarke Center for Human Imagination at the University of California San Diego. He’s been awarded numerous honors, including the American Library Association’s Freedom of Speech Award for his nonfiction book The Transparent Society: Will technology forces to choose between freedom and privacy?, which deals with secrecy in the modern world. David appears frequently on television, including most recently on many episodes of The Universe and on the History Channel’s most-watched show ever, Life After People. His scientific work covers an eclectic range of topics from astronautics, astronomy, and optics to alternative dispute resolution and the role of neoteny in human evolution. He holds a Ph.D. in physics from the University of California at San Diego, which followed a Master’s in optics and an undergraduate degree in astrophysics from Caltech. He was a postdoctoral fellow at the California Space Institute and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. He has a number of patents that directly confront some of the faults of old=fashioned screen=based interaction, aiming to improve the way human beings converse online. He lives in San Diego County with his wife, three children, and one hundred very demanding trees.

The Lightly Edited Transcript

Now, the first thing I have to ask you is, what makes trees demanding?

Oh, well, it’s Southern California, you know. It’s not an area where trees of substance would normally grow. As you drive north from San Diego to L.A. you pass through Camp Pendleton, the great big Marine base, and you see what Southern California was like back for the Native Americans and the early Spanish, and it’s not a lot of oak trees and not a lot of anything else but it had its own ecosystem, and we have to try to respect nature.

Well, one reason I asked, I live on the Great Plains, in Saskatchewan, northern plains, very northern plains, and there’s a famous writer from Saskatchewan, his name is W.O. Mitchell, and one of his books was called Roses Are Difficult Here, and that’s what that reminded me of.

Now, we met, I think for the first time we’d actually spoken to each other, at the World Science Fiction Convention in San Jose this year when you just happened to stop by the SFWA, Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America table where I was volunteering, and that’s when I took the chance to invite you to be a guest. So, thank you for saying yes.

It’s terrific. We’re colleagues in a very, very strange cult. There are some religion and cult-like aspects to science fiction, but it’s a cult that believes in raising its children to out to have doubt and ask questions. It’s a sort of a fundamental ethos. If your children come up to you, having been raised in this culture, and they say, “I have different ideas than you, Mom and Dad,” our reflexive response is, “Ooh, tell us about it.”

In most of these episodes I’ve focused on a single book that the author wants to talk about. But you suggested three you wanted to talk about, The Postman, Kiln People, and Foundation’s Triumph, which are all quite different.

We’ll get to those in a bit, but first, I want to take you back into the mists of time. When did you first develop your interest in this strange cult of science fiction and when did you start writing it—and which came first?

Well, I began writing in the fifth grade. I had a teacher who encouraged her students, and I enjoyed it. Of course, I came from a family of writers, going back generations.

But what’s interesting is that I knew from the start that history shows that every human civilization had artists. Now, in our civilization the artists and the entertainers are in charge of the mythic system, and so they extol how important art and entertainment and storytelling are and they are. They’re wonderfully human and important but they’re not rare. If you look across human history there’s never been a human civilization that didn’t have art, it fizzes from our pores, it bubbles, it pours out of us. Our greatest human talent is delusion and artists cater to it honestly by saying, “Hey, here’s another cool delusion,” whereas often politicians and priests and some other professions are shysters. They say, “this untrue thing is true.” But I looked around and I saw that only a couple of human civilizations ever devoted anywhere near as much in resources and attention to actually finding out what’s actually true.

I’m a child of Sputnik and I saw that we were developing hundreds of thousands of skilled people to try to find out what’s actually, objectively true, instead of artistic “Truth.” And I wanted to be part of that. I wanted to be part of something that was profoundly honest, a team effort that was going to transform human civilization. So, I made my writing a hobby rather than my central focus. I went to Caltech and then I went on to UCSD, got my doctorate in astrophysics, but all along the way I had this hobby and I developed it calmly and gradually. That’s the way I recommend to bright young writers: find something that you love that you will be paid for and make that your day job because usually you have to, you know, you can’t ignore the alarm clock if you have a job. But passionately have an avid artistic avocation and grow into it.

You know, parents all through time have said the right message in the wrong way to kids, and that is, “Well, it’s nice you want to go into this art, but have a backup plan.” But if it’s a backup plan and you wind up doing that thing for the rest of your life, then it’s always something that failed. The exact same message could be, “You are large. You can do several things. You’re a positive sum, you know, you’re more than one thing. So be good at something that people will pay you for and be good at something that you don’t give a flying patoot if anybody pays you for it. That’s means you’re an actual artist. If you have to write just for yourself, then you’re writing just for yourself because you must. As it happened, I did good work in science, but civilization very rapidly decided that it valued my delusions, my industrial-grade fabricated artistic delusions, much more, was willing to pay me more, willing to flatter me more, and so I was dragged kicking and screaming mostly out of science. May that happen to you. But if it hadn’t happened, I would still be coming out with books more seldom while I did something solid as my day job.

You said you started writing about the fifth grade. Did you share that writing while you were still a young a young writer? This is something I often ask young writers when I’m teaching writing: it’s important to find out if you’re telling stories that people want to read. Did you take that approach or were you keeping it all to yourself there for a while?

Well, I find that writers are just about the most varied type of profession. Some people, they’re a shy, they don’t want to share what they’re doing or if they tell the story even verbally, describing it to somebody, it takes away from the need to tell it. I’ve never understood that way of looking at things. The more often I describe a story or talk about it or poke at it the more I know about it and the more I the more I want to tell it well. So, you know, we’re varied, we’re very different.

Same thing with attitude toward criticism. If you want to be good at something, you have to get past your delusions of how to do it because, you know, you’re just not going to do it right at the beginning. You’re going to make a lot of mistakes, and there are a lot of skills, especially in writing, especially in fiction, that are almost invisible. The only way you’re going to get better in most arts is through apprenticeship or through taking criticism.

But the problem is that although criticism is the only known antidote to delusion, we hate it. We inherently hate criticism and so we make sure that others can’t criticize us. This is the root of the horrible thing that’s called human history. The horrible story of terrible events called history is rooted in the fact that leaders are human, and they therefore suppress criticism. They don’t want to have criticism. It’s anathema to them. The more mature they are the more they try to overcome this. And if they’re immature they try to repress criticism.

The most mature profession is science because in science, all of the apprentices in science at university are taught to recite or to know the great mantra of science, which is, “I might be wrong. Let’s find out.” And so, after 6,000 years of civilization, science has led the way, journalism also and some others, to enshrining criticism as the central antidote to error. But we’re still human and we try to avoid it almost reflexively. Even if you’re a leader and you say, “Give me the bad news.” your body language warns your subordinates that they’d better be careful. But the great breakthrough of our enlightenment was not freedom per se, not justice or equality per se, but the things that freedom and justice and equality and enable. And that is a confident civilization filled with a maximum number of people who can criticize each other because reciprocal criticism is how we find mistakes as we charge into the future.

Well, all right, so I got a little carried away there. The point is that the one thing that you can do as a writer that will make the biggest difference is to enter into situations where you cannot avoid your work being criticized and getting feedback. And that means workshops. One of the things I did was I took creative writing classes at local community colleges. Don’t be a creative writing major, for heaven’s sake. I mean, that’s the silliest thing you could possibly do. As I said, study something that would be useful for honorable and fun day job, because you need to have that alarm clock, but take, you know, creative writing classes because they give you a deadline: I have to hand in ten pages of a chapter I’m working on or a short story next week. It’s a deadline. I have to fulfill it. So, you write 10 pages. Well, at the end of a ten-week class you’ve got 100 pages. And if it’s discussed in class you can find out where you failed to get the point across, where you failed to communicate. I mean if the other people in the class said, “I was confused here, I didn’t get it,” you know, you don’t respond by saying, “Oh, but didn’t you understand on page two where I said…” No! What you did on page two failed and it’s up to you to find a way to do it better.

When you get a little more advanced you can collect names and create a workshop that’s a little more a little more ahead, a little more professional. We had one in San Diego when I was getting started that had Peyton Murphy, Richard Kearns, Michael Reeves, Greg Bear, occasionally Kim Stanley Robinson.

That’s not bad.

It was an amazing workshop, and boy were we brutal with each other. And there are writers out there who do not want to be brutalized with criticism. It’s not their fault that they’re a little more shaky and fearful. So, you find another way to do what I’m talking about and you can do it online. There’s a website called Critters, which is a site where, if you’ve participated in the criticizing of, say, 10 other people’s manuscripts, then it’s your turn to have yours critiqued. And, of course, that leads into the fact that the Web has offered people a way to get published that was never available before. Because there are basically two ways to get to get your art noticed. One is to be plucked up by the publishers, to be noticed by the great agents or publishers out there. And that used to be the only way to get a book published. But there was a second method for music. You might get suddenly noticed, your demo tape, by a music company, or you could climb the ramp—because the arts are all pyramidal. There’s 10 people who dream of writing for everyone who writes or even tries. There are 10 who try for every one that ever finishes anything. There’s 10 who finish something for every one that ever tries to submit something for publication. There are 10 of those for every one who gets anything published, and so on up the up the line.

My daughter’s a dancer, and we always say that at the peak there’s a couple of dancers who’ve come out of the studio who have gone into professional careers, but you start with 300 little girls in pink body suits down at the bottom. And then over time it gets winnowed down and down and down until eventually somebody emerges at the top. So that’s quite true, all forms of art I think are like that.

Yeah, well, for every 10 writers who can, you know, sort of make a basic living at writing, you know, there’s one of me, but for every ten of me who are comfortable from writing there’s a Stephen King out there and we’re shaking our fists up at him. “Curse you!” But actually, he’s a sweet guy.

J.K. Rowling and her castle.

Right. Absolutely. And fortunately, she’s very sweet, too. So, you can’t really hate her. The point is that climbing that pyramid used to take being plucked by a publisher or an agent who notices you out of the slush pile and that slush pile process still exists and it existed for music, but for music there was a ramp of the pyramid, and that was the ramp of merit, local merit. You would give a local concert, you’d be the opening act for a local concert, you’d do well on amateur night, you’d become the relief band on weeknights. You cut a local album, get a little scene going, and work your way up. Well, now that ramp exists for writing. That’s a long-winded story to basically get to the same point. Now you can have that ramp by publishing your works online. And the good news is, nothing’s going to stop you from having a book. What used to be called vanity press, well, now it’s hard to tell the difference. And you’re going to have a book. The bad news is that a million bazillion bazillion bajillion other people have their self-published books. So, getting it to stand out is going to take entering some kind of a rumor mill or self-publicization things, like that. And, you know, we all know the examples of people who really made it that way—Fifty Shades of Color Purpleor whatever. But the bad news is it’s hard to stand out in that world. But I suppose we should move on and talk about books.

So, when you started writing, when was your first sale? What was your first professional success as a writer?

Well, I spent three years writing my first novel, Sundiver. I wrote a couple of short stories, and usually people do their apprenticeship with short stories, and workshopped a few, but I didn’t really do much of anything with them. My story’s very atypical. The very first publisher to which I ever submitted anything was Bantam Books, for my novel Sundiver, when I felt it was ready. And it took them a little while to get around to reading it through the slush pile, but they made me an offer three times the usual starting rate for the first thing I ever submitted. So, I only started getting rejection slips after my first novel was in the works for publication. And when people shake their fists at me for that I can just sing, “Fairy tales can come true, it can happen to you, if you’re young at heart,” and there, now I just sang on radio.

Well, on the Internet anyway. I would say I think you would say too that most of your science fiction falls into what’s called “hard” science fiction with a lot of technological speculation. What do you make of that distinction between hard and soft science fiction? Sometimes I think they’re not really even in the same genre. In some ways, soft science fiction, some of it is so soft that it’s indistinguishable from fantasy. I’m thinking things like Star Wars. What do you make of that?

I think it’s multispectral. I think it goes in many directions. For example, I think the biggest difference between fantasy and science fiction is not the furniture. Star Wars, for example, has spaceships and lasers, but it is fundamentally fantasy because of the power arrangements, because it’s a feudal mythological society in which these superior beings, those with Force, are all important and average people are not. Well, this goes back to the myths of the Iliadand The Odysseyand most of mythology in most of human history. So, this is the old mother art form, and, you know, one could call it fantasy today, but science fiction is impudent. And so, I call a science fiction story one in which change is the topic: not so much science, not so much technology, but the notion that, sociologically, our society might shift under our feet and that the old ways may come apart. That could lead to dystopias where the old ways are our ways and they come apart, like the greatest self-preventing prophecy called 1984, which helped to prevent itself from happening (God, I hope so) by, you know, delivering dire warnings. Soylent Greenwarned us about climate change and ecological destruction and recruited millions of people to be environmentalists. Dr. Strangelove. On the Beach. Fail Safe. These all helped to prevent nuclear war by pointing out ways that it might accidentally happen.

So, this is what science fiction is to me. And so, you know, the hard-scientific aspects of the furniture, of the situation, aren’t central to me. Now it’s true I always just pile in stuff that I’ve learned and I’m a packrat. There’s more biology in my books than astrophysics because that’s where a lot of exciting stuff is happening these days. But The Postmanhas very little in the way of science and technology because it’s about the fears that I grew up with as a Baby Boomer, diving under my desk when I was a child in elementary school because the teacher did a nuclear war drill. And a lot of people are writing to me about The Postmanbecause, you know, not just because of the movie but because nowadays it’s looking frighteningly as if there’s some relevance to the story.

Since we’re going into that and that’s one of the ones we want to talk about, maybe you can give a very brief synopsis or description of it for those who for some unfathomable reason have neither read it nor seen the movie.

This is my most famous book because of the Kevin Costner movie. He made a movie in 1998 and in probably one of the greatest fails of movie-release timing in the history of the world, released it…he sent out an email saying we’ve got it made this Christmas holiday release, our only competition is James Cameron’s silly remake about a sinking boat. So, he released this movie opposite Titanic,and I don’t know why that’s not the most famous aspect of this whole thing. Anyway, so people ask me what I think of the movie and sometimes they’re surprised to hear that I’m even-tempered. It’s certainly not something that I’m ecstatic over the way Andy Weir is so happy over The Martianor Ted Chiang is so happy over the movie The Arrival. They had reason to be delighted there, and they were treated very well, by the way, by the directors and producers of those flicks, asking them advice and all that sort of thing. Kevin Costner didn’t treat me well. We exchanged maybe 12 words. You’d think that if you were going to make a movie of somebody’s book that you’d take them out to dinner. I never had a beer. But Hollywood is kind of like that. It’s, you know, what ego does to people. You have to take it with a grain of salt. It makes for very frail, very large egos. What mattered more to me was that the script by Brian Helgeland, with a lot of input by Costner, was sweet. It was bighearted. It conveyed a lot of the heart message of my book and that was the most important thing. If they had betrayed the soul…

The book is a post-apocalyptic story. It’s about the fall of human civilization, the thing we fear most, but it’s sort of an answer to the whole Mad Maxgenre in that the saving of whatever there is to be saved is not done by the lone hero and a sidekick. The hero does not defeat the bad guy by punching him in the face. To whatever extent good things happen, the good news is brought by the real heroes of our civilization, and that is citizens: people who remember that they were once mighty beings called citizens with great power, magnificent power, of cooperation and to get things done, and the hero’s principal job in this story is that he tells a lie. He tells people in isolated villages that the United States still exists and that it’s coming and he’s a postman and he’s delivering mail and people are so ashamed of how far they’ve fallen, they’ve let themselves fall, that they reopen schools, they reopen the post office, and everywhere he goes, like Johnny Appleseed, America is reborn, just because people believe that America has been reborn. They’re the ones whose start the rebirth.

And this is something that Costner captured. He captured this basic heart essence beautifully, and for that I forgive the fact that he scooped out and threw away almost all the brains. One thing about Kevin Costner is that I think he’s a cinematographer genius. I think this movie is musically and visually one of the dozen or so most gorgeous ever shot. So, what are you left with? You’re left with gorgeous, bighearted and dumb. Well, you know, there are worse things in the world than gorgeous, bighearted, and dumb. That’s what my wife married!

What was the original genesis? I mean, The Postmanactually started as a short story, did it not? I seem to remember reading it as a short story.

Gordon, the character in The Postman, whose name is never mentioned in the movie for some weird Costnerian reason, he’s the only character in the history of science fiction to come in second for three Hugo Awards, for short story, for novella, and for novel. But, yeah, it was a short story first and it was just about, you know, my thinking, pondering, what would I do under this circumstance? And I’m afraid my conclusion was that my biggest talent is creating delusions so that I had the character create a delusion. He’s ashamed of it, but ironically, because I love irony, he winds up doing far more good than harm.

Now the next one you wanted to talk about Kiln People. What was the genesis for that? You should perhaps explain what the story’s about, too.

Well, you know, it’s about being able to make copies of yourself. And that’s very simple. Not clones, because clones are living humans. An identical twin is a clone, and so, they have rights, you know, they’re gonna live for 80, 90 years, they should have their right to their own destiny, their own thoughts, but, no, this is a machine where you can put a cheap clay golem blank of yourself. It’s inspired by the legend of the clay golem of Prague or the clay terracotta soldiers of China of Xi’an or Adam being made from clay. In this world you have a freezer, it has a bunch of these clay blanks, and you put one in your home kiln and you put your head between these receivers, and you can imprint your soul and memory into this clay copy that lasts for 24 hours. It’s going to dissolve at the end of 24 hours, but if it makes it home from this day that you send it out on errands and things then it’ll download its memories of that day into you. And now you’ve been in two places. If you make five copies, at the end of the day you’ve been five places doing five different things. So instead of adding more life, the way a lot of science fiction does by making people immortal linearly, instead you get more life in parallel. And the genesis of this, you asked the question, is that it’s a cry for help from a busy person.

I was going to say it sounds like something a busy writer would really think was a great idea.

Almost any busy person would love to be able to make a copy. That copy doesn’t even have to be told what to do because it remembers what you were thinking just before you made it. It gets off the machine and looks down and it says, “Aw, man, I’m the green one today.” Well, it knows what to do. it has to go and clear the gutters, you know, and unclog the toilet. Meanwhile, the expensive grey model that you made goes off to the library, or you know does the research, because that model doesn’t have any sexual organs. It doesn’t have distractions.

The novel is a detective story. The detective makes four copies of himself at the beginning of this day and sends them out and he goes out himself in his original body, which you’re not supposed to do if you’re a detective because, you know, you could get killed, but all five of them go out, and what’s choice about this is you know some of them are going to die. You know some of them are going to get really, really destroyed. And so, unlike your typical detective story, there’s not this little voice at the back of your head saying, “It’s all right, it’s all right, he’s going to succeed, he’s going to live, they’ll pull him out, they can’t kill the main character. No. And it’s a great example of the ticking clock, which has been used in a great many movies and detective stories. And that is, you know that the detective has to get things done within 24 hours or the bomb in his neck will explode, you know, like in Escape from New Yorkor, you know, he has to get the antidote to the disease within 24 hours. Well, in this case, if you don’t make it home to download your memories in 24 hours you’re automatically gone. You’re just going to dissolve.

So, it was fun stuff and it led to…people should be warned that there are some puns. People have called it my most fun book since my third novel, The Practice Effect.

Well, it was one of my favorites for sure.

Well, I’m glad. And there’s a lot of movie interest that comes and goes. With Hollywood you never get your hopes up. You wait until there’s a check to cash.

This idea of downloadable consciousness in whatever form does pop up in science fiction, I know, for example, Rob Sawyer’s book Mind Scanwas about downloading consciousness into an artificial body and sending the original body off to die on the far side of the moon, but then the original body got cured, and, you know, who has the rights and all that. But do you think that’s actually ever going to be feasible, that we will be able to do that download consciousness into any form of artificial body?

Well, in a sense that’s what the teleporter on Star Trekis, only, it deals with some of the problems by destroying the original body. So, Dr. McCoy is right to be creeped out. I don’t know—how would I know?—you know, I am all the time giving talks about artificial intelligence—I just gave one on AI in defense at the Naval Postgraduate School, the same day that I gave one on AI and software security at VMware. This is one of the things that’s been slowing down my fiction writing has been a lot of public speaking about the future because people are very concerned and they want sort of out-of-the-box, you know, outside-the-envelope looks at what might be coming in them, and that’s my specialty. But the notion of whether or not we’ll be able to make AI…one of the six approaches is to copy a human brain. And if that happened and you were able to copy a human brain, well, then, you’d have this person in software. And Robin Hanson has a non-fiction—well, it’s actually fiction, but it’s written as nonfiction—book called The Age of Em, which talks about what the economy would be like if you could fill, you know, giant computers with emulated real human beings and what some of the results would be.

So, you know, all we can do is explore some of the consequences in advance. That’s what science fiction is about. And so, one of the things we did at the Arthur C. Clarke Center for Human Imagination (if you live in the San Diego area be sure and get on the mailing list) is we’ve created something called TASAT. It stands for “there’s a story about that.” It’s an attempt to get the group memory of science fiction readers engaged in this business of helping navigate the future. There’s a vast, vast number of gedanken experiments, or what Einstein called thought experiments, in science fiction—what if this, what if that—-and almost none of them are available to policymakers. I give speeches, you know, at the CIA and places like that, and very few of them have access to just this group-mind history of thought experiments. Like, for instance, let’s say that one day mole people come out of the earth. With TASAT, government officials or corporations or whatever could go to the TASAT site and say, “Hey, group mind out there, you nerds, are there any stories about mole people?” and get an instant access to what’s out there, what’s in our past, and at least have those thought experiments available to have a glimpse. You know, what if we meet aliens and they are total libertarian individualists with no concept of nations. That’s what I portray in my Mars invasion story, “Mars Opposition,” which you can find in my third short story collection, called Insistence of Vision (notice how I worked in a plug there).

Very good.

So, I urge your listeners to give TASAT a look, maybe a tickler to check in once a month to the discussions, because someday you might save humanity just by pointing out a story, because here’s the deal about a science fiction story. If it’s a first-contact story or something like that, the thing is, the people who are making first contact have reason to think that it’s about X, but it’s not a story unless it’s actually about Y. So, most stories about first contact are about how the first thing that you think is wrong and that’s exactly the kind of thing you want. A government commission that’s looking into something weird, that’s the first thing you want them to read, is ways in which they might be making a mistake. So that’s tasat.ucd.edu, and Ed will have it conveniently available along with my Web site and some links on his page.

I will indeed. Now speaking of stories from science fiction the other thing that you wanted to mention wasFoundation’s Triumphwhich was a continuation of Isaac Asimov’s Foundationseries, and it was part of a trilogy (and I thought this was interesting): Gregory Benford wrote Foundation’s Fear, Greg Baer wrote Foundation in Chaos, and I think you’re lucky to have gotten the gig since although your last name starts with B your first name is not Greg.

We’re known as the “killer Bs” of science fiction. We invited Stephen Baxter in, and if you’re drunk, you can include Vernor Vinge. The thing is that we did what’s called the Second Foundation Trilogyand Janet Asimov was so happy with it that she retired the series. Now, the novels can be read separately. Greg Benford’s is the least like an Asimov book but has some fun stuff. Greg Bear’s is very much like an Asimov murder mystery. In my case, since I did the cleanup in Foundation’s Triumph, I felt it was my job to tie up Isaac’s loose ends. So, I read just about everything, including ancient things like The Stars Like Dustand Pebble in the Skyand Caves of Steel.

They don’t seem that ancient to me. I remember reading them!

Well, they’re wonderful books from the 1940s, but since they are officially part of his canon, I wove in everything. You can readFoundation’s Triumphby itself, but I tied together…I looked very carefully at where he was going in the last years of his life with his fiction, and it came to me that he was planning to go full circle. He was planning to pull things around full circle back to the very first book, Foundation. So, I deal with the last three weeks of Hari Seldon’s life, after the Foundation is already launched and nobody really needs him anymore. He winds up sniffing a clue to something and, a frail old man in a wheelchair, an anti-gravity chair, he winds up going on the greatest adventure of his life.

I remember reading, I think it was probably in Opus 100, Asimov’s first autobiographical book, that he had sort of stopped working on Foundationafter a while because he found the necessity of going back and rereading everything and trying to be consistent was a huge challenge, and then that’s pretty much what you had to do in this case. Was it a huge challenge?

Well, yeah, but it’s very strange. I never had a very good memory for mathematical equations, but I have always had a great memory for stories. So, you know, it wasn’t that hard.

But I wanted to have your audience have a little bit of a…now, it’s interesting, some of them are thinking, you know, why hasn’t he mentioned the Upliftseries, because if it weren’t for The Postmanthat would be by far my most famous series, and the one that I owe people, and I’m hoping to really get back to moving along on the long-awaited conclusion novel in that series. That’s the one about a universe in which sapient races like humanity create new sapient races by genetically altering them. And so, we alter dolphins and chimpanzees to give them a hand, to give them a leg up, so to speak, and help them to become fully assertive sapient species. That includes Startide Risingand The Uplift War. I suppose I should mention both of those won the Hugo Award.

Oh, a person who was just at our house the other day was Liu Cixin, the Chinese author of The Three-Body Problem, which won the Hugo two years ago. He was down for an event at the Clarke Center.

Now, what’s your actual writing process like? Do you do a detailed outline ahead of time or how much of it happens through the process itself? What is that like for you?

Yes. (Laughs.) I have written from outlines and it’s been very successful. I’ve been very happy with the effects and I just can’t do it very often. What happens is I usually just dive into a book and the characters start telling me what’s going on and then I jump up and down and I go, “Oo! Oo! Oo! Oo!,” and I just thought of this and I just saw that, and this is especially true in my most rigorous and most meticulous books, which you would think had been outlined. Those would be my near-future projections, the books I wrote for grown-ups, called EarthandExistence.

If you if you want to have fun in three minutes with your clothes on, go to my website and go to the novel Existenceand click on the three-minute video trailer with gorgeous artwork by Patrick Farley. It’s really three incredible minutes, but it talks about the central topic: what if we have contact with alien civilizations that are all dead, but they have sent out these crystals with embedded beings in them, embedded emulated versions of themselves, and we find that our solar system is filled with these crystals and they don’t all agree with each other and they can’t do anything to us. I mean, they are software entities inside crystal, except they can mess with our heads and that’s the most dangerous thing of all. And then there’s the earlier novel,Earth, for which my fans keep a Wiki tracking the predictions. There were a few scary on-targets.

Both of those were not outlined in great detail, they just kind of developed?

I was trying to do Stand on Zanzibarby John Brunner, because that’s such a wonderful, wonderful book. What he did was he took the future and he made it come alive, partly through glimpses of the world of 2018. It turns out we’re living in the world now that he predicted in in 1968 and so much of it came true. He had a President Obomi. Now a lot of people are saying he predicted President Obama as president of the United States. No. That was president of a small African country, but it’s still creepy.

Well, once you’ve got the draft, especially the ones that you’re not writing from an outline, do you find you do a lot of rewriting or do you kind of do a rolling rewrite where you’re keeping everything clean and consistent along the way?

It’s the latter. I write maybe the first 20 percent of the book, and then I circulate it. I have massive numbers of pre-readers because I live by what I recommended and that is get the criticism and find out where people were confused, where they were even able to put the book down. And I’ll tighten that scene.

Then I’ll do a rewrite on that first 20 percent of the book and then I’ll write another 20 percent. And now I really know what the book is about, so after getting some more circulated feedback I rewrite that 40 percent and then write another 20 percent. And now I really know what the book is about. So, I get feedback and I rewrite that first 60 percent and add another 20. It’s a way that works for me, and as a result I deal with my weakness, and my weaknesses is the beginnings. I don’t need a lot of work in the ends. I really know how to how to end stories. I seldom need any rewrite at that point, and I should have collaborated with Robert Heinlein, because it’s the exact opposite problem. He knew how to begin a story fantastically. The first half of his novels are wonderful and it’s the second halves that kind of fall apart.

But if I have one thing to say to would-be writers, it’s to remember what your relationship with the reader is and it is a sadomasochistic one, and I’m only 90 percent joking. Your job is to create a situation in which the reader cannot put the book down, in which the reader will be late for work, will miss a report, will forget to feed the cat, forget to feed her children. A sultry voice over the reader’s shoulder says, “Honey, coming to bed?” and he just waves her away, causing stress in marriages. That’s your job. If you do that, the highest compliment somebody can say to you when they meet you is, “Damn you, damn you, I almost lost my job because of you.” You get a little chill up your spine and you say, “Thank you!”

So that’s what I meant by it being a sadomasochistic relationship. Right now, you’re the masochist side. You want to look for good stuff that’ll do that to you. And may I recommend my books. I generally I’m pretty good at that. But if you’re going to be a writer, your job is to cause those problems in other people. And if you do, I guarantee they’ll buy your next book. Especially when they find out who done it, you know, two thirds, three quarters of the way into the book, you want them to slap their heads and say, “Oh, it was all there but I never noticed it!” The reader wants to hate himself. Because every aspect of the story was all there, there were hints, there were clues, but he just barely missed them. You want the reader to be so exasperated that she tears the book in half, throws it out the window, and dives after it. That’s what you’re trying to achieve. And the only way to achieve that is by learning the tricks.

And I mentioned Heinlein…one way to do it is to retype the opening lines because your book will never be read out of the slush pile for all of its brilliant ideas, on the basis of your outline. Forget the outline. It’s the first line that gets them to read the first paragraph. If the first paragraph is great, they’ll read the first page. If they read the first page and they think that’s great stuff, they’ll read the first chapter. And even if the rest of the book sucks, you’ll get a personal letter.

So, find someone whose opening for a book really grabbed you and retype it. Don’t just read it, because you have to understand that writing fiction is the last and greatest of all forms of magic. It uses incantations to create subjective realities in the victim’s—I mean, the subject’s, I mean, the reader’s—head. If you do it well the incantation will cause a magical spell to happen in which you experience the conversation. You aren’t reading it. The little black squiggles on the page disappear.

You all have experienced this. The little black squiggles disappear because the incantation that you are unrolling is causing star-spanning explosions, deep human insights, kissy-kissy love-love. If you just read an expert section by an expert writer that you enjoyed the incantation is just gonna work again and you won’t see how they did it. But if you retype that scene, then you’ll understand how conversation is done by a master, or how action is done by a master, how scene description is done by a master, or, most important of all, how an opening works. So that’s my biggest advice to would-be writers out there: find a section that really moved you that you’d like to know how the author did that and retype it, because it’ll go through a different part of your brain than if you read it.

Good advice. And we are running just about out of time here…so, what are you working and focusing on now, on the writing side?

I just had my third short-story collection, called Insistence of Vision. I’m very proud of all three of the collections, the others are Othernessand The River of Time. I think that short fiction is one of the greatest parts of science fiction. Science fiction kept the English-language short story alive. I think people would enjoy that. I’m working on a sequel to Startide Risingbut I really need to focus more because I wind up spending just way too much time on public speaking and interviews. Oops.

Sorry about that! And finally, where can people find you online?

Oh, well, there’s davidbrin.com. I have a blog called Contrary Brin that’s ornery and contrary and has the oldest and best commentary community down in comments on the Web. Let’s see now…and Ed will post a number of links, like for instance to my speech about AI that made some surprising predictions at World of Watson a couple of years ago.

I guess I will.

All right.

Well, thank you very much, David, I really appreciate it.

Sure thing. And best of luck to all of you out there. Write well, but above all, fight for a science fictional, open-minded scientific civilization.

Excellent advice. Thanks, David.