Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

An hour-long chat with Frank J. Fleming, author of the Superego science-fiction series and senior writer for the satire site, The Babylon Bee.

Website

www.frankjfleming.com

Twitter

@IMAO_

Frank J. Fleming’s Amazon Page

The Introduction

Frank J. Fleming is the author of the Superego series of science-fiction novels. He’s also a humor writer for the Babylon Bee, New York Post, and USA Today, and has been a scriptwriter (Love Gov).

Fleming is a Carnegie Mellon University graduate and works as an electrical and software engineer when he’s not writing. He has also been a pioneer in virtual-reality video. He lives in Austin with his wife and four kids.

The (Lightly Edited) Transcript

So, Frank, welcome to The Worldshapers.

Hey, thanks for having me.

I reached out to you because I . . . of course, I encountered you actually through the Babylon Bee. And this may not surprise you because you live in Texas, so you will know that when I say that I grew up in the Church of Christ, the Babylon Bee has humor in there that appeals to me because . . . I’m often passing along, not so much the political stuff, which is funny too, but often the church-related stuff I can pass on to people that I went to school with, I grew up with, and we all get those . . . we all get that satire.

That’s funny. I’ve thought about doing some more specific Church of Christ jokes, but I’m not sure how many people would get them.

Yeah, well, there’s a few of us, but it might not be exactly . . . it might be a bit of a niche audience, I’m afraid.

Yeah.

So, that’s kind of where I encountered you. And then I was following you on Twitter, and then I said, “Hey, you write science fiction.” And I looked that up, and it looked interesting. And I thought, “Well, that’s why I have this podcast.” So, I would reach out, and here you are.

Well, yeah, thanks. I really like talking about my fiction writing. The satire, I think, gets a lot more attention lately.

Yeah. It’s that kind of a world we’re living in at the moment.

Mm-hmm.

The other thing I didn’t know until I got your bio here was that you’re an engineer and although I am not an engineer, I am married to an engineer. So, I hang out with engineers a lot. My wife, Margaret Anne Hodges, is past president of the Association of Professional Engineers and Geoscientists of Saskatchewan.

Oh, wow.

And so, I’ve hung out with engineers a lot over the years, too.

Yeah, it’s one of my favorite topics, actually. I have lots of strong opinions on different programming languages. It just doesn’t come up as much.

We probably won’t talk much about that. All right. Well, let’s start at the very beginning. I always say that I like to take my guests back into the mists of time—I don’t know how far back that is for you; it’s getting increasingly far back for me—to find out how you got . . . well, first of all, where you grew up and went to school, all that sort of thing, but how you got interested in science fiction and how you got interested in writing, and how those two things came together. So how did that all work for you?

And it’s hard to say. You know, as far back as I can think, I’ve always wanted to do little stories. You know, it’s funny, like, I work with Ethan Nicolle, you know, who did that Axe Cop. He illustrated stories from, like, his five-year-old brother, and I’m thinking, like, same age, I would always, like, play with stuffed animals or make up stories and things. And I can think back to . . . I think when I was a teenager, I probably made my first attempt at writing a science-fiction novel. It’s just, you know, I can’t help but think of stories. You know, I didn’t have much of the writing skill back then. And I just come at it, you know, and keep coming back to it. It’s just, I also found I had a bit of a knack for writing satire, particularly political satire, and I eventually started a blog and wrote more on that. But eventually, just because it’s always been a passion, I did, I think it was 2005. I actually did Superego as a short story. I just wrote it piece by piece and completely planned it out, and it actually ended up being a bit of a hit. I think I’m a bit embarrassed by the original short-story version, but it was pretty popular at the time, and eventually, I decided I have to, you know, if something’s my passion, I have to set more time aside for it eventually. So, you know, I need to work on my fiction every day. And eventually, I started just getting up at five a.m. every morning. So, I had time to both do the humor and satire and write on, novel writing, before my regular day job. And just, you know, if you do a bit of it every day, eventually it gets done.

You mentioned that you wrote a little bit in high school when you . . . well, first of all, where did you grow up?

That’s a complicated question. High school was in New Jersey. That’s, I think, still the single place I’ve lived the most. I lived there nine years, from age nine to eighteen.

And did you have books that got you interested in reading and writing in those and those early days?

It’s funny, I was a very avid reader up until high school, and for some reason, I’m not sure why, I kind of dropped off then. I remember reading, let’s see, the Dragonlance series was one of my favorites as a kid, and, you know, I read some Michael Crichton, but at some point, I dropped off, and eventually, I just was not finding time for reading. That’s something I had to reintegrate into my life and realize, you know, as they always say, if you want to be a writer, you have to read a lot. And so, that’s now something I make a priority each day. It’s usually what I do in the morning when drinking my coffee. I find that’s a lot better a way to wake up than, like, you know, looking at the news or social media.

What are some of the authors you’re reading now?

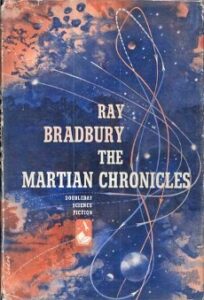

Let’s see. I actually, I just finished today, Ray Bradbury, The Martian Chronicles. I really try to alternate nonfiction and fiction. And then I try to draw from, you know, fantasy, science fiction, thrillers. You know, I try to, every once in a while, to go a little bit out of my comfort zone, just to try a lot of different authors. Lately, I’ve been enjoying Jim Butcher and is, uh . . .

Dresden Files.

Yeah, Dresden Files.

Yeah, I love those, too.

I think I’m more the style, you know, I know there’s the hard science fiction things in me, I’m more, I just I want to write something that, you know, maybe makes you think and has a few themes to it, but my main goal is just make something fun and end up . . . I really want to make a page-turner, I’d say.

Well, you went into engineering. Why did you decide to pursue that? What drew you to it?

I’ve always had a very analytical mind, and this is something . . . it feels like I have, like, two sides of me that I’ve never been able to join. I have a very creative side, a very . . . I always loved creative writing, I always loved humor. But I also, I love solving puzzles, and I just love computer programming. I love debugging. I love figuring things out. I love, especially, really complex problems where you can’t just Google the answer, and you got to be like, you know, the one go out there and solve things no one else has figured out before. And I really enjoy both. I’ve just never been able to merge the two sides.

And how did the satire writing start coming about? I mean, yeah, you said you found a knack for it, but how did you end up getting . . . I mean, you were published in some fairly major places, and you had satirical books published. How did that all come about?

Well, that, I mean, that goes back . . . I always loved humor. I think for a while as a kid . . . I almost feel embarrassed, it was like, I was like a big fan of Garfield, I wanted to be a cartoonist, and I used to write and draw comics and things. But eventually, it’s just . . .I don’t know, I played around. I found out, you know, politics is something to make fun of. We had a . . . in my high school, they had . . . a local paper was going to run editorial from a high schooler, and so, they had people submit, and I wrote a joke one about how economic and political ideas need to be tested on monkeys first before they’re tried on humans, and that got published, that was the one chosen, it got published. And then, when I was in college, I just started writing, like, joke columns. You know, I’d say I’d been influenced by, like, Dave Barry, I just wrote, like, humorous columns for the school paper and, you know, just kind of did that a little bit, then set it aside. And then, I became what back in the day was known as a war blogger. You know, a little bit after 9/11, everybody started blogging and trying to get involved in the news. And I think I was about, let’s say, I’d be about 23 at the time. And I said, “Well, I’ll write some on politics.” But I also realized, “I’m too young to lecture anybody on politics. I don’t know anything, so, I’ll just write really stupid opinions that will at least be entertaining,” and made that my niche, and first started out as blogging and eventually started writing some columns and things.

As opposed to stupid opinions that aren’t entertaining, and there’s lots of those around.

Yeah, but, well, stupid opinions are the most entertaining. Smart opinions are usually very simple.

Well, I have to ask you about the Babylon Bee, because that’s how I found you. How did . . . are you one of the founders of that or . . . you’re listed as a senior writer. So, how did that all come about?

I’m one of the earlier writers. I’m not a founder. I think they were out maybe about two years because I remember being a fan of them before I got involved. I knew, you know, I already mentioned Ethan Nicolle, and I was a big fan of his. And I ended up just meeting him online, becoming friends with him. And then he went working for them full-time, and he dropped my name with them. And it’s just, I’d been blogging, writing similar-type humor for over a decade, so it just was a real good fit. Because I used to write full columns where I’d have, like, a joke, a funny idea, and I’d have to fill out 600 to a thousand, and really I’d just have one joke, and so that’s all padding. I like the Bee because I just come up with a funny concept and usually only write, like, 200 words or so. And so, it’s usually pretty fun to write for.

My background is in journalism, and when I was working as a newspaper reporter and photographer at the little Weyburn Review—Weyburn has a population of 10,000, so this wasn’t exactly a huge newspaper—and I had a weekly column, and I would sometimes dip into satire. And I found that people would get madder at me for the satire than things that I had written, you know, serious news stories about serious topics. But people were sometimes . . . especially if they took the satire seriously and then found out afterwards that it was satire and they’d missed the joke. Does that . . . ?

Well, yeah, that’s always the problem. My very first paid column, I actually co-wrote it with Jonah Goldberg for USA Today. And there, they were very particular. It said, like, satire right in the title and satire right at the end. And, you know, I know why they do that, but I always feel that puts you off on a bad foot, like, you’re like, “You’re too dumb to get this was a joke if we didn’t tell you right away.” For a while, I wrote, though, for the New York Post, and there, they didn’t label it, but no one seemed to get that mad. I seemed to, you know, I never had, like, these most strident, ardent opinions that really worked people up. I think a few people wrote in some angry letters who didn’t get it was satire, but it didn’t seem to be a big deal. Of course, now, at the Babylon Bee, we keep having all these times where people share it for real, and, of course, we get accused, like we’re trying to do that. We’ve never written one where we’re trying to trick people. It’s just, it so often takes us off guard, like, which ones people thought were real and end up getting shared as, you know, fake news, and that that will get people angry.

And a few times, your satire has turned into almost what actually happens a few weeks later on, too.

Yeah, that’s what I was saying recently, is satire these days is just figuring out what’s going to be real news in about, you know, two days in the future.

And I guess that’s where a Not the Bee came along because those are real news items that read like they could be satire.

Yeah, yeah. It’s . . . and that’s, I think, actually a challenge for satire. If things are already crazy and funny, you can’t really . . . you know, it’s better if something’s really serious and you make fun of it, you know, like, you throw a pie in the face of some stiff, you know, upper-crust guy, throwing a pie in the face of a clown, not as funny. And it’s . . . and with things so crazy, it’s a little bit more challenge for the humor. You have to learn how to, like, work with it instead of against it. It’s . . . as I describe to people, if you, like, a decade or two ago, you pitched, “Hey, Donald Trump is going to be president,” you know, no one would do that as a drama. That’s a comedy. And so, I explain people are living in a comedy premise. And you have to learn to, like, flow with that and be with it and not get all too serious about it, or you’re going to end up like Dean Wormer from Animal House.

I also wanted to ask you about the scriptwriting side. We’re working our way around to the fiction, but I’m touching on everything else that you’ve done. You mentioned being a scriptwriter. How did you get into scriptwriting?

I had an opportunity where I worked with a production company in Austin. It’s what moved me to Texas. They’re called Emergent Order. They’re probably most famous . . . they did, like, a Keynes versus Hayek rap battle explaining economics. And I did with them a series which portrayed government as, like, kind of this bad boyfriend who’s always butting in, and had a lot of fun. That was my first time writing and getting to see it filmed, which is a lot more complicated. And I thought . . . and it kind of ruins TV and movies for you afterwards, because now I’m always thinking practically, like, “Oh, how many extras have they got, where did they film this, what camera angles.” In a way, you can enjoy TV more before you know all the background stuff. And now, I’m actually writing some scripts for, you know, Babylon Bee started doing some animation. They’re really expanding what they’re doing on YouTube. And so, having some fun there.

Well, one reason I ask about scriptwriting is because, as we’ve come around to your fiction, all these other kinds of writing that you have done, have you found them helpful when you started turning your attention to fiction? I think in scriptwriting—and I’ve done plays, and a few video scripts, mostly more plays than anything else—one thing that you quickly learn is that dialogue has to carry a lot of the action in a play. So, do you find, for example, that being a scriptwriter has helped with the dialogue in your fiction?

Well, I think my problem is I love dialogue. I want to start with the dialogue. It’s like, I’ll do the dialogue and then start to get the plot around it. And that’s kind of the wrong way to do things. So, I’ve actually, with scriptwriting, had to learn more discipline to outline and get the plot points and beats. And after I get everything, then I can finally write the dialogue, because that’s my favorite part. And so . . . and you know, there’s the length of it, because a lot of the, you know, I’d say, like, the humor writing, that doesn’t really contribute much to the fiction writing. To me, I love the fiction writing because it’s different when you actually have a plot and characters, and you need to make it all come together. And to me, it’s more like engineering in that it’s a bit of a puzzle, in that, you know, there’s no exact right way to come at it. But you have to work at it and try different things until it finally fits together and works.

Well, let’s get around to the fiction. You sort of talked a little bit about how you decided to start doing it, but before we do anything else, maybe we should get a synopsis, however much you want to say, about the Superego books.

Well, it’s funny. I’m not even sure how I ended up with this character because it’s . . . I like funnier, lighter things, but, of course, the main character of Superego is a psychopath. He’s an intergalactic hitman who just . . . and basically, it’s, to me, I guess it was an exploration of morality by . . . I came up with a character who has absolutely no practical use for it. He doesn’t feel guilt. He doesn’t have to, usually, worry about retribution for anything he does. So, is there any use of morality for a character like that? And that’s where I think, in a way, the story’s exploring.

You’re not sure where he came from?

Yeah, I’m not sure how I ended up with someone with absolutely no . . . like, a psychopath without any feeling of guilt. It just . . . it seemed like an interesting character to work with. I think at the time, I remember it was back, I was watching that show House, and I also liked the idea of just this cranky character who can say whatever he’s thinking because he doesn’t really care about other people.

And then, do you want to give a little outline of the plot?

Well, in the first one, he, let’s see, he ends up having to pretend to be with law enforcement when he’s on a planet doing a job and ends up working with a detective whom he begins to fall in love with. But he, you know, finds out that the job isn’t what it seems. And he ends up sort of a . . . well, I don’t know how much to give away, but it just thinks his basically his whole life starts to collapse around him when he hadn’t really thought much about it. The second one has him . . . now he’s decided to be somebody different and exploring how different can he be considering who he is. In a way, he’s trying to be a hero, even though, again, he doesn’t get the feelings of, like, any good feelings from helping people or anything. And so, we’re seeing how far he can push that.

The other interesting thing I found . . . he has an AI in his head who struck me as, like, Jiminy Cricket, actually, he’s the conscience of the puppet in Pinocchio, and it was a bit like that. So, where did that come from?

I’m not sure where the character first came from. I figure . . . I think it’s just, in a way, logical. He is not a people person, he doesn’t do well with people, but he needs help. I actually have a short story that is kind of a prequel that shows him first activating AI. He’s lonely, but he also doesn’t do well with people. And so, he ended up with an AI. He figured he could deal better with that. And so . . . and then, yeah, it’s like a conscience forum, but in a way, he can understand because, you know, it’s an AI, it has to logically think through, you know, what’s the right thing to do here. And that’s what he’s stuck with doing because he has no feeling of like, you know, this is a good thing, or this is a bad thing.

Well, let’s start at the very beginning of the writing process, then. Once you had your character, what did your planning, and what does your planning/outlining process, look like? Are you a detailed outliner, or do you just sort of start writing and see what happens?

I’m somewhere in between. I once tried . . . I read, like, Stephen King’s On Writing book, where he seems to be, let’s just, like, come up with the characters and let happen what happens. And I tried that with the novel Side Quest, but I ended up . . . to me, I need at least a skeleton of what I think the whole story is going to map out, like, where different plot points are, where it’s going to end up. And I tend to just kind of walk around, play with it in my head, until I think I have a solid structure for the plot and what are the main beats of the story in my head, and then I start to write it out. And then . . . but it usually then, it usually takes a few twists and turns from what I originally planned, because you have to, you know, let the characters do what seems logical for them. Because, of course, the problem, if you map out a plot too much, is you’re trying to make your characters fit into doing what you need them to do, and sometimes that just doesn’t work out.

What you put down on paper before you start writing? Is it fairly sketchy, sort of just to remind you of what you thought about, or do you do something pretty detailed? Like, would it be five pages or ten pages or . . . I talked to one author, Peter V. Brett, who does 150-page outlines. So, he’s the extreme.

I’m definitely on the other end. I have a . . . for the current, I’ve written a third Superego, I have a very simple Excel sheet that just maps out a few different plot points, and only because this one’s a little bit more complicated than the others because I’m juggling a few more storylines.

Do you do anything like character sheets or detailed character sketches, that sort of thing?

No. I’m starting to think I need to do that because part of it also is just all the, you know, different names of planets and . . .

Continuity.

. . . characters . . . and then, you know, it goes back to the first two books, and it’s, sometimes, I’m just writing a note. I was like, “Oh, yeah, I’ve got to go look back up in the second book, what was the name of this planet?” And fill this in later. And it’s . . . my first drafts tend to be completely unreadable, filled with holes, have whole sections that need to be rewritten because I said something else is going to happen, so I need to rewrite the old part. But I like to keep momentum, so I don’t . . . for the first draft, if it’s something I’m stuck on, I’ll just write a note, what I want, you know, and then move on, because I like to move through the first thing and say I finished the first draft, even though it’s unreadable, and then go back and pound it into something I can give to a beta reader.

You mentioned a little bit about your actual writing process taking place largely early in the morning. I would presume you write on a computer, you’re not with a quill pen on parchment, under a tree somewhere.

Yeah, I’ve been a computer word-processor since I was a kid. Of course, first it was on a Tandy, but now I usually write in Google Docs because it’s just easy to access from anywhere. And then, for the more final revisions, I move to a Word document.

I like to say that . . . my first computer that I wrote on was a Commodore 64. There was word processing software called Paperclip, which was pretty good, but it was not what-you-see-is-what-you-get, it was just text scrolling across the page. No line breaks at the end of the text unless you put in a hard return, and it was 499 lines of text, which worked out in manuscript format to about ten pages. And so, for quite a while, all my books had ten-page chapters because that’s where I ran out of space on the word processer, and I just adapted to that. It’s funny how your technology can affect the way that you work.

Yeah. I mean, we’re still dealing with things set by typewriters, because that’s, you know, that’s what we’re imitating.

Yeah. And I also had . . . because publishers would not take dot-matrix printouts, and I certainly didn’t have a laser printer, I got a daisy-wheel printer, which was faster than typing, but I had to manually feed each sheet of paper into it as it typed it. So, I would just sit there and scroll in new paper every time it got to the end of the page. It was . . . I don’t miss that at all.

Yeah, I prefer the all-digital route, and I’m one of those . . . I like my books on a Kindle because I now find a physical book kind of cumbersome.

Well, as I get older, I like the fact it’s bright, and you can make the print bigger if you need to. That’s helped.

Yeah. Yeah.

So, are you a fast writer or a slow writer? How many words would you crank out in a writing session?

I am a slow writer, and that’s by necessity because I have, like, a couple of hours in the morning, and I’m also writing, you know, I write at least one Babylon Bee article per day. And sometimes, I have other writing projects going on; before, I was a co-writing a movie script. And so, I write what I can per day. I, you know, I’m happy if I do over a thousand words. You know, I’d love to write longer, you know, be able to write faster. Right now, I just . . . my goal is to get out a novel a year. But it really does change the novel by writing that slow because I have more time to think out each part and allow some more time for the story to evolve, to think, “Oh, wait, wouldn’t this work instead?” And, you know, sometimes that involves having to go back and change huge sections, but I think it makes the story stronger overall to write it that slowly.

Now, you’re writing far-future science fiction and interstellar travel, that sort of thing. And you’re engineer. How hard do you work to make it as scientifically plausible as possible?

Yeah, that seems to be, I say, a contradiction. I am a . . . future tech is just magic, and I don’t really care how it works unless that would help with the plot. You know, you add limitations as you need to. I could say, one of them was, “OK, I have it. They use some sort of tech to jump.” And then, I realize in the second book I need to add some limitation where it takes a long time to charge up so you can’t just jump away quickly because I just need that for the plot. And so, I add things like that as I go, because to me, I guess, it’s . . . the characters are more what I’m interested in than the technology. And the thing is, I really like hard science fiction where they obviously put a lot of thought into it, but I guess that’s just not my focus in my own stories.

Well, and I always feel that as soon as you stipulate faster-than-light travel and maybe artificial gravity on your starships, you’re pretty much playing with technology that you can do whatever you want.

It’s, yeah, there’s stuff you just handwave because it would take so much time out of the story. I have some, you know, they have a universal translator. It’s one of those things where maybe eventually I’ll go into where that works if it’s plot-relevant, it would be interesting if that fails at some point. But, yeah, a lot of it is just, you know, some of it’s just handwaves to do what you need to do in the story. But, you know, when I establish something, then you have to logically follow, “OK, how does this affect things?” If you can jump quickly anywhere, how does that affect laws between, like, planets? It’s very easy to just escape and go somewhere else in the universe and never be found again. And so, you know, to me, those implications are what’s interesting.

It’s like working out the rules for a magic system. Have you ever had any desire to write on the fantasy side of things? Or have you?

Yes, I’ve . . . it’s like, one of my oldest stories that’s been in my head is a fantasy epic. I think it goes back to, like, I played Dungeons & Dragons a little bit as a kid. And I’ve always had this story, developing a long time, it’s . . . eventually I hope to get to that. It’s just, you know, I have my writing schedule. I try . . . right now, I focus on getting one novel done at a time, I don’t try to write multiple at the same time, so . . . but, yeah, I don’t think I’d be doing a very strict magic system. But, you know, again, it has to follow at least some logic, so people understand, you know, limitations and things like that, which you need for a plot to work.

Yeah. Otherwise, it’s just . . . you can’t tell a story without limiting what your characters could do. It just doesn’t work. So, you mentioned a little bit about your revision, that you get to the end, you have a first draft that’s full of holes and things you have to go back and fix. So, tell me about your revision process. What happens when you get to the end of the first draft?

Well, first, I think . . . I’m getting close to that now for the third one and . . . what I guess the first thing I do is, some of the biggest holes are actually names for made-up things because I hate coming up with made-up names. I never came up with a good process for that. I think I use street names for some things in the first Superego.

I have one where my character names are . . . I was doing a production of—I’m an actor as well—I was doing a production of Beauty and the Beast up in Saskatoon while I was writing this book, and as a result, about six characters are named after actors who are in that production.

Yeah, to me . . . I had some street names nearby that sounded at least a bit like, you know, planet names or something. So, I used those. And then I’ve used a few, like, online random-name generators and things like that, especially. I use that all the time with the Babylon Bee if I just need some random name, you know, but they’re good for human names. You come up with alien names, and it always gets like, you know, you want at least a certain style to each certain alien and things like that. And it’s not something, again, that I care about. It’s one of those things like, you know, you have to do. So, part of it’s filling in the names. And then, I tend to . . . my habit is to write in brackets notes for myself. And so, to get from my first draft to something readable, which at first will go to my alpha reader, which is always my wife, whose job it is to make sure I don’t embarrass myself too much, I just can search for brackets. And once I’m getting all the brackets out of the story, then it’s done, and it’s readable now. And so, what I do is, I’ll go back, and I’ll start to fill in those sections and rewrite the sections that now have to be changed because I decided to go somewhere else later on, and I’ll fill in all the names, and then once I search the document and all the brackets are gone, now I have something someone else can read.

Just on the writing side itself, do you, like, go back and do all the tightening up the language and making scenes more vivid and all that sort of stuff at this stage? Or do you get it right the first time?

Some of it . . . my biggest weakness, I think, is describing things. It’s one of those things I never felt very good at. And again, it’s like, I want to get on to the action. I want to get on to the character drama. And so, I just want to describe things enough so you understand what’s going on, what you can see. But sometimes, you know, you need to add a bit more, really, to draw people into it. And so, that’s one of those things I really have to force myself to concentrate more on. So, yeah, I’ll try to increase the descriptions when I come back to it and also just notice the flow. And then, one of the biggest things I worry about is repetition, where I, you know, because I write over such a long time, I forget, “Oh, I already had the character say something similar in the previous section.” So, I do need to read through a few times and make sure things don’t get repeated and just sort of look at the flow of it, which is . . . it’s hard to tell because you’re . . . especially for something you’ve read over so many times.

You mentioned your wife is your alpha reader, but you also mentioned that you have beta readers.

Mm-hmm.

Where do you find them, and what do they do for you?

I just go to . . . I’ve been lucky to at least have fans been lucky at least have fans, at least initially for my blog and now for my fiction writing. And I keep an email list, and I usually just go to them and see who’s interested, and I’ll send out copies to get feedback. And, you know, and . . . of course, that’s one of those things is, how do you react to the feedback? And usually, you know, if a number of different people mention the same thing, then, you know, that’s something you need to really pay attention to.

How many beta readers do you have?

At least . . . just probably a little over a dozen. It’s just, you know, it’s whoever’s interested. Last time, for the Superego sequel, I had quite a number because a number of people were fans of the first one. I probably did more than a dozen, but we’ll see. I don’t know what’s, like, a good number there, but I feel like as long as I get some quality feedback, it’ll help me know what I need to fix. I didn’t do as many big revisions on Superego: Fathom. I think that worked out pretty well by the time I got it to beta readers.

Do they tend to give you consistent feedback, or is it all over the map?

Sometimes over the map, but, you know, sometimes you really have to read between the lines and see if people run into the same problems. I got some pretty bad feedback on . . . Superego: Fathom, I think that worked out really well, I was really happy with that one. Hellbender, I think, had a bit more problems. That was more of a straight comedy one. And I went back and had to, I think, make the characters a little bit nicer. To me, I don’t like stories where people don’t like the main characters. I know you have a lot of that in fiction these days, especially TV shows. And so, I try to make them a bit more likable because I feel you get into the story more if you’re at least rooting for people.

Well, your main character’s likable; he just happens to be a psychopath.

Yeah, a lot of people, that’s the problem, and that’s . . . it’s not going to be for everyone. Some people are just not going to like Rico. But a lot of people seem to respond well to him. Because you have to sympathize with him, or the story’s just not going to work. And even though he’s kind of out there, I need the reader to see something of themselves in there. I think in a way, they’re situations they can relate to, his awkwardness around other people. And yeah, if you’re not . . . if you just hate the guy and you’re not rooting for him, the story doesn’t work.

So, once you have taken into account all of those revisions, I presume you get an editor involved at some point . . .or do you?

Yes, I get editors . . . before, my wife has actually worked on editing Superego, sometimes I’ve had other people just, you know, hired out editors, but I am not technically . . . let’s say I’m very bad at proofing myself. I would never trust myself to edit one of these things. And I always tend to be really lousy with passive voice, and I’m bad at spotting it in my own writing, so I need a lot of fixes there.

So that sounds more like copyediting. Do you get a developmental editor of any sort involved, or is that sort of taken care of by the beta readers?

Yeah, a bit with the beta readers, though, you know, I do like editors who actually look at, like, story-wise, does this work, and did you establish just enough. So not, yeah, not just the writing, but actually making things fit together, spotted where I inconsistently used a planet name, that sort of thing.

Yeah. It’s always helpful to have somebody else look at your stuff, that’s for sure. And I do some editing, and I’m looking at other people’s stuff, and I sometimes find by editing other people, I find, I realize stuff that I’m doing in mine that I shouldn’t be doing. So, it’s kind of educational reading other people’s stuff as well as working on your own.

Yeah, I think it’d probably be useful if I tried editing others to get better at it myself. But it’s is so hard for me to see my own writing. To me, that’s . . . I really like when I get to the Audible version, because to me, that’s the first time I really get to detach enough that I can really hear my story for the first time all and complete because it’s there now, someone else is interpreting it, acting it out a bit. But just going back and reading your own writing and trying to see it as other people would see it is so hard.

I was interested in the audiobook and the fact that you listen to them because I often ask authors if they listen to the audiobooks of their books and, more often than not, they say they don’t. They might listen to a little bit, but they don’t listen to the whole thing. It sounds like you like to listen to the whole thing. And do you find that helpful for the next book after you’ve heard it with those sort of fresh ears?

Yes, I think that, to me, was very helpful with the first Superego. That was actually a surprise, I didn’t know the publisher was going to do an audiobook. And so, that was my first experience. To me, it was very surreal when I got sent a list of all my made-up science-fiction names and was asked how to pronounce them. At least, I did have a pronunciation in my head for each one. And then listening to it, you know, like I said, I really got to feel it for the first time. I got to see what parts where I was not paying attention and what parts really drew me in. I know at one point I was like, you know, as I’d listen to, like, in my car on a commute, you know, I’d get home ,and I’d stay in the car for a while listening because, “Oh, this is interesting what happens,” because, you know, this is all, right now, a couple of years since I wrote it, so at least I’d forgotten some of it. And that helped me determine, I think . . . with the first one, a lot of people . . . like, the beginning part of Superego, I felt it takes a little time to get the momentum. And to me, there’s one chapter where afterwards it has this momentum that just really grips you until the very end. And so, that influenced the sequel because I wanted to start with that at the beginning and try to keep up that pace for the entire novel.

Now, the publisher, NTM Publishing, I have not heard of them, so . . .

Well, that one . . . originally I was with Liberty Island . . .

I have heard of that one.

NTM is my own imprint. Now I’ve decided to go the self-publishing route. To me, it’s just less stressful, because I’m only having to worry about . . . the only one I’m answering to about sales is myself. And also, that’s part of the reason I do want to listen to the audiobooks because I’m paying for those and I want to make sure, you know, there’s no errors and things in them before they get released, because I think . . . for quality ones, you know, it’s not cheap.

The only audiobooks that I . . . I do both, I’m published by DAW Books in New York, but I’m also published by myself through Shadowpaw Press, which is named after our cat. And there are some books that I had the audio rights to that were published by somebody else. And so, I did that where I found . . . I’ve narrated some of my own, but in this case, the main character is a teenage girl, and I don’t really have the voice for that . . . I don’t have much voice today, I’m quite hoarse . . . so, I got a narrator to do that. And that was, I think, the only time I’ve listened to my books all the way through. But I really liked that narrator, though, and I really enjoyed my own books because she found things in it that I had not, you know, they got tweaked a little differently. So, I do . . . but you have to have a good narrator. Have you had the same narrator for both of the Superego books?

Yes, I went back because . . . I wasn’t the one who hired him for the first one. But I did, I went back and approached him for the sequel, and so, I got the same narrator, and, you know, if you want to get, you know, it’s not cheap to pay for these things, especially if you’re paying someone, like, who’s at union rates. But I think, yeah, it’s very worthwhile to get somebody who knows what they’re doing and also, like I said, knows how to really perform and pull something out of the text. Sometimes, they find things maybe you didn’t even see in there. And like I said, it’s interesting because now, like, the story’s not completely just yours anymore. When someone else reads it like that, they are adding their own take to it.

Well, and I like to think, and to say, that even though it’s very obvious in an audiobook that somebody else is getting something a little different out of it. That, of course, is happening with every one of your readers because although we sit alone and we write our stories, the story is actually re-created in the head of each reader as they read it. And they’re all going to actually have a different a slightly different take on your story than what’s going on in your head when you write it. And I think . . . when I think about that, I’m always kind of fascinated by that. It’s a very . . . it feels like a solo activity, but it’s really a collaborative activity.

Yeah. And I wish I could experience how they read it in their head because, to me, that’s the sort of feedback I would like to. You know, I work on, you know, Babylon Bee, or work on Twitter. I have these things where, you know, I write them and then sometimes, you know, it’s usually within seconds I get feedback or, you know, within a day I get feedback and see how people are reacting. The novel writing is a bit lonelier. It takes sometimes years to get it out there, and you don’t get, like, the line-by-line feedback you’d quite like to. But, you know, I’d really like to . . . I mean, to me, I would love to get in people’s heads and see exactly how they read each section and see that. Like I said, you get a little bit of that with the audiobook.

Might be a science fiction story there with an author who develops the way to see inside readers’ heads as they’re reading his story. It sounds like a good idea. So, what has the reaction been for your fiction? Has it has been well-received?

Yeah, I feel it’s been really well received. Superego’s been quite popular. That’s definitely my most-read book so far. Part of that was also actually because of the audiobook. It got featured once . . . was made Audible’s deal of the day. So, I got to experience being the number-one audiobook for a day. And some people, they really reacted to the main character, really liked it, and then I feel the sequel’s been a big success, people who like the first one seems to love the second one. I’m hoping . . . most people consider that one even better than the first one, and I got a lot of feedback to that. And now I’m just scared with the third one because I’m trying something a bit different. And it’s going to . . .the pacing is going to be a bit different. But, you know, you have to try new things with each story. I wish I could have, like, a rut where I’m making, like, the same character and same story beats each time. But I don’t think I can do that. I’m more . . . I want an epic scope, so it’s all, you know, all these books are going to fit together in one big story. It does, it will have a conclusion. They’ll be, like, we have two books out, and there’ll be two more. And that will end the story.

So, it’ll be four all together. A quadrology.

Yeah. I mean, originally, I wrote the book, the first book, without necessarily thinking there’d be a sequel. It was the idea that it had an ambiguous ending, where you weren’t sure if Rico died or not, but no one thought he did, and everyone was asking where the sequel was. And since then, I’ve kind of thought out the rest of this story and it’s just going to fit, it’s going to be, you know, three more books after the first one, well, I have to out now, working on the third one, then I’ll have a fourth coming.

Well, we’re getting into the last little bit of this, so I’ll go to my big philosophical questions—and I’m totally going to put reverb on that one of these days, “big philosophical questions.” Three questions, I guess. Why do you write? Why do you think people, in general, write? And why science fiction in particular? So, we’ll start with, why do you write? Why do you do all this?

It’s . . . I have these ideas. I want to share them. And writing is the easiest way, I think, to do that. It’s something accessible to everyone. I say it’s . . . and this is something I determined a while ago. It’s just, I’m always going to come up with stories in my head, ever since I was a little kid, and they’re always going to . . . they’re almost like demons I have to exorcise. The only way to do that is to write the story down because once I’ve written the story, I don’t think about it anymore. I don’t keep thinking, “Oh, we could do this, do this.” It’s done. It’s out there. And so, the only way to get these stories to stop bothering me is to write them down. And so, it’s one of those things where it’s like, I have to write, you know, regardless of what success I have there, it’s something I need to do.

And why do you think humans, in general, tell stories through writing and through other media? Where does that come from?

That isn’t . . . yeah, that is not a philosophical question I think I’ve thought long on. But, you know, it’s yeah, we’re very compelled to communicate these ideas through stories. You know, it’s funny because, you know, I’m an engineer, I’ll, you know, I don’t always use metaphorical language. I’ll tell you very succinctly exactly what I’m thinking and what I want to get done. But stories, I think they allow you to tackle much more complex subjects, things you can’t just write out and have, you know, a simple answer to explain. You have to follow characters. You have to see stories. You have to see how they react and just kind of develop an understanding, even if you can’t verbalize all of it.

You’ve done some work with virtual reality and, in a way, fiction is a form of virtual reality. If it’s done well, you feel immersed into a world that’s not real, and yet it feels real to you. So, it’s sort of the same impulse, I think, to experience other lives and other ways of seeing things and have experiences, virtual experiences, that aren’t real experiences that you probably wouldn’t want to have. You wouldn’t actually want to experience what Rico goes through. But it’s exciting to experience it virtually.

Yeah. I mean, that’s a good analogy. You’re trying to draw people into . . . I mean, if you can do it well, people really immerse, you forget about things for a while. And, you know, that’s my main goal of a story, is to entertain and give people, you know, a little bit of a vacation from things. It’s funny; things are so crazy, even as bad as things get, like, you know, in Superego: Fathom you have this entity trying to take over the universe, and no one knows about it, and it’s a crazy world, but in a way, it’s a nice little . . . jumping in there is still a vacation from how crazy things have gotten in the real world. So, I think people could appreciate that. And I like, you know, I write a lot in satire and politics and things like that. But it’s I like, I mainly like to stay away from that in my fiction. I think I want to tackle bigger subjects than, like, you know, temporary issues, and give people a break from all those real-world things.

And is that why science fiction/fantasy? Because it’s a way that you can talk about bigger issues, but sort of disconnected from the here and now?

Yeah, in a way, I think of myself as a fantasy writer, even when doing science fiction, because it allows you, you know, you have less of a box you’re stuck in. You can do a lot more things. You can do whatever you want. And some of it’s laziness, too, because I don’t have to research as much. I can just make things up. And that’s part of why I write, like, political satire and things like that. I don’t have to do all this research for these well-thought-out opinions, I just make things up.

Well, and you sort of mentioned that you’re working on the third book, but is there anything else that you have in the works that are coming up soon?

Yeah, well, I’m working on the third book . . .

And when will that third book be?

I don’t . . . I’m hoping, sometime early next year. We’ll see how that works out. You know, there’s a number of things to get, you know, you get it done, you get it edited, you get a cover. But then I think I’m going to take a little break to do a sequel to Hellbender. Superego’s a bit dark. Hellbender is straight comedy, and I think I’d like a little break into that for a little while before I write the fourth and final . . . probably final . . . And then I, you know, my other writing right now has been doing lots of stuff with the Babylon Bee, and I’m hoping to do more animation projects with them too.

We should probably mention just a little bit more about Hellbender. You’ve mentioned it a couple of times but haven’t really said what it is. So, here’s your opportunity.

Okay, that is a science fiction comedy about . . . like, you know, it’s sort of a post-apocalyptic world, but for orphans who are . . . it’s kind of them against the world, and it’s always been a hard one to describe, plot-wise. But that’s one where . . . I think that was the most me novel, where I’m just having fun and having lots of jokes in it. But I still felt the need to have a solid plot that draws you in, and you don’t know where it’s going to go. And then, I also have one other novel, Sidequest, which to me is a stand-alone, and a lot of people . . .that also got a very big reaction. It’s probably my most Christian novel, even though God isn’t mentioned in it at all. It’s sort of a metaphorical one, but that’s, I’d say, between a straight comedy and Superego, and I really enjoyed that one, though I don’t know if I’ll go back to it. A lot of people . . . I got mixed things on the ending. I thought I stuck the landing on the ending, and a lot of people didn’t like it.

You can’t please everyone. You may have noticed that. And where can people find you online?

Well, I’m very active on Twitter, quite a following there. Just look for Frank J. Fleming on Twitter. My handle is based on my blog name, it’s @IMAO_, because IMAO was already taken. And then, you can catch my writing on the Babylon Bee, go to BabylonBee.com. And also, you know, I have a website where you can see some short stories and also just shows all my novels, and that’s FrankJFleming.com.

All right. Well, I guess this brings us to the end, so thanks so much for being on The Worldshapers. I enjoyed the chat. I hope you did, too.

Thanks. Yeah, it was great.