Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

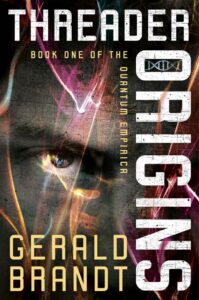

An hour-long interview with Gerald Brandt, bestselling author of the San Angeles science-fiction series and the new Quantum Empirica series that began with Threader Origins, all published by DAW Books.

Website

www.geraldbrandt.com

Facebook

@authorgeraldbrandt

Twitter

@GeraldBrandt

The Introduction

Gerald Brandt is an internationally bestselling author of science fiction and fantasy. His current novel is Threader Origins, published by DAW Books, the first book in the Quantum Empirica trilogy that will continue with Threader War and Threader God.

His first novel, The Courier, Book 1 in the San Angeles series, was listed by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation as one of the ten Canadian science fiction books you need to read and was a finalist for the prestigious Aurora Award. Both The Courier and its sequel, The Operative, appeared on the Locus Bestsellers List.

By day, Gerald is an IT professional specializing in virtualization. In his limited spare time, he enjoys riding his motorcycle, rock climbing, camping, and spending time with his family. He lives in Winnipeg with his wife, Marnie, and their two sons, Jared and Ryan.

The (Lightly Edited) Transcript

Hi, Gerald.

Hey, Ed. How are you?

I’m good. Now, we’ve known each other for quite some time now. Winnipeg and Regina are not that far apart. And we’ve showed up at the same conventions, and now we share a publisher, DAW Books.

We do. I think we first met, probably, at World Fantasy in Calgary, would have been the first time.

Yeah, that sounds about right. And I guess we share an editor, too, Sheila E. Gilbert at DAW Books.

Hugo Award-winning editor.

Oh, yes. Must mention that. Yes. And the other fun fact is that I was there in Washington, DC, at World Fantasy when you sold that first novel to DAW. And I think I was one of the first people to know about it, actually, outside of probably your family.

You may have been, actually. Yeah. That whole day is still a fog. I can’t remember all the finer details.

It was great. Well, let’s start by finding out how you got interested in writing science fiction and fantasy. Let’s take you back first to a little bit of biographical information. Did you grow up in Winnipeg? Have you always been a Winnipegger? Tell me your life story.

Yeah, I did grow up in Winnipeg, although I wasn’t born here. I was born in Berlin, Germany. So, I’m a first-generation immigrant to Canada. But I guess we moved when I was two years old. So, yeah. I don’t remember much of my first two years of my life, but so, yeah, Winnipeg has been my home for pretty much my entire life.

So, growing up in Winnipeg, when did you discover that you liked science fiction?

You know, this is going to sound cliché, and I’m sure that just about everybody you have spoken to has said the same thing, but I started out as an avid reader. Don’t we all?

Pretty much, yeah.

And the books that grabbed my attention, although I read pretty much everything, you know, if you handed me a ketchup bottle, I’d read the ingredients list just to read something . . .

And then do it again in French, since we live in Canada.

Well, no, I . . .no, no. I’m sadly a one language person.t I did not do well in school in French classes. But anyway, so yeah, the books that really seemed to draw me more than anything else were, well, mainly fantasy novels, and science fiction as well. So, yeah.

Do you remember any specific titles that had an impact on you?

Oh, my gosh. You know, the Foundation series, Asimov’s Foundation series, was a big one for me, going a ways back in my younger, younger years. Piers Anthony was a big one for me, but I find myself struggling to . . .I went back and read some of him recently, and I don’t think his books aged that well, unfortunately.

No, I loved them too. And I had kind of the same reaction when I looked back at them.

Yeah, yeah, yeah. So, what else? Wow. Yeah. You’re asking me to go way back. You know, I’m pretty old.

Oh, yeah, look who’s talking to me. I’m older than you are. So, you know, I can remember. I’m sure you can.

Well, I . . . you know, maybe . . . but I don’t even have many of those books on my shelf anymore. You know, I’ve gone past what really got me into the genre, I think.

Well, when did you start writing? I read in another interview, I think, that you did some in junior high?

Yeah, in junior high. I wrote . . . I started thinking that, you know, I’ve been reading all this stuff, I can start writing it. And it was much like the poetry I was writing at the time, rather angst-filled teenage garbage, but, you know, I guess we all start somewhere.

How much did you do? Like, were you writing long things or short stories or . . .?

Yeah, short stories. I didn’t even know they really existed back then. So, I was reading novels, you know, I was reading Stephen R. Donaldson and things like that. So, I was basically copying what I read. And, you know, I got well into some novels, but I never actually got anything finished back then. I think I actually still have a notebook here somewhere that has a really bad hundred pages of a handwritten fantasy novel in it, which I really should get rid of before I die because somebody will read it, and that would just be bad.

I have actually, right here on my desk, I have the handwritten manuscript of my first novel that I wrote when I was fourteen.

Oh, boy.

And it was typed up later. And you never know, I might put it online sometime under a pseudonym or something. And my worry is that it will sell better than my actual novels.

Well, you are a braver soul than I.

I don’t know. I haven’t done that yet. I’ve talked about it for a long time, but it hasn’t happened yet.

OK.

So, I also read in that interview, though, that you kind of . . . well, first before I do that, did you share your writing with people at the time? I always ask people that about their youthful writings. Were they brave enough to share it, or was it a thing you just kept to yourself?

Never. I did not share any of my writing until I got serious, quite serious, about it when I turned forty. And even then, I held off for a number of years before I thought I was good enough to have somebody else look at.

So, there was a gap in there between writing in junior high and getting serious about it.

There was.

What happened in there?

Well, in Grade 10, so, the first grade of high school, they offered a computer programming course. And on a whim, I took it. And that was the end of my world. I started, at that point, I started a career of computer programming. And I’m glad I did. It did very well for me. I’m actually not programming anymore, I’ve gone more to the IT side now, but it gave me a career that helped me, you know, let me raise a family and buy a house and do all those things that normal people do that you can’t do for, in most cases, you can’t do with a writing career.

I did programming briefly. I didn’t have a class in it, but I learned Basic, and I had a Commodore 64, and I wrote this extensive program using the Commodore 64 music chip that allowed me to input sheet music into it after a fashion. And I did that, and it took hours and hours, and it worked, after a fashion. And then when it was done, I thought, “You know, there are other people who are better at this than I am.” And I was never tempted to be a programmer after that. So I had a different reaction to you, I think.

Yeah, yeah. M first introduction in high school would have been punch cards and programming in COBOL before we moved on to the Commodore PET, which was the first microcomputer I touched. So, that was a long time ago.

I did take one programming class. I lied. I took an off-campus university programming class, and it used a Commodore PET, as well. So there something we have in common. But then you did something with it, and I never did. So, what brought you back to writing then? I mean, were you continuing to read science fiction through all those years?

Oh, absolutely. My reading has never . . . well, I’m not going to say never. My reading did not drop off at all during those years. That has changed since I’ve become a writer because I just don’t have as much time as I used to have. But yeah, I absolutely kept on writing or kept on reading, and yeah, I wouldn’t have stopped. Nothing would have stopped me from reading.

I kind of loved science fiction and fantasy together, but your writing is certainly, so far at least, more on the science fiction side. Were you more of a science fiction reader than a fantasy reader, or were you indiscriminate?

I was more of a fantasy reader than science fiction, and everything that I’ve ever written before my first sale has been fantasy, but I have never sold any of my fantasy. I’ve only sold my science fiction. So, go figure.

Hmmm. Well, how did the switch to writing seriously come about? What made you decide at the age of forty or whenever to take it seriously and really get into it?

Yeah. You know, it was always there. I mean, always the idea that, you know, I’m reading this stuff and I can do this. I want to do this. But at forty, a little bit before forty, I became a stay-at-home parent to my two boys. One was in Grade 1, and the other one hadn’t yet started preschool, I guess, so he was home all the time. And one of the parents of another kid in my son’s, in the Grade 1 class, she was a writer. And, you know, we started talking a little bit, and I just kind of woke up one morning and said, “This is it. It’s now or never. I’m forty years old. If I don’t start writing, then I probably won’t.” So, I gave myself a goal. I said, I will have something published. A novel was my goal. I will have a novel published in ten years. Or if I don’t, I’ll stop because it’s obsolete. Ten years to me was the perfect amount of time to hone whatever skills I might have had and churn out something that was publishable. And the end result was Sheila offering me a contract at roughly ten years and three months.

So close!

And at that point, you know, I wasn’t going to stop anyways because ten years of actually struggling and getting better and writing and being critiqued and critiquing, I wasn’t going to stop at fifty, at any rate. I was going to keep on going until I had something sold. But, you know, it’s interesting that it happened roughly in the time frame that I gave myself.

Well, did it just sell out of the gate, or was there some back and forth with Sheila on that particular novel?

Well, there’s a five-year story.

Yeah, I kind of knew it was there. That’s why I asked.

Yeah, I figured you did. Actually, Sheila came to the convention, KeyCon, here in Winnipeg.

Yeah, I remember. I was there too.

So, we did meet then before World Fantasy. I guess we never spoke.

Yeah. We probably didn’t notice each other.

Probably not. No. But anyway, as a big surprise to her, KeyCon had set up a pitch session, which she . . .

I remember that!

. . . . which she was not prepared for. So, I signed up for the pitch session, and it was my first pitch session ever. And it took me by surprise, probably almost as much as it took Sheila by surprise. They put thirty of us into a room with Sheila, and we all pitched to her in front of each other, which is not actually the way it works, really. But whatever, it happened.

I, unfortunately, followed somebody who had had a lot to drink the night before and showed up with bathroom-tile imprints still on the side of their face. And they tried to pitch to Sheila and finally just stood up and said, “I’m sorry, I can’t do this,” and walked out. And then they called me. So, I went up to the desk and, you know, did the brief introductions, and she said, “What do you have?” And I stuttered and stuttered. And I said, you know, “I’m really quite nervous. And I’m not sure that I can remember what I memorized anymore.” And she said, “Well, do you have it written down?” And I said, “Yeah, it’s right here.” And she looked me in the eye, and she said, “Oh, thank goodness.” And she took the paper, and she read it, and she requested a full.

And then, I guess, we met, that’s why I started going to World Fantasies, probably. We met at every World Fantasy after that and talked about the book. And, you know, she never actually had read it yet, but she asked me what I was working on, what was new, what was coming up to me. I guess she was kind of just pushing me to make sure that I was serious about the work. But writing this was what I wanted to do. You know, in the meantime, I pitched other books to her, and she kind of grimaced once or twice. Threader Origins was one of those. But I wrote it anyways, despite her grimace. And then, you know, we’d meet, and she said, “You know, I managed to read your synopsis on the airplane. So, we’re going to talk about your synopsis rather than The Courier.” And so, she critiqued and poked holes in that. And I kept saying, “Well, you know, this is what happens.” And, you know, so I answered all of her questions on that. In the next year, she actually read it and bought it. But it was a five-year process.

That’s an interesting initial sale. I remember . . . because I was at KeyCon, I was working on Magebaneat the time, which is by one of my pseudonyms, Lee Arthur Chane. And I remember, I actually remember after she had finished her editorial comments on that, saying to her on the elevator, “But I can write, can’t I?”

When she bought The Courier, I left our little meeting, and we arranged to meet later on in the day again. So, I went up to my room, and I phoned the wife, and she actually left a meeting to take my phone call. And she went back into the meeting, and she says, “My husband just sold his first novel.” And everybody in the meeting, including her boss, looked at her and said, “Well, you’re not quitting your job, are you?” So luckily, she said no, because the writing . . . but anyway, in that same convention, Sheila and I sat down in a quiet spot, and she gave me my first editorial on the novel at that convention. And I kind of felt like garbage because I didn’t know how things worked. But yes, the same as, you know, “I can still write? You think I can still write, right?” And then, about twenty minutes after she gave that first editorial pass, I went to my first DAW dinner.

Oh, yeah. It’s, I mean, I’ve said that to Sheila, it’s been well, you know, “I bought the book, so obviously I think you can write.”

Yeah. I think Julie Czerneda has asked her to at least say something good right at the beginning so that we actually start off thinking, “OK, maybe it’s not that bad.”

Well, we’re going to talk about the editorial process at the end of this next bit because that is part of the whole published-author thing that people are interested in. But let’s talk about now how . . . well we’ll focus on the new one, Threader Origins, which just came out as we’re recording this and will have been out for a month or so when this goes live, and use that as an example, tell me—the classic question—where do you get your ideas? Or, if you prefer, what was the seed for this particular novel? How did this particular one come along, and how does that tie into the way that ideas normally bubble up for you?

Well, this is my second series with DAW, and—although I have a bunch of trunk novels, so I guess I have experience there as well—but normally, as is the case for this one, I have a character . . .

Before we do that.

Yes?

Very important. Give us a synopsis so that people know what we’re talking about.

The dreaded synopsis, how writers dislike that part. But Threader Origins is an alternate-Earth book. Darwin Lloyd is a university student. He’s going to become a physicist, and he loves quantum theories and all that stuff. And he’s following in his father’s footsteps. So, he gets an internship where his dad works, and together with, of course, the whole team, they build a machine that can basically generate unlimited electricity to power whatever you want, a whole city or whatever. And Darwin is there for the very first test where they go up to 100 percent, and things go wrong, and he gets pulled into an alternate earth by the machine. And then things go bad from there. In the world he gets pulled into, the same machine was turned on five years prior. So, they’ve had five years of this machine generating what the people call threads. And, you know, they can . . . it can not only, not quite alter reality, but it can kind of predict the future. And it can do various things. I won’t get into too much detail here. And he sees how much it’s destroyed the world he’s gone into. And his main goal is to get home and turn the machine off. And of course, nobody knows how to do that, get home or turn the machine off. So, it’s a struggle.

The overall story is called the Quantum Empirica, correct?

Yes.

Yes. Now, go back to where did this one come from?

All right. We’ll go back to, again, Darwin Lloyd. He just kind of popped into my head one day as not quite a fully formed character, but pretty close. And I fleshed him out and figured out what his flaws were, what happened to him before the book started. And I figured I had a great character to build a novel around. So, it took me quite a while to figure out what kind of world to throw him in that would test him the most. And yeah, once I did that, I just started researching and writing.

Well, what does your planning and outlining process look like? I read a description of it, and it sounds quite . . . what’s the word . . . physical. Post-it notes and things like that. So how does that work for you?

All right. Yeah, I have . . . I bought a four-by-eight metal whiteboard at IKEA, and I have so many stacks of Post-it notes around here it’s ridiculous. But basically, what I do is . . . by the time I’m into the Post-it note stage, I already have my main character, and I have the majority of my world thought out, not necessarily detailed, but thought out. And I might have a couple of secondary characters. And I grab my Post-it notes and I write . . . sometimes it’s as little as one word, and sometimes it’s a sentence. And I take that, and I stick it on the board. And basically, that Post-it note becomes a scene, and sometimes the one word is an emotion, right? I know that at this point, there’s got to be a lot of pain and hurt. So that’s what I’ll put in there, because I don’t know what scene is going to bring that out yet, the details, but I know that I need it, so I’ll put it on there. And by the time I’m done, I have anywhere from 75 to 100 Post-it notes or more on my whiteboard. And it’s possible that they’re all different colors because I assign a color per point of view character. So, for example, on the San Angeles series, I probably had about six colors on my whiteboard. For Threader Origins, it’s just all Darwin Lloyd’s point of view. So, it’s all one color. In this case, it’s pink. I’m still staring at it now for book three.

And yeah, I take it, once I have all my Post-it notes written, I arrange them to make more sense. And so, I know where I have my highs, I have my lows. I don’t know chapter breaks or anything at that point yet, but I actually do my initial rough plot on that whiteboard. Once I’m sure that I have something that I like that is somewhat coherent, I take all of those notes and put them into a spreadsheet and, again, color-coded based on character point of view. And that’s where I start expanding things. You know, if for, like, for the San Angelesseries, every scene had a timestamp. So, I made sure that the timestamps matched for every point of view character, and all that stuff. For Threader Origins, I had separate color coding for the threads that Darwin was learning at a time because the colors of threads have specific meaning in the novel.

So, I fill all that in, and I take those one-word or those one-sentence scenes, and I put them into three or four sentences in the spreadsheet, and I just build it and rearrange it until, again, I’m happy with it. And then, I take the somewhat detailed description of three or four sentences, move those into a document and start writing from there. I usually end up with . . . by the time it’s all said and done, seventy-two to seventy-five scenes because I average thirteen to fourteen hundred words per scene, and that gets me a 100,000-word novel.

Wow. Not the way I work!

And you know, the thing is that none of what I’ve done up to this point is written in stone, which is good because, as you know, as you’re writing, these things just organically kind of grow. I don’t leave, at least for the first half, I don’t normally leave my plot. But there’s these little details that come in. This little, this character that you have to throw in there in order to show something becomes a little bit more important. So, you know that they’re going to be coming back in the book a bit more. So usually at the halfway point, I go through the process again for the second half of the book because things have changed enough that the second half of the plot, although it’s, the plot is probably OK, it’s the details of the interactions and the emotions that might have changed. So, I go back at the half unit, the halfway point, and rearrange that second part of the plot.

So, this Post-it approach, how did you decide to use that approach? Does that somehow relate to being a computer programmer and the way that you plan out when you’re reprogramming, or . . .?

No, not even . . . not at all, actually. You know, when you’re starting out, and again, during that time period when I wasn’t writing, but, you know, and I was doing all the computer stuff, I’d still buy all these books on how to plot and character development and all this kind of stuff. My bookshelf is filled with them. But the thing that made sense to me was . . . people were always using note cards, right? They’re saying you take your, take the note cards, and you write things down in the note cards, and that lets you rearrange things, and I tried it, and it didn’t work for me, but, you know, and then I moved to Post-it notes and just seeing it visually on the whiteboard all at once worked for me a lot better than having a stack of note cards that I would rearrange or have to lay down on the floor to look at the sequence of events. And then, at the end of that, I have to clean it up because, of course, I have kids in the family, and I can’t leave stuff like that on the floor. So, it just kind of a progression of the note cards just into Post-it notes.

“Your novel doesn’t make a lot of sense.” “Yeah, well, the cat ran through it at just the right moment.”

Exactly.

You know, it’s . . . you know, I read all that stuff, too, in the magazines, and yet it never, never took with me at all. So, I’m always interested in . . . you know, part of the point of this whole podcast is that everybody does it differently. So, it’s always interesting. So, once you start writing, it’s sequential because you figured it all out ahead of time. What’s your actual writing process? I know, for example, that you use rather different word processing software than most people do.

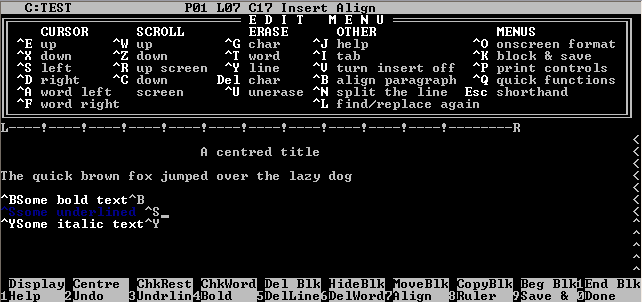

I do. I use . . . you know, I tell the world I use WordStar, which is a 1980s word processor. But, you know, having been a computer programmer for too many years to even consider, I wrote my own word processor, and I use that, and it’s WordStar compatible.

And what is your actual . . . well, first of all, what do you like about that? What were you looking for that made you do that?

Well, the first thing is that the muscle memory of just how to use WordStar, because I used it, like, in the ’80s and early ’90s, I used it for all of my other stuff, whether I was documenting or whatever, I was doing some code or whatever, I used WordStar. So, the muscle memory was certainly there. But it’s really a writer’s word processor. You know, I can . . . if you have Microsoft Word, if you highlight a block of text and you know you want to copy that somewhere, you want to do something with that text, but you’re not quite sure, and then you go and do something else, that block of text is not highlighted anymore. So, you kind of lose what you’ve highlighted with WordStar. I can highlight a block of text, and then I can write for six hours, and I could say, oh, that block of text belongs here, and boom, I can copy it. And it’s still highlighted. So, it remembers things like that. It also has bookmarks. It has ten bookmarks. So I can, say, remember this position in the document as bookmark one or whatever, and then if I’m writing and go, “OK, I have to remember,” I go back to bookmark one, and it’s one keypress, and I’m back at bookmark one, and I can go in, then I can go back to where I was writing. So, it’s easier to jump around. It’s almost like you have a printed document with your fingers in between pages, and you’re flipping between chunks of document to make sure things flow. It just seems to work better for me.

Well, when you’re writing, do you . . . where do you write? You just . . . and how do you find the time for it? You do have a full-time job. So how do you juggle all that?

I do. I had a full-time job up to the second book in the San Angeles series, and the schedule on that was so tight that things were not working out for me. So, I actually went down to three days a week on my job, and that helped a lot. But then, of course, with this whole Covid thing going on and me being the IT guy, my workload increased because nobody’s working in the office anymore. So, I have to support these people in their homes and stuff like that. So, I’m now back to four days a week, so close to full time, but not quite. So, I got into the habit of writing at five in the morning for The Courier because I was the stay-at-home dad at that point, and my kids woke up at seven. So that gave me gave a two-hour block when nobody was awake. I could just come into my office and sit down and write.

Over time that has kind of disappeared. And I started writing in the evenings, and . . . because the kids got older and whatever, I started writing in the evenings and on weekends. For the current book I’m writing, which is the third in the Quantum Empirica series, I tried dictating, which worked for a while. But I’ve now gone back to five in the morning writing because it just seems that I’m more creative at that time. I try to get up at five in the morning, try still being the keyword, and write for a couple of hours before the whole house wakes up.

Are you a fast writer or a slow writer?

Depends on what I’m writing. If I’m writing an action scene or something with a bunch of dialogue, I can turn that out pretty quick. If I’m writing something, you know, in between those two, where a character has to get from A to B and stuff like that, I struggle with those ones. And those, you know, if I get 200 words, 200 words, 600 words in those two hours, I’m happy. But if I’m, like, I’m doing action scenes, I can do 3,000 words in those two hours easily.

So, once you have a first draft, what does your revision process look like? But what things do you do on the and yeah, how many passes do you make and all that sort of stuff?

How many passes I make is, you know, anywhere from, well, double digits. Let’s just go double digits. Leave it at that.

It’s hard to tell when you’re working, it’s kind of an organic thing, really what you count as a pass.

It is, although I do have fixed passes in there as well. I do have a specific pass where I, I add description because when I do my first draft, I’m not a descriptive writer. My first draft could be anywhere from sixty-five to seventy-five thousand words, which is not the right size for a novel. It’s too small. And I will say one of the passes is adding the description so that you can actually get to know where you are in the book when you’re reading it. And another pass I add I use specifically for emotional content to make sure I’m hitting those points, you know, and then I have the technical passes as well, you know, don’t use passive voice and all that kind of stuff, so . . . But then there are the organic passes where you’re just kind of going through it, and it’s tough to keep track of. But I don’t revise as I’m doing that first draft. I don’t go back ever. I get the words out because I can’t fix what’s not on the paper. So, I’ve got to get that first draft out before I start any revision. So that first route, that first draft, is usually quite rough.

And how long does your revision process usually take you?

That all depends on when the contract says the book is due.

I guess I’m done revising! Yeah, I know that feeling.

Yeah, you know, that’s a tough call because it’s different for every book, really. It all depends on the details that I need to remember. For the first, the San Angeles series, every scene had a date and a time stamp. And I will never, ever, ever do that again because that is a headache. I end up using Gantt charts in order to keep track of who was where and when and what they knew, just to make sure that those timestamps were actually accurate. And, yeah, that was a struggle. So that took a lot of revision, right? So that took more time. And in this one, because it was a bit more of . . . it’s not as strict on its timelines, really, so the passes were. . . how long it takes is how long it takes, I can’t . . .I don’t think I can answer that.

Well, you did, kind of.

Well, kind of.

So what’s . . . once that deadline comes along and the book goes in, what do you find . . . well, why don’t you describe what Sheila’s editing process is for you?

All right. Before I go into that, I will say that Sheila is thankfully, thankfully happy to give you an extension if you need it. And I have used that twice now. I used it for the last book in the San Angeles series and it made me feel so bad that I swore I would never do it again. And so, I did it again on the last book in the Quantum Empirica series.

I may have taken advantage of that once or twice.

Yeah. And for this extension, I blame 2020. I take full responsibility for it, of course. But 2020 was quite hard on my creative process. So that’s why book three is late and being handed in, but it will still be, the books will still be released in a nice, timely fashion, simply because I’m ahead of the game already, right? With the first book being out and the third book being halfway done, right, I’m still, I still have time. So, things are, you know, the books will be released in good order.

But the process for dealing with Sheila, as you know . . . you read about how everybody goes, and they talk about the editorial letter and all that stuff. So, that’s what I was expecting. But that is not the way that Sheila works. As you well know, Sheila will call you up on the phone at a preplanned time, and you will be on that phone for however long it takes to for her to go through her notes. And she will go through and tell you what is wrong with your book. And it’s all verbal. It’s all done on the phone. And for my first two books, I was scribbling away so fast I might have missed half of what she said, at which point . . . because she always calls me on my cell phone, I have an app on there now that records our phone calls so that I can always go back and listen to what she’s saying again, because my notes miss things. You just can’t keep up. She’s a fast talker, and my handwriting’s not fast enough to keep up with her.

And what sorts of things are you generally, does she generally suggest you might need to expand upon or rewrite?

It’s different, I think, probably for every author, so, yeah, and I think it’s different for really every book I hand in. Right? It’s . . .I’ve never actually looked for a common thread, which is probably a weakness of mine because if there was a common thread, I should really fix it, shouldn’t I, or hand the book in?

I usually find it’s, like, you know, expanding on something that there’s just not enough information there for the reader to follow what’s going on or that sort of thing.

I would agree. It’s continuity comments or things where, yeah, there’s not enough detail to explain why the character’s going this way, or there is enough detail, and she doesn’t think that it really fits in with the character’s psyche of what she’s learned of that character and she doesn’t think it fits. I’ll take an example. The first version of Threader Origins that I handed in, the relationship between Darwin and his father was antagonistic. They did not like each other. They blamed each other for a lot of things, which I won’t get into detail with because that’s a bit spoilerish. But they butted heads a lot. They didn’t really like each other. And, you know, it created tension, and it created conflict, and it moved the book ahead, so it did its job. But when Sheila read it, she didn’t quite like it. She didn’t think that that was really what the book needed. So . . . and this is the nice thing about doing phone calls. We sat there, and we just hashed it out. We figured it out together. And she kind of tossed in ideas. And I said, you know, well, that won’t work because of and then I tossed in ideas, and she says, well, that might work. But what about, you know, we just came to something that we were both quite happy with, and that relationship changed. And because it changed, it added so much more depth to Darwin’s and the father’s character and increased the whole emotional line of the novel. It was just fantastic.

Before you were writing seriously or when you started writing seriously, did you have any fear of the editorial process? I know that some beginning writers, you know, “Well, the editor’s going to change everything, or they’re going to ruin my story.”

Way back when I didn’t even know there was an editorial process. So, no. My first experience with the editorial process would have been with Bundoran Press. When Virginia O’Dine ran Bundoran Press, Heyden Trenholm edited Blood and Water for her, and they bought a short story, my very first sale ever in 2012 maybe. So, Hayden was my first editorial process thing.

Another editor we’ve shared!

I loved working with Hayden. He was, you know . . . I expected the editorial process to be, at that point, anyways, this is wrong. This is how you can fix it. And that’s not really the way it works because the editor didn’t write the story, right? It’s my story. So, what the editor—and Hayden and Sheila will both do this—is they’ll say, “This isn’t working. What can you do to make it better? This feels a bit forced to me, or this spot feels weak, or I’m not getting the emotional hit I think I should here.” But they didn’t tell you how to fix it, right? They just tell you that it’s not working. And then you have to go back and fix it. And I think that was the biggest surprise for me. When, you know, when I first went with Hayden and when I first actually started thinking about the editorial process, is that they leave it up to you. They don’t do the changes for you, which I love.

But if you wish to consult with them about possibilities, they’re certainly willing to help out in that.

Absolutely. Absolutely. You can. And that’s what they’re there for as well, is to hash things out if you need them. As I mentioned about Sheila, she’s very, very good at that. With Hayden, I didn’t do that as much.

So, one thing I forgot to ask you about was at the point at which you have something that’s almost ready to submit, do you use beta readers of any sort, or do you have a writing group or anything like that?

I have a loose writing group. We actually used to be a critique group, but I had to bow out of that because my timelines were so tight I couldn’t read somebody else’s work and do a critique. So, I didn’t feel like I was giving in to the critique group as much as I was getting out. So, I had to pull away from that. But that group instead just became a general writing group. And we will talk and discuss ideas. You know, if I’m hitting a roadblock, you know, I’ll say, “My character’s been in this location for so bloody long, and I can’t get them out of there. What am I supposed to do?” And we’ll hash things out verbally as we meet. But it’s not a formal critique group. But I do have beta readers, for sure. I have a handful of beta readers that I trust and respect their opinion, and they get everything before I hand it in. And even then, you know, they’ll give their feedback, and one beta reader will absolutely hate a section. And every other beta reader . . . I mean, beta readers will never tell you they love a section, almost never, but they didn’t bring up the section at all, so I’ll kind of go, “OK, well, one person out of however many didn’t like it,” I’ll read it and I’ll say, “No, this is perfect for the book. I’m leaving it in as is,” or I’ll read it in context of their opinion and I’ll say, “No, he’s right. I could do this and this and this, and it would be a better scene or a better section.” But normally, if one person picks something up, it’s going, it’s not, you know, it’s not something that you’re going to change. If multiple beta readers pick up the same thing, then I don’t have a problem.

See, I’ve never, never had beta readers, still don’t have beta readers, so I always ask about them because it’s just, I’ve never been someplace where I felt I could find them. I probably could online now, of course. But when I started, I was in Weyburn, Saskatchewan. And, you know, as I’ve mentioned before on here, the writing group in Weyburn at the time consisted of elderly women who wrote stories about the Depression, and I didn’t really fit in there.

No. Yeah. I think, you know, just a couple of my beta readers are actually local. Most of them are spread far and wide. In fact, I don’t even know where two of them live. I just know they’re in the States. That’s all I know.

I was part of a writing, not online, but a by-mail critique group, for a while back in the Dark Ages, but, boy, that was a slow process.

Yeah, at the beginning, I did join an online critique group, and I think they’re actually still running because I still get some emails from them occasionally. But that was, also, I found a slow process. I can’t imagine doing it over mail. That would be a struggle.

Yeah, it was slow, but I did find a couple of really good . . . I ended up with a couple of really good people, and I guess we were sort of beta readers for each other at that point. We didn’t call it that back then. But yeah, I just never got in the habit of that. And I keep thinking . . . maybe my books would be better if I did. But, you know, I’m kind of set in my ways at this point.

You know, us old guys. We’re stubborn

Yeah. “I’ve never done it that way. I’m not going to start now.”

That’s right. Get off my lawn!

The other thing I wanted to ask you about, we talked a little bit about the characters. When you’re doing all this stuff, do you write down character sketches? Do you, you know, just sit and think about the character and try to build all the backstory and everything at that point? Or does a lot of it get discovered as you write or how does that work for you?

You know, although I do start with a fully fleshed character, I do not have a lot of their background. And I also have no idea how they look. If you read my novels, you’ll find that I almost never describe what my characters look like. I’d rather have the reader do that. And that might be because I don’t really know how they look like. I might have an image in my head, but it’s still kind of blurry. But yeah, the character, although I have a full-fleshed character when I start, I don’t know their backstory, and although I kind of know their emotional part going forward, I do that . . . yeah. I discover that as I go. It’s not part of my plotting process, not part of anything that the character develops as it goes. And then in the revision process is when I’ll go back and make sure that there’s consistency in all of that.

And the other thing I kind of forgot to ask you about, and especially this one, which is, you know, quantum, multiple universes and all that sort of stuff. What kind of research do you end up doing for most of your books?

Yeah, that . . . this is a question I really hate with the Quantum Empirica series specifically.

Sorry!

No, I also get asked that a lot because it is quantum strings and quantum theory. I ended up buying many, many books and doing a whole bunch of online research into quantum theory and quantum strings. And, yeah, and I realized, much to my chagrin, that I’m just not smart enough to know that stuff.

So, yeah, I did a bunch of research that really didn’t stick with me because I wasn’t smart enough, or intelligent enough, to keep all those details, you know, going. For the Quantum Empirica series, what really worked is, one of the books I bought was The Dancing Wu Li Masters, I don’t have the author’s name in my head right now. It’s quite an old book. But it kind of brought, you know, Eastern philosophies together with physics and kind of tried to meld them together into something that was explainable. And that really fed into Threader Origins. In fact, the title of the book was The Dancing Wu Li Masters, and I actually have dancers in Threader Origins based off of that. I had a friend, I was reading the book and going through it with a highlighter and marking pages, and a friend picked up the book and started reading my highlighted comments and threw it back on my desk in disgust. He says, “You haven’t highlighted any of the scientific stuff, just all the emotional content,” and I said, “Well, yeah, OK, that works.”

Yeah, research is, you know, because both of my series take place, you know, basically on Earth, I don’t have any extra, you know, planetary stuff. And, you know, and especially for Threader Origins, Google Maps was a big one, a big part of my research. And then I had the opportunity, actually, I went on holiday and drove through most of the areas that Threader Origins covers in the US, which also help me bring in a bunch of extra details on the scenes.

OK, well, we’re getting down to the last few minutes, so I’ll ask you the other question you’ve already said you’ll hate, which is the big philosophical questions.

Did I not mention that I’m not intelligent enough?

Before we started, you said you weren’t philosophical enough. So, we’ll see. But they’re really not difficult questions. I think the first one is, why do you write? The second one is, why do you think any of us write? Why do we tell stories? And the third one is, why do you write stories of fantastic specifically? So, in whatever order you like.

All right. Well, I will do them in the order you asked. I will ask you to rephrase those questions as well, because I will have forgotten what they were about to get them. OK, why do I write? is the first one. And a lot of people I know, a lot of authors I know, say they write because they have to. If they don’t write, they’re going to go crazy. They’re going to go insane. And that is not my answer. I write because I enjoy it. I love the creation and the development of characters and the world-building. And, you know, it’s a mental exercise that I love doing. And could I go without writing? Probably. Would I be happy about it? No, no. I enjoy the process. I really, really enjoy the process. That being said, I enjoy having written more than the actual writing as well. So, I’m a complex person. How’s that?

That’s a very common affliction of our writers.

There you go.

And the second question was, why do you think any of us write? Why do we tell stories? Why do we make stuff up? As human beings, we make. Why do we make stuff up?

I think I’ll couch that in our current times, when times get difficult and tough, you know, whether it’s Covid-19 or the politics south of our border or whatever is in the world or whatever is stressing you out or hurting you, people want and need—most people, not everybody, not everybody—but people want and need some sort of escape. And even if that escape can be as depressing or as painful as the real world, it’s an escape from where they are in their lives and where they’re at. It gives them the chance to, whether they live in your main character’s skin for a while or whatever, gives them a chance to escape from reality, you know, without the use of psychotics.

And the third question was . . . what was the third question . . .oh, why, if you’re going to tell stories for people to escape into, why make it stories of the fantastic, fantasy and science fiction?

Because it’s what I love to read, I actually . . . when I started out, I never even thought of writing a different type of book. It’s just what I love to read. It’s what I love to write. Although I also love to read thrillers. And although I’ve tossed around the idea of writing a thriller, I don’t . . . you know, by the time I’d be finished writing, the thriller would have too many fantastical things in it to be considered just a thriller.

Yeah, whenever I’ve tried to write something else, there’s always, “But if I put a ghost in here, this is really cool.”

I could put it a gryphon right here! Yeah.

So, you’ve mentioned that you are, I guess, writing the third book. The second one is in revisions, and the first one is out. So that’s what you’re working on now?

Yeah, I’m working on the third book, and again, the whole Covid year and some of the politics that have been happening have made it a struggle for me to be creative. But I am working my way through it, and I will hand this one in on its extended deadline.

And what are the titles of the second and third books?

OK, so it’s Threader Origins is the first, Threader War is the second and Threader God is the third.

And do you know roughly what the release schedule is?

I have no clue. I have not heard the release schedule on anything but the first book, which, as you said, just came out.

And do you have anything else in the works beyond that? Are you already looking beyond . . .?

I do I, I have an idea, and usually, I wake up with these ideas in the middle of the night and scribble them down on a piece of paper, and in the morning, it feels like I’m reading a doctor’s signature. So . . . and the idea is gone from my head. So what happened this time is the idea came during the day, but I was in the middle of doing writing on Threader God. So I emailed the idea to my agent, and now it’s up to her to remind me when it’s it’s time to work on it.

And you’ve got a little short fiction as well, I think, for an anthology that’s coming up?

I do. I have . . .What’s the title? It’s called Derelicts, by Zombies Need Brains. I’m one of their anchor authors. That doesn’t mean that they’ll actually buy my story if it’s garbage, but I’m hoping they enjoy it. I handed that in . . . probably December, January 1 or 2, I think, so a couple of days beyond the due date when it was due. But they will get to reading it, and I will get my editorial comments on those. And I think that book is . . .you know, I don’t have a release date on that either. But if they accept it, it’s my third short story sale.

I’m in another one that was Kickstarted at the same time. That’s why I asked. So, I turned mine in before the deadline.

Uh-huh.

Not too far from the . . .

Yeah. How’s that full-time job working for you? Sorry, that was harsh.

All right. Fair enough. Fair enough. And where can people find you online? I mentioned it off the top, but we’ll mention it again here at the end.

All right. Well, I’m geraldbrandt.com on the Web. I’m on Facebook as Gerald Brandt Author, and I’m on Twitter @GeraldBrandt.

And we should mention that’s Brandt with a D. B-R-A-N-D-T.

It is a silent D, so. Yes, yeah. If you’re not sure of the spelling, you can look at the transcript.

Exactly right. Well, thanks so much, Gerald. It’s been great chatting with you. You know, I thought about it for a long time. I have to limit the number of DAW authors I do, though. I have to space them out because I could easily do nothing but DAW authors because I’ve met so many of them at dinners and stuff.

Yeah. Yeah. Well, thank you so much for having me. This was a blast.

I had a great time, and best of luck with the trilogy, and I’m sure I’ll talk to you again soon. Or hopefully, we’ll see each other in person again soon.

That would be nice. I would . . . I can hardly wait to actually meet people again. This has dragged on long enough. But I think we’re looking at probably another six to nine months before something happens.

Yeah, probably.

World Fantasy in Montreal.

Yeah. Yeah, I hope so. Well, thanks again.

Thank you.