Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

An hour-long talk with bestselling, award-winning science fiction author John Scalzi about how and why he writes, focusing on his latest novel, The Collapsing Empire.

The Introduction:

John Scalzi was born in California in 1969 and currently lives in Bradford, OH. He studied philosophy at the University of Chicago, which is where he began his freelance writing career. He wrote film reviews and was a newspaper columnist for a few years, and in 1996 was hired by AOL as its in-house writer and editor. He wrote his first novel, Agent to the Stars, in 1997 and published it free on his website in 1999. His first published novel, Old Man’s War, also appeared first on his blog (serialized a chapter a day) in 2002. Tor Books purchased it, publishing it commercially in 2005, and it went on to win the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer. Since then, John has won numerous awards, including the Hugo, the Locus, the Audie, the Seiun and the Kurd Lasswitz, plus the 2016 Governor’s Award for the Arts in Ohio. His work regularly appears on the New York Times bestseller list for fiction.

John Scalzi was born in California in 1969 and currently lives in Bradford, OH. He studied philosophy at the University of Chicago, which is where he began his freelance writing career. He wrote film reviews and was a newspaper columnist for a few years, and in 1996 was hired by AOL as its in-house writer and editor. He wrote his first novel, Agent to the Stars, in 1997 and published it free on his website in 1999. His first published novel, Old Man’s War, also appeared first on his blog (serialized a chapter a day) in 2002. Tor Books purchased it, publishing it commercially in 2005, and it went on to win the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer. Since then, John has won numerous awards, including the Hugo, the Locus, the Audie, the Seiun and the Kurd Lasswitz, plus the 2016 Governor’s Award for the Arts in Ohio. His work regularly appears on the New York Times bestseller list for fiction.

He also remains involved in the film and gaming worlds: he’s the creative consultant for the Stargate Universe television series, the writer for the video game Midnight Star, by Industrial Toys, and executive producer for Old Man’s War and The Collapsing Empire, both currently in development for television. He served as president of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America from 2010 to 2013. He’s married and has a daughter and “several pets.”

Website: scalzi.com

Twitter: @scalzi

The Show:

First, we establish that your genial host was literally the first person John met in science fiction and fantasy besides his editor, Patrick Nielsen Hayden: we were on a panel together at the 2003 Toronto WorldCon on the topic (if we remember right) of other ways to make money writing besides writing fiction.

John traces his interest in science fiction back to childhood reading, specifically mentioning Robert A. Heinlein’s Farmer in the Sky as one of the first SF books he remembers.

He notes that when, in his twenties, he decided to write a novel, “just to find out if I could,” he had to decide between two genres he was equally comfortable with, science fiction and mystery, and literally flipped a coin: heads SF, tails mystery. “It’s a weird sort of inflection point.” If it had come up tails, he wonders how different his life would have been, because “so many of the people that I know and like are in science fiction.”

He adds that SF is capacious enough you can write whatever you want, and he’s gone on to write a couple of what are essentially science-fiction mystery novels, Lock In and Head On.

John says he first realized he could do interesting things with words when, in sixth grade, a teacher asked him to write a letter to the news department of a local station because he wanted to get publicity for something he was doing and thought a letter from a student would get more attention than he would. He told John, “I want you to do this because you are good with words.”

In his ninth-grade English composition class, tasked to write a short story on the theme of gifts, he trashed what he’d first attempted and ended up, late on the last night, typing up a lightly fictionalized true-life story about his friends getting together: the gift they gave was their love for each other. (“Awww…”)

When that story, which he had slammed together at the last moment, was the only one in three sections of the class to get an A, he realized writing was something he could do well and relatively easily, whereas everything else–math, history, whatever–was difficult. And so, at the age of fourteen, he decided, “That’s it, I’m going to be a writer,” largely driven by the principle of least effort for maximum return. “The disappointing thing for me later was to find writing isn’t in fact easy, that you do in fact have to work at it, by then it was too late.”

He adds, “I have no other skills. The only other thing I would be good at would be Wal-Mart greeter.”

He kind of fell into his philosophy degree (he was undecided, but discovered he’d taken enough philosophy courses to graduate sooner than if he’d gone for, say an English degree), and agrees it doesn’t have a lot of real-world utility, but feels it has had value in his work. He says philosophy teaches you how to learn, and how to think more deeply about things, useful in writing science fiction.

He adds, “We like to call science fiction the literature of ideas, but I think really what it is is the literature of consequences. It’s not so much about the aliens arriving or robots coming, but the consequence of those arrivals that we write about in science fiction.”

Fun fact: Saul Bellow was briefly John’s thesis advisor.

John says coming up with ideas for novels aren’t the hard part; the hard part is distinguishing the good from the terrible. If he has an idea, he doesn’t write it down. If he remembers it the next day he thinks about it some more. If he remembers it in a month, even more. “It’s a vicious process because I’m absent-minded and forget a lot of things. For something to stay in my brain, it has to interest me.”

What interested him and led to The Collapsing Empire was the importance of ocean currents and the jets stream to European colonialism between 1400-1800. If those currents had altered, making it far more difficult or important for Europeans to sail to other continents, he wondered, “What would have happened to European colonialism, and consequently the rest of thew world?”

He gives a synopsis of The Collapsing Empire, which is about an interdependent network of worlds that rely on a natural phenomenon called the Flow, which permits interstellar travel. The Interdependency (as it’s called) finds itself in serious trouble as the Flow begins to collapse, cutting worlds off from the rest of humanity. “When humans are confronted with natural things that actually don’t care about human’s plans one way or the other, how do they dal with that?” He notes that has parallels in both the past and the present.

John begins building characters from archetypes. He knew he needed someone at the very top (the emperox, Cardenia), someone at eye-level (the scientist, Marce, a.k.a. “exposition guy”), and a “wild card” (Kiva). Once he knew he needed those types of characters, then he began to develop their personalities.

“I’m a huge fan of all the characters, which is nice because I had to write them.”

He notes writing Kiva in particular was “a heck of a lot of fun,” although you have to be careful or characters like that can take over the book. “Characters like Kiva are the spice, rather than necessarily the main dish.”

I noted that his approach to developing characters seemed filmic–starting with archetypes, working down–and asked if his long interest in and observation of film ties into the way he plots and writes.

John said, “Absolutely.” He notes Old Man’s War very clearly has a three-act cinematic structure, because that was a storytelling grammar he was used to not only from watching films but from analyzing them during more than a decade of writing film criticism. “In many ways my storytelling school was not really novels, it was film.” He also notes that his novels are “dialogue-heavy,” something else that comes from film.

He doesn’t anticipate writing any of the scripts for the Old Man’s War and The Collapsing Empire TV adaptations, since he doesn’t have any concrete experience in the field. However, he notes his experience as a reviewer, and hence familiarity with other screen adaptations, has made it easier for him to talk to producer–unlike some authors, he understands that the filmic version of a story and the novel version are very different, and changes have to be made to make the former work as well as the latter.

Adaptations shouldn’t be slavish, he says, but should be “intelligent,” leveraging “the strengths of the film medium to tell the story in a way that lives in that particular medium.”

He has written a screenplay adaptation of his novella The Dispatcher as an exercise and has received positive feedback on it, and does hope o write a script or screenplay in the future.

There is a brief aside about the alien lifeforms making mewing noises in the background.

Asked if he rewrites, John says, no, not in the sense of finishing a draft and then rewriting it from the beginning: he does “rolling rewrites,” so when he gets to the end, he’s done.

Two reasons: as a former journalist, “where you have write a couple of thousand words every few days and it’s all due at 3 p.m. and you have to write clean copy,” he learned to organize his thoughts as he wrote.

As well, he says, he thinks the revision process is dictated by the instruments people use. Those who write, or first wrote, by hand or typewriter, tend to do drafts. He’s only ever written on a computer, hence the rolling (or “fractal”) drafts. “By the time I get to the end, so much of what would have been first drafts or second drafts has already been subsumed in the writing process.”

He does a lot of research, but the Internet makes that “super easy.” He adds, however, that, “You have to be intelligent about it.”

Asked to comment on the concept of “worldshaping,” versus “worldbuilding,” he says that when writers create worlds what they are really doing is taking what they already know, introducing new highly speculative (and hopefully interesting elements), and then mashing them together to find out what comes out the other end. , mashing them together, finding out what comes out the other end.

” I would say I think both terms are equally applicable. I think the issue here might be degree than kind.”

He notes that, not only is it very difficult to create a completely new world, it would be a very hard book to sell, because there would be no hook there for the reader…and that’s important, because science fiction and fantasy writers are working “more or less in service to a commercial genre.” Writers have to think not only about what they want, but what editors and readers want.

“There’a reason why McDonald’s is hugely popular and molecular gastronomy is basically a niche project,” he says. “The number of people who want a hamburger is larger than those who want to question the nature of the food on their plate, and whether it is food or not.”

He points out that Old Man’s War is “Starship Troopers with old people,” a Heinlein juvenile with senior citizens. That was intentional, he says. He wanted to write a book that would sell, so he looked at what was popular at the time, which was military science fiction. So he decided, “I’m going to write a military science fiction book on my terms. I’m going to give people what they want, and then I’m going to give myself what I want, and then we’re going to see what works out.

Asked why he writes–or anyone writes–he says that self-expression is obviously the desire for all writers, but after that “things get varied very quickly.”

” I never once wrote in a journal,” John says, even though people gave him journals as he was growing up, thinking he was the kind of kid who would keep one. But, he says, “I already knew what I was thinking. I didn’t need to write it down.”

Instead, he says, he only started writing when he had an audience. “For me, writing has always been an extroverted act, not just for myself, but primarily for other people to read.” The gratification it provides comes from the ability to make people feel things through the power of words: to persuade, and argue.

John says a lot of people start writing because they love the act itself, but for him, that’s a small component. He notes that he plays guitar just because he enjoys it, and takes photos for the same reason. But, he says, “Writing for me has always been about making a connection with other people, and not just making a connection…but influencing them in a particular way, making them laugh, making them cry, making them get angry when I feel angry.”

He says his writing has had an impact on the real world. Some things in his stories–like the enhanced artificial blood in Old Man’s War–has piqued the interest of real-life scientists. SF offers something few other genres do, he notes, in that people sometimes read about something in SF and think, “This is cool, I want this in the universe,”–and then they go out and build it.

His biggest impact has been through a couple of non-fiction pieces, he says. His essay “Being Poor,” written in response to people wondering why those affected by Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans didn’t just pack up and leave, “went everywhere.” It appeared in newspapers, it’s been put in textbooks, and it’s taught in classes. “That’s an example fo something I’ve seen go far and wide and have influence on the discussion.”

Another was an essay comparing life to a videogame, and arguing that in that metaphorical videogame, straight white men play at the “lowest difficulty setting.” It doesn’t mean they can’t still lose, it doesn’t mean the game is hard, but it isn’t as hard for them as for some others. He says that piece was an attempt “to explain privilege to people who hate the world privilege.”

He says that piece has also gone everywhere, and he hears people using that metaphor whom he’s quite certain have no idea that it originated with him. “it’s come into the common parlance when discussing privilege and intersectionality.”

John says it’s harder to say if anything he’s doing in SF will have any significant influence. “I don’t think you get to figure it out until you’ve been doing it for twenty or thirty years.” And, he adds, “If you’re sitting there saying, what abut my legacy, you won’t be focusing on what you’re doing now, which is writing stuff that is interesting and entertaining and makes people think today…you sit there and write the best work you can. If it gets remembered, that’s great, if it doesn’t, that’s fine, because right in the moment you are doing what you’re supposed to do, which is make people laugh, or cry, or think, or be entertained, and that in and of itself is a laudable goal.”

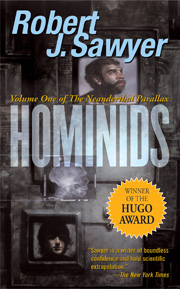

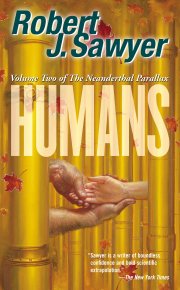

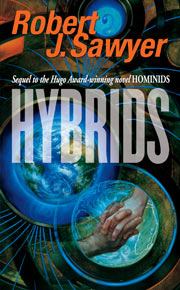

Robert James Sawyer is a Canadian science fiction writer, born in Ottawa and now living in Mississauga. He’s the author of twenty-three novels and innumerable short stories (well, not literally, obviously they’re numerable, but it’s a large number), and is the most-awarded science fiction writer of all time, said awards including the

Robert James Sawyer is a Canadian science fiction writer, born in Ottawa and now living in Mississauga. He’s the author of twenty-three novels and innumerable short stories (well, not literally, obviously they’re numerable, but it’s a large number), and is the most-awarded science fiction writer of all time, said awards including the