Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

An hour-long chat with Jane Yolen, the much-honored, multiple-award-winning author of some 400 books for children and adults.

Website

www.janeyolen.com

Twitter

@janeyolen

Instagram

@jyolen

Facebook

@jane.yolen

Jane Yolen is the author of some 400 books for children and adults. Her stories and poems have won the Caldecott Medal, two Nebula Awards, two Christopher Medals, three World Fantasy Awards, three Mythopoeic Fantasy Awards, two Golden Kite Awards, the Jewish Book Award and the Massachusetts Center for the Book award. She has also won the World Fantasy Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award, the Science Fiction Writers of America’s Grand Master Award, and the Science Fiction Poetry Associations Grand Master Award (the three together she calls the Trifecta). Plus she has won both the Association of Jewish Libraries Award and the Catholic Libraries Medal. Also the DuGrummond Medal and the Kerlan Award, and the Ann Izard story-telling award at least three times. Six colleges and universities have given her honorary doctorates for her body of work, so–she jokingly says–you could call her Dr. Dr. Dr. Dr. Dr. Dr. Yolen, though she can’t set a leg. She lives in Massachusetts much of the year and in Scotland the rest of the year.

The (Lightly Edited) Transcript

Jane, welcome to The Worldshapers.

Well, thank you very much. It’s always interesting to hear your life done in in short form. And even when I write it myself, I’m always a little behind the times.

I always like to see if I can find a connection. We have not met in person, but back when you had Jane Yolen books, you did reject me once. So, there’s that. Actually, I was a very nice rejection because you said that there was nothing wrong with the book—it was a fantasy called The Dark Unicorn—and that a larger house might very well be able to take it on, it just didn’t suit your house, which, you know, was a lot better than just getting the form rejection backroad. So, I appreciated it at the time. And the book did eventually find a not very good home, but I’m going to be revising it and bringing out it out again with my own little publishing company before too long. And it did get nominated for an award so well that that was it was very nice to get that sort of personal response from you back then.

I don’t want to make you nervous or anything, but I still get rejections. And I love my rejections because, one, they mean somebody read it, then I can move on. But the other thing is the rejections recently say things like this is lyrical, lovely writing. I love the characters. It’s not for us.

Well, I’ve had my share of rejections now after all the years I’ve been writing. And you have 400 books. I only have 60 or so, so I’m well behind you. But still. So ,we’re going to start with, what I usually say is, taking you back into the mists of time just to find out about your, you know, you’re growing up and how you got interested in and writing. Most of us started as readers and then became writers. And how did that all play out for you? So, tell me about yourself, Jane.

Well, there’s a lot to tell because I’m 82 years old. We might be on this for seventy-two hours. I grew up in a family, a Jewish family in New York, and there were books everywhere. My parents made no distinction between what books we could and we couldn’t read. If we were interested in it and we could get through it, we could read it, which meant that I was reading stuff so far over my head when I was four years old. But I loved the sound of the language and I think that stayed with me all of my life.

My father was a journalist who had become, by the time I came along, had become a head of the Overseas Press Club. But he then left journalism itself and became first, a promotion person and then became a vice president at Hill and Knowlton, which was public relations. And he was the one who was involved with getting people into newspapers, magazines, and books. So, there were always books there. And he actually wrote, I am going to use quotes around the term “wrote,” because he got other people to write for him, six or seven books under his name. He never wrote any of them. I wrote the first one that was actually my first book, but I don’t count it because my name isn’t on it. And my brother became a journalist. My mother wrote short stories, but only sold one in her life. But she also made and sold crossword puzzles and double acrostics and all their friends were known and very well-known writers. They ranged from the very known ones like Hemingway and James Thurber to people you and I still don’t know today. But it meant that as I was growing up, I thought that all grown-ups were writers, I knew they were teachers, like, librarians, butchers, bakers, candlestick makers, the cop on the beat. I mean, I lived in New York City, I saw all of this. I thought that was their day job. And at night, they all went home to write. So in my little pea brain at that moment came the idea that whatever I did during the day, I would be a writer because I’d go home at night and write and that . . . it’s sometimes metaphor, but it’s absolutely true.

It’s interesting because I talk to so many writers who say, you know, when I was growing up, I never knew a writer. I didn’t know people could be writers. And then they found out they could be a writer. And you’re just quite the opposite.

Absolutely. And if you ask that, if you talk to my brother who lives in Brazil, who is a newspaper man for all of his life, he’d say pretty much the same thing.

So when did you . . . I assume you started writing as a child?

I wrote as a child. I mean, I, you know, I was the writer in my elementary school, although I wrote class plays that we all played in, I wrote poems, I wrote little lyrics to songs. And the same thing happened once I got into high school. I was the one who was known as the writer. And in college it was the same. I wrote a lot of songs, a lot of short stories, but mostly poetry.

Were there books that particularly influenced you during those early years?

Well, I was a huge King Arthur fan, so I read everything anybody ever wrote about King Arthur. So, yes, along the way I’ve written three or four King Arthur books myself, but I love folk and fairy tales. And Hans Christian Andersen. Oscar Wilde absolutely fascinated me. And it was poetry that stuck with me all through my life, I’m still writing poetry to this to this day.

What was it that drew you to poetry?

I think because I was very musical to begin with, so I started with lyrics. And, you know, we’re talking George Gershwin here, right? But then as I grew up, people like Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen were writing the kind of music I like, but the kind of also lyrics that I like that were really poems set to music. That kind of, you know, calcified for me.

It’s interesting. I have committed poetry, I don’t know if it’s good poetry or not, but they are very different writing disciplines, writing, writing prose and in poetry. Do you find that writing the poetry informs your prose, the way that you write prose?

I write very lyrical prose, but I tell you, I know when a picture book or a novel or short story of mine is good, I don’t know for the most part if a poem is good or good enough, I’m always surprised when people take my poems for journals, magazines, anthologies. half the time. It’s not the poems I would have taken. I’ll them say I send them seven, they take two or three. Those are not the three I would have taken, so I’m not sure why. I don’t know which one of my poems are the best, when I can tell right away if a book works or a story works.

Once you were . . . well, your first book was published when you were about . . . the first official one was published when you were 22. Is that right?

Yes.

So, you were still in university or just out of university?

I was out three years, I graduated in 1960, but I had poetry published all the way through and newspaper stuff and magazine articles published. But my first book, I sold it on my twenty-second birthday. After I sold it, I ran two blocks to the overseas press club where my father was holding court at lunchtime and I said, “Daddy, Daddy, I sold my first book.” And he looked at me and then he looked at all the guys, there weren’t any women, I think, in the Press Club at that time, and he said, “Fellows, drinks are on the house. And a coke for my little girl!”

You then started doing a lot of editorial work in the ’60s, did you not?

Well, I first worked for Knox Berger before he became an agent. He was an editor at one of the paperback reprint publishers and I worked for him for about a year, and then when I sold my first book, and it was a children’s book, I thought maybe I’d better learn more about children’s books. So, I did two things. I took a course in writing for children at the New School, but at the same time I went to a head-hunter and said, “I don’t care who it is, but I want you to find me a job in children’s book publishing in New York City,” because I was living in New York City at that point, and they found me a job with a packager who did children’s books, which was interesting, because then I got to write a lot of stuff within the books that they were doing. My name never got on them, but I got to do that. So, there were a couple of problems in crossword puzzles and fiddly bits in books that I mean, they’re long gone. And this was 1961 to ’62 that I wrote that, that we’ll never know, except me and probably not even me anymore now, that I had done.

It’s a bit like the backup singers on some recordings, like I think of The Jersey Boys where they’re doing backup vocals for four other singers that nobody remembers anymore. But meanwhile, it’s the Four Seasons singing the backup songs back there.

So that’s how we got started. And then one of my fellow editors at the packager was an older woman and she was a friend of mine. And we had to show the packager anything we wrote first because they had first dibs on it. But if the editor rejected it, it was OK and we could take it elsewhere. And her name was Frances Kane. We all called her queen. And she said to me one time, I showed her a manuscript called The Witch Who Wasn’t, and she said, “I’m going to tell you a secret.” She said, “I like this very much, but I don’t want to publish it here. I’m about to take a job as head of MacMillan’s Children’s Publishing. Will you bring it to me there?” I said, “You got it.” Almost maybe my second or third book that was published. And Kate and I remained friends until her death, which was rather too, too soon. But she was very important in my early writing days.

You mentioned that you had taken a course in writing children’s literature at The New School, and I always ask authors who have taken formal writing courses how helpful they were to their career, because I get a variety of answers to that question.

Well, one of the picture books that I tried there, I thought, “Oh, well, there you go.” Things are so different now that the kind of book that I learned about and that I wrote then I would not be able to write and sell now, but I learned to be aware of how these things change. And that’s important. I think one of the reasons I’ve been so successful for so many years, whereas other people have sort of dropped by the wayside, who had started about the same time as I did, is that I’m very flexible and I’m able to do any number of things. And if the picture book world changes, I change with it. If the novel world changes, I change with it. If I can’t get a big publisher to publish something, I get a wonderful small publisher like Tachyon to publish a book of mine. So, I’m infinitely flexible and I love meeting new editors and talking ideas with them, because having been an editor, I was an editor for fifteen years, having been an editor, I know how to talk to editors. I know they’re the friends, not the enemies. Nobody buys a book to make it bad.

Yeah, there are authors, especially new authors, who are kind of scared of editors and think somehow they’re going to take their deathless prose and ruin it somehow, and that’s just not the experience you have with a professional editor. They want a good book, too. So, your experience as an editor. You’re writing and editing at the same time, how do those two things work together? Do you find that by looking at other people’s work, it makes your own work stronger? You’re able to see how other people are dealing with, you know, the same . . . we all encounter the same problems in our writing that we have to solve. You know, characterization and all that stuff. Did you find that being an editor helped you as a writer?

That’s exactly it. But that’s the second thing I learned. The first thing I learned, looking at people’s writing was, “Gee, I’m a good writer,” because a lot of bad stuff comes over the desk. Anyone who is an editor will tell you that. Eighty-five to ninety percent of the stuff that they see is so amateurish, there’s nothing they can do about it. It’s the other ten to fifteen percent that there are possibilities. And more than half of those are not the kind of book that they’re looking for. When I was an editor and editing fantasy and science fiction for middle grade and young adults, I would get coming over my desk nonfiction books, cookbooks, mystery novels, picture books, none of which was of interest to me. But I still had to send a letter back with it. So, the first thing that I say to anyone who’s a writer is look at where you’re sending it, make sure it’s the sort of thing they’re looking for. If you don’t know what they’re looking for, find out. You can ask other authors. You can join groups like the Science Fiction Writers of America or the Society of Children’s Book Writers and find out information. The more you have information about what a particular editor or a particular publisher is looking for, the easier you’re going to make your life.

I suspect the problem of inappropriate material flooding editors’ offices is even worse now with email being a way to submit. It’s just become much easier for those places that take email submissions. The volume must be enormous.

It’s not that, it’s to say we’re open to anyone. You should see who anyone is. They are people who have never finished something, they’ve started it but never finished it. They’ve written a book that’s just like their favorite book, or they’ve taken characters from their favorite book and used them, which is a no-no, unless the author is long dead or has given them permission. So, there are those sorts of things that you get over and over and over again

You’ve won a lot of awards. How did that all ramp up? I mean, you start out like anybody else. You’re selling a few books and then you’ve built and built. So, were you really gratified by the response to your writing over the years?

Well, of course, I’m gratified. Some of the awards that I’ve won, I go to some of the awards that I that I’ve won, I go, “Oh, my God, I’m so honored.” Some of them I’ve said, “I think they missed the mark on this one.” And some of them I say, “Thank you,” and put the thing up in the attic, because honestly, there are more awards out there than there are writers. And they happen year after year after year after year. The ones that I am especially proud of, those are ones that I keep where people can see them. But at this point, I must have, you know, like two or three hundred awards, certificates, that sort of thing. And occasionally they spell my name wrong on it. Occasionally it’s for a book that I think of my work is minor, but the ones that are really special to me, those are the ones that I take out and look at now.

Which one set fire to your coat?

Well, it was this Skylark Award given by the Boston Science Fiction Convention. Not for any particular work, it’s for somebody who has been doing good work and within the community, the science fiction community. And I always volunteered for things at Boskone, which is the science fiction convention. So ,they gave that to me and I took it home, as I did with any award I would get or any certificate. It would sit on my kitchen table for about a week, and then it would sort of slowly move upstairs to the attic. Now, the attic is not just an attic, it is where I store awards, where I have all my extra copies of foreign editions, where I have all my files. So, it’s a library. My entire folklore library is up there, too. So, it’s a little bit like a library/boasting place. But this award, the Skylark award, was sitting there . . . it had been a rather rainy, dark New England winter. And it was sitting in front of the kitchen window, which is a large, a huge, large window. And it was a wooden plinth with a . . . not a microscope, what is it called?

Magnifying glass?

Right, a magnifying glass up top, because it was named after the Lensman series, right? And my husband and I were coming down the stairs to go actually to Smith College where I was winning a Smith Medal, I was a Smith graduate, and I said, “I smell something funny.” We ran into the to the kitchen and my good coat was smoking because it was a beautiful blue-sky day with the sun coming in from the east, pouring in through the windows. If we had gone later, the house might have gone up. So, I called up my friend Bruce Coville, who had been the one to hand me the award, and I told him what happened. And I said, “Bruce, I’m going to have to put this award where the sun don’t shine.” On the other end—Bruce is a huge laugher—dead silence. And I did what I did to say that and I hung up. So, he told the committee what had happened. The committee said that when they gave the next one would I come and say that as a warning. And so that’s become something that every year at Boskone, when they’re giving out the award, I have to run up and say, “Stop, stop, stop! Before you take that award, I need to give you this warning.” And so it’s, you know, it’s fandom at its best.

The Canadian Science Fiction and Fantasy world, the Aurora Award, the current one is just a plexiglass Aurora, but the original one was this piece made out of a laser-cut metal that you could disassemble and put into your suitcase if you were flying after winning one of them. And apparently the trick with that one was, because of all these sharp edges, you had to . . . people discovered that if they didn’t wrap it very carefully in their suitcase, it shredded their clothes. I have one, but I didn’t have that problem.

And I love that story. I never heard that one.

The other thing about it is, it’s very pointy metal in a base. And when I won mine, it was in Montreal, and I discovered that if you pointed it forward people decided to give you more room on the elevator because nobody wanted to get close to it.

All the fandom.

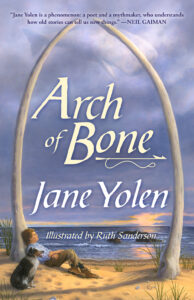

Yeah. So, we’re going to talk about your your upcoming book, Arch of Bone, and we’re going to use that as an example of your general overall writing process, so you can talk about any books you want during this process. But then, you’ve written also for adults and middle grade and young adults. And I want to get your thoughts on the differences among those three. But maybe, first of all, just tell us a little bit about Arch of Bone.

Well, there are stories that are in your heart, and wherever they started, they were in your heart and you want to tell them if you’re a writer. And this was one I carried for a long time. It takes place in 1964 in Nantucket. And it’s really tagging onto the end of one of my all-ime favorite novels, which is Moby Dick. And I was . . . I am in New York City, a Jewish kid loving Moby Dick from the first time I read it, and I would read it as I grew up every ten years because it’s a big book, it takes a long time to read. And any time I was talking to an editor, it was going to be historical, but it was going to have fantastical elements in it. Any time I talked to an editor, they looked at me shellshocked, like, “That doesn’t sound like something I want to do.” So I put it aside and I put it aside and I put it aside for years. And then I started publishing with Tachyon and Tachyon said, “We’re starting a middle-grade young-adult line now and we’d love it if you would have something for us to see.” And I talked to them about this book because it’s a book that starts out a new way. I knew how it was starting out and I knew where it was going.

But there was a major problem. And I’ll tell you that in a minute. I knew it started out with a young boy, a thirteen, fourteen-year-old boy whose mother has been sick with whatever for the whole winter. His father is on a whaling ship, so he’s away. So, the boy is kind of man of the house. His father’s been gone for about a year or so. And it’s early spring. There’s a knock on the door and he opens the door and there’s this man he’s never seen before. And, you know, normally you would know your neighbors in Nantucket. And he says, “Who were you?” And the man says, “Call me Ishmael.” It’s Ishmael coming to tell Starbuck’s wife and son that Starbuck, who was the first mate in Moby Dick, that everybody died except for himself. And so, that’s how I knew it was going to start, and I also knew that the boy being upset about the man staying at their house and thinking that his mother has gone through widowhood, you know, in the day, and now she’s looking at a new man, which is not true. He takes off on his own little cat boat with his dog and into the teeth of a nor’easter. And that’s all I knew.

A great beginning!

He was going to break up on an island. So, it’s going to be Moby Dick meets Robinson Crusoe with some miraculous dreams or oracular dreams. That’s all I knew. But the thing that stopped me over and over again just going ahead and writing it and then trying to peddle it was that you needed a good knowledge of sailing. I had not a good knowledge of . . . I mean, I lived in Massachusetts, but I lived in western Massachusetts. I could go and I could have somebody sail me around to some of the places, but I didn’t have the deep knowledge of it. Fast forward almost sixty years, and I’m working with Tachyon and they ask for it and I’m thinking about it and thinking, you know, I’m in my 80s. If I don’t write this book, it’s never going to get written. But I still am worried about this. And my husband had died 14 years earlier, so I’ve been a widow all that time. And I re-meet a guy that I had dated in college, and we fell in love, we’re married. We’re living together. We have, you know, children and grandchildren. He is a sailor, had his own boat. He would sail, he and his wife, he and his kids, they would sail on this boat all around the Nantucket area because he lives in Mystic, Connecticut. And I said, “Would you read this book?” Well, he’d been a teacher all his life, and one of his favorite books he loved to teach was, guess what, Moby Dick. It was, you know, the right time. And he read it, he showed me charts of the waters, he told me when I had a boat thing wrong, you know, “They don’t say that, they call it this.” He read it very thoroughly for me. And I couldn’t have done it, or I wouldn’t have done it, without him. So, sometimes a book has to sit, sometimes a book has to mature, and sometimes the author has to mature, and sometimes luck has to come into it.

So what did you . . . the idea obviously had been floating around for a very long time, but when you were finally able to do something with it, once you settled down to write, and your other books as well, what does your sort of planning outlining process look like? And I presume it might be different for an adult book, a YA book, and certainly for a picture book. But what does that look like for you?

You think I outlined, do you?

Oh, well, that’s the question, really.

When I first started writing novels, I did. And then I discovered that they boxed me in. Because no matter what I put on the page as where I was going, as I got into the book, things happened that I wasn’t expecting and weren’t on my outline. I’m more like what they call a pantser, flying by the seat of my pants, I like to think of it as flying into the mist. I know where the book is going. I have to get to know who the characters are. And sometimes the characters say to you, “I’m not going there.”

More like sailing into the mist on this book, I guess, instead of flying.

Exactly. I didn’t know that that he was going to have to rebuild a boat. I didn’t know he was going to have these oracular dreams. Once Tachyon said they wanted it, I knew that I had to have a fantasy element that had never been in it to begin with. So, what did I do? He finds a bone, which is a whalebone jaw, and when he leans against it, he has dreams. The first dream is of a whale telling him about how the whales have been dying and why and how things are changing. And then, the next three dreams are about the boat that his father died on. So, I read Moby Dick, annotated it, and talked to Peter about it over and over again. Some people really need to fill out, you know, everything about their world and everything about where they’re going and know everything bit by bit. That’s not how I work. Now, having said that, I just finished another middle-grade fantasy novel called Sea Dragon of Fife. And it’s part of, I think, a series that’s going to be called—we’re still fiddling with this—The Royal and Ancient Monster Hunters, so it’s R&A Monster Hunters. And in that, because I first outlined it years ago when I still thought I could outline, it turns out that stuff that I put in later changed the ending, made the ending more poignant, because as I was going along and writing it, I realized . . .these are some kids who are out there as monster hunters, they’re school kids. And the head of the group is the schoolmaster. And we’re talking 1900s, Scotland. And they’re in danger, but they’re out there to kill the Sea Dragon. The Sea Dragon’s female. They’ve already killed one of her sons, may have killed the second one, and then they finally come upon her and everybody thinks that’s fine and I’m going, “Wait a minute, wait a minute, they’re killing a mom. You have to say something about this,” and that changed the dynamics when I have the main character, who’s telling the story, saying that she feels bad about this, so she has some real criticism. Meanwhile, you know, it’s a dragon that’s tried to eat two boys and may have killed other people. So, it’s a dragon, doing what a dragon does to feed its family. So that was not in the original outline and it changed things very much.

So, what does your actual writing process itself look like, then? You’re not referring to your outline all the time and then writing things. Do you—I always ask this—do you write longhand under a tree with parchment and a quill pen or do you work set hours during the day? Do you work in your home? Do you go out? Well, not now, but have you sometimes gone out to other places to write? Or how does that work for you?

I have a fairly simple thing. I get up in the morning, I go into my writing room, still in my jammies, and start to write, and write for about an hour. It may just be, at the beginning, just looking at my email, playing a little bit of Boggle, writing a new poem, because I send out a poem a day to subscribers. And then I go downstairs, have something to eat, go back upstairs and get dressed for work as if I were going out to an office. The office is right there in my house. And then it’s butt on chairtime that I teach my students all about. Butt in chair. If you’re not there working and you’re looking for an idea and the muse comes by, she’ll give it to you. But if you’re not in your chair, she’s heading out, you know, out west to give it to someone else. And I literally, I probably work between four and eight hours a day. Some of that is just reading, some of that is writing, some of that is revising, some of that is sending stuff out. But I’m at my desk. You don’t write four hundred books if you don’t sit at your desk, and it’s been an adventure.

I mean, it’s not that I don’t go out and do things. I have a house in Scotland that I go to and I’ll write there as well. Peter and I are right now sitting in his house in Mystic, Connecticut. I was writing this morning and I do other things and I’m a very personable kind of person. I like to see friends and take walks with them and talk business with them. Or if they’re not in the children’s book field, the children’s book world, or just the writing world . . . I have many friends, a huge number of friends, who are artists. I’d love to go to their studios and see what they’re doing. But I’m always a good part of my day writing. Less time at a conference. And interestingly, the stuff that I do when I’m in my jammies feels like fiddling. But when I’m dressed for work, I mean, looking like I’ve gone out of my business clothes, that’s when I do my best work.

That is interesting. I mean, everybody approaches it differently, that’s one of the interesting things about this podcast, is getting these different approaches that people take. Do you consider yourself a fast writer or slow writer or somewhere in the middle, or how do you typify yourself?

Well, you have to say fast, given how many books I have out, but each book is different, some books practically write themselves and other books, you’re banging your head on the wall. But I am a very fast rewriter. If somebody takes the book and it needs some work still, that’s where I put all my energy until that until it’s done.

Well, that’s the next thing I was going to ask you about was the revision process. So, when you have a complete first draft, do you go back to the beginning and revise before you submit? Do you use beta readers? Beta readers are all the thing right now, I’ve never had them, but I know lots of authors talk about that. And you did mention that your husband had read your book to help you with the sailing and so forth. How does all that work for you?

Well, I first of all, even if it’s an adult book, I read it out loud. That comes from all of my work and children’s books. I always read stuff out loud and that makes me hear things that . . . I have a little sign near my desk that says the eye and the ear are different listeners. If you are reading your own manuscript, you can elide, if you’re not reading out loud, so that you miss stuff, you miss the bad stuff. And if you are reading it out loud, then you are going to hear everything that doesn’t work. I’m a good reader, so I can sometimes almost even convince myself that a line works when it doesn’t. But I’m a line-by-line reader out loud. Then I go back and I will . . . with a picture book, I might revise it five, six, eight, ten times before I ever send it out. With a novel, I probably do two really solid revisions before I ever send it out. The longer pieces, and that includes . . . I have, actually, beta readers. Peter is one. My daughter, Heidi Stemple, is another one. And then I have other readers when I’m in Scotland. My friend Debbie Harris reads for me because I think that as much as I know about writing and as much as I know about editing, there’s nothing like a new eye to look at it and say, “I didn’t get this.” The connection was in my head, but I never got it down on paper. So, I really like having those beta readers. Every time, though, I choose somebody who has written something, who has published something, I think that that they are willing to be fierce and I need a fierce reader.

Yes, if, you know, if you give it to, in my case, say my mom or somebody, and they said, “Oh, that’s really nice,” that’s not helpful. You want people to say, no, I didn’t understand what was going on on page 37 and why your character did that stupid thing and all that kind of stuff. The big criticism is actually much more helpful than just than just praise.

That’s why I choose writers. All my children are writers, published writers. My friend Debbie is a well-published fantasy writer living in Scotland. So, there’s that professionalism that says, “:I’m not going to just say nice things about you.” My kids send me stuff for me to read that they’ve done. And I’m very honest with them. From the beginning, when they first started writing, and they would leave little things for me to read on the mantelpiece, I would say to them, “Do you want the Mommy answer or do you want the editor answer?” And they would say, “Oh, we want the editor.” And this is before they were published. I’d say, “First, I’m going to give you the Mommy answer. The Mommy answer is, ‘This is wonderful. Oh, you are such a good writer.’ Now, here’s the real truth from the editor. It’s very good. It still needs work.” So, since I was always honest with them, they’re very honest with me.

When your work does get to an editor, are you still getting, “This is very good, but it needs work,” from editors even at this point in your career?

This is what I’m getting a lot from editors. They will say to my agent, if I haven’t worked with them before, they will say to my agent, “Is Jane willing to work on this?” And I think to myself, “They think tjat a person who has done as many books as I have, would not work with that, would not be revising it?” It sort of makes me stunned. Who they’ve been working with? Of course, I’ll revise. I just recently revised something that an editor liked but still had some problems with. And I sat down and thought about what she said for about a week and a half. And then I said, “She’s absolutely right.” Then I rewrote it. And it’s much better. Will she take it? I have no idea, but it’s much better. And so, somebody will take it.

My editor, my main editor, is Sheila Gilbert at DAW Books, and she’s just wonderful for for pointing out those things that, “Yeah, I can make that better. You’re absolutely right.” And editors do that for you. It’s really quite wonderful to have an editor. And I wanted to ask you about the differences between writing for middle grade, young adult, and adult. Are those just . . . you know, to a certain extent they’re kind of just marketing categories, I guess. But there are . . . do you feel there are distinct differences among those three beyond just the age of the characters?

I think that that in some ways they sort of glide into one another, it’s true. And if you realize that the term young adult had not even been invented until the early 1960s when some somebody figured out that, “Oh, we can get an extra sale out of this if we put it in into that category, as well as perhaps also selling it as an adult book.” And many books are considered young adult/adult as crossover books. In fact, I think there’s now an actual crossover designation . . .

New adult, they’re sometimes called. New adult. Is that the term?

Exactly. That’s the term. So, the problem is in the, not in the book itself, but in the age of the main character. If you have a main character who is fifteen, sixteen, it’ll be nicely read by the younger ones and the young adults. If the character is twelve, thirteen, then a lot of young adults will not look at it. Adults will, but young adults will say, “I’m more interested in kids my age.” So, a lot of times you sort of weasel out of it. You either don’t say how old they are or you put them in exciting enough places that that anyone will want to read the book. I was . . . as I said early on, I was, as a child, reading books that were way over my head. And kids who reads at a very young age will do that. But a lot of young adult readers are really very happy just reading about themselves. I think the middle graders who are still trying to figure out what it is they would like to read, how far up they’d like to read, are the ones who are more flexible. And I think the adults are the most flexible at all because we’ll still read about kids, we’ll still read about Alice in Wonderland, we’ll still read about Huck Finn, and they’re not our age anymore. But we will also read about older people.

The problem is in the packaging. Because I did a book a few years ago with Midori Snyder called Except the Queen, and the two main characters were middle-aged. They were old fairies who have been kicked out of Faerie for spying on the queen, and so they no longer have the magic that keeps them young. So now they are on the high side of middle-aged. And there were two younger characters in it. They’re not the main characters, but guess who is on the cover? Not the main characters. The young woman who is one of the minor characters was here, and when we complained, they said this is the best cover for it, nobody’s going to buy a book with two elderly women sporting around. That’s the problem. Not the readership, but how they market the book.

Do you have a preference out of all the various age levels you’ve written for? Do you love writing in all these various niches equally?

My sweet spot is short. Meaning poetry, picture books, short stories. Or a short novel, but I have written a number of longer novels, which I’m very proud of, and it’s just that they go on and on and on and on for four or five years. That’s when I get tired of that, even if I’m doing my best work. So, I think I have a very short attention span. And a very short boredom span.

We’re getting within the last 10 minutes or so here, so I want to ask my big philosophical question. There’s three. The first one is, why do you write? The second one is, why do you think anybody writes? As human beings, why do we write? And then the third one is, why write stories with fantastical elements in them? So, start at the beginning. Why do you write?

Because I can’t, because I have stories in my head all the time. I go to bed, I dream stories, I wake up, I remember parts of those stories. Sometimes I could use the parts, sometimes I can’t, which is frustrating, but I am never without ideas for books. In fact, I give ideas away to other people.

I get that a lot, actually, from writers who will say, “I can’t not write and it’s almost a compulsion.” I think there’s very much an innate writer . . . I don’t know if it’s a gene, I guess it’s related to some sort of genetic component . . . to people who become, at least become writers who are, you know, published and read and write at that kind of level. I’m reading to my wife Robertson Davies’s collection of posthumous essays . . . I always forget the name . . . The Merry Heart, it’s called . . . and he writes quite a bit about this topic and about being a writer and writers being almost born as opposed to made. Anyway. So, why do you think a lot of us write? Why do you think human beings write? Why do we tell these stories and put them down in words and share them with other people?

Partially because it gives pleasure, partially because it gives information, partially because it gives a new way of looking at something, but partially because human beings are, more than anything else, good liars. We make ourselves look better. We make our children look better. We tell stories about our family that make us look great. We boast about things. It’s a human failing that’s been turned into a human success, I think. We laugh in our family and say all Yolens, all of the Yolens we know, are good casual liars. They tell stories. They are funny, they make up stuff, but only our side of the family and one or two others, sort of outliers, became passionate storytellers. My great-grandfather, I think it was, had an inn in the Ukraine, and he loved, not the work of being a being an innkeeper—that he left to the wife and kids in the hirelings—he would sit by the fire and tell stories. And he used to tell stories that he knew came from somewhere else, but he passed them off as his own. So, he told a Yiddish version of Romeo and Juliet, which was his big piece. Now, I don’t think he ever told anyone that Shakespeare had written the story.

Well, Shakespeare probably got it from somewhere else, knowing Shakespeare

Exactly. We’re passing wonderful lies on.

When I was a kid . . . there’s a famous Canadian writer named W.O. Mitchell, who actually spent part of his childhood in the town I grew up in in Saskatchewan. And he had . . .there was a TV show on CBC, which were . . .I guess they were his stories, I don’t know, he hosted it anyway, dramatized stories. And the name of it was The Magic Lie. That’s what he’d like to call writing: the magic lie.

And that works for me.

And then the third part of the question, you have, of course, written stuff that doesn’t have a fantastical element, but you have also written a lot that does. So, why include things that are completely fantastical in these stories that we like to tell people?

Because people have been doing that forever. They’ve told folk tales and fairy tales and tales of magic and wonder. We all know we’re going to die. So, we make up these wonderful stories of what happens after, before, during, which we all hope that we will have wonderful weddings and marriages to a prince, probably, you know, a king, possibly. We want to change lives with our stories. I think those of us who write for children have a better chance of that than anyone. Once in a while, you’ll get a book that, you know, like Silent Spring, that will change a great many lives. Normally, adult books don’t change lives the way children’s book change lives, because we’re taking someone who has not yet fully constructed themselves. And the stories that we tell help them think in different ways, shape them.

I’m very aware of that. I mean, I get letters from children all the time and I and I meet grownups who say to me, the grandparents, you know, they say to me, “I read your stories all the time to my grandchildren because they were the stories I grew up on.” That makes me feel really old when they say that. But it’s true. Those are the stories that we carry with us into adulthood. And they have, for whatever reason, shaped our lives.

Certainly, the ones I read shaped mine, that’s for sure. I still remember the ones . . . you know, the stories I read as a kid are the ones that really stick with me far more than what I’ve read since as an adult. So, we’re just about out of time, so let’s find out, what are you working on now?

Well, The Sea Dragon of Fife, which is a short novel. I have a book of poems about the Jewish experience and the Shoah coming out called Kaddish. That’s for adults. I’ve written two books with one of my daughters that are being published, one that I wrote with her when she’s ten, and she’s now in law school, and the other we wrote after she said, “Oh, I’m so excited about selling this book. But, you know, I’m really going to be a lawyer.” And the next morning she had the start of a manuscript on my desk. So that’s it. Yeah, right. “OK,” I said, “stick to your day job, but you can write in the in-betweens.” So the one that’s coming out that she wrote with me when she was ten, which we have done significant rewriting since, I have to tell you, is called Nana Dances and it’s a picture book. So, it’s full of pictures and it’s all about the various nannies who dance with their children and boys, girls, different people of different shapes and sizes and colors. And it’s, I think, it’s just a very sweet and lovely book. I have a bunch of easy reader books coming out, two of which are based on the interrupting cow joke that one of my granddaughters used to tell me every time I would visit. You know that joke?

No . . .

Knock-knock.

Who’s there?

Interrupting cow.

Interrupting cow who?

Did you hear me move in the middle of your asking? So this is a cow that nobody in the stable likes because she’s always telling that horrible joke and she ends up with a variety of outsiders who love what she does. So, everybody lives happily ever after. I’m on the fourth book now.

There’s more?

Oh, yes, there’s many, many more. I’ve sold a book called Bird Boy, which is being illustrated, and it’s a kind of semi-sequel to Owl Moon, which I wrote, which won the Caldecott. Let’s see, what else have I sold? I have to get out my list of about maybe fifteen, eighteen more books. I have about twenty manuscripts out there. I have about, in total, 130 unsold manuscripts that are rotating around there and I’m always writing something new.

People tell me I’m prolific and I’m realizing that I’m not. That’s very impressive! It’s been great, Jane, to talk to you. I guess your website is the best place if people are looking to find out more about you?

It’s certainly the most accurate because my son Adam, who is my webmaster, and I work on it on a regular basis. If you go anywhere else, you will find that I have written over one hundred books. You will sometimes find that I’m married to Adam, who is my son. You know, I don’t trust anything other than an author’s own website because we know most about ourselves. We know what’s current, what’s not covered.

And it’s just janeyolen.com.

That’s right.

Ok, well, thanks so much for for doing this. Jane, I really appreciated talking to you. I certainly enjoyed it. I hope you did, too.

I did a whole lot. Thank you.

And best of luck with every single one of your many projects coming up

To you, too. Bye bye.