Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

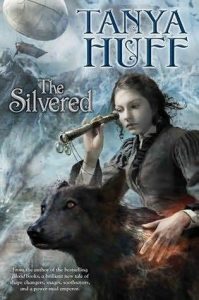

The second episode of The Worldshapers features the talented and popular author Tanya Huff, with a special focus on her Aurora-Award-winning novel The Silvered.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/tanya.huff.5

Twitter: @TanyaHuff

The Introduction:

Born in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Tanya grew up in Kingston, Ontario, and made her first professional writing sale to The Picton Gazette when she was ten. They paid her a dollar for every year of her life, for two poems.

Tanya joined the Canadian Naval Reserve in 1975 as a cook, serving for four years, then attended Ryerson Polytechnical Institute in Toronto, obtaining a Bachelor of Applied Arts in Radio and Television Arts alongside Robert J. Sawyer—my very first guest on this podcast.

In the early 1980s she worked at a game store in downtown Toronto, and from 1984 to 1992 she worked at the science fiction bookstore Bakka. All the time she was writing—seven novels and nine short stories, many of which were subsequently published. Here second professional sale was to George Scithers, then editing Amazing Stories, in 1985: “Third Time Lucky.” Presumably, he paid her more than a dollar per year of life.

In 1992 she moved from downtown Toronto to rural Ontario, where she continues to live with her wife, Fiona Patton, also a fantasy writer, along with many pets.

Her diverse array of fantasies range from the highly popular “Blood” books, which mix vampires, fantasy ,and romance and were the basis of the TV series Blood Ties, to the Torin Kerr military SF novels, and the humorous fantasies of The Keeper Chronicles. Her publisher is DAW Books, and in the US alone, according to her agent, more than 1,200,000 copies of her work are in print.

The Show:

Although we’ll be discussing her book The Silvered, we actually start with a discussion of her (and my) interest in theatre.

Although we’ll be discussing her book The Silvered, we actually start with a discussion of her (and my) interest in theatre.

Then we move on to a discussion of her early writing. Although her first published poems were “ten-year-old angst,” she says she was interested in fantasy from the beginning of her reading career.

The first two books she remembers checking out of the library were Greek Gods and Goddesses, “which was almost as big as I was,” and The Water-Babies, “a weird Victorian choice” about a boy who runs away to join the water sprites that live in the pond at the bottom of the garden. “Cleanliness is next to fantasy, apparently.” It also featured a heavy dose of morality.

Even earlier than the 10-year-old-angst poems, Tanya (at age three) dictated a letter to her grandmother to send to her father, then at sea in the Navy, featuring a story about a spider who lived in the garden. Tanya also did the illustration, without notable success: the spider looked more like a pom-pom, eight legs apparently being too challenging for her three-year-old hand.

One summer when her cousin had an operation for scoliosis and spent weeks in a cast, she told her stories to help her pass the time. As well, Tanya says, “At recess, I was always the one who directed the games.”

She says she stumbled over science fiction by accident. She had run out of things to read in the children’s section of her local library (the upstairs) and was deemed too young to be sent into the adult section (downstairs). But when she started in the As and began reading everything in order, they decided maybe she could go downstairs. There she discovered little yellow stickers with rocket ships on them, the marker for science fiction novels. “I picked up everything with a rocket ship on it,” she says.

Her Grade 7/8 school library had all of the Robert A. Heinlein “juveniles,” plus the books for young people by Andre Norton and Isaac Asimov. “I just ploughed through all of those.” The first Andre Norton book she read was Year of the Unicorn, and it made such an impression that a few years ago she bought a first-edition copy of it.

Tanya says the first complete fiction she wrote was when she met a girl in Grade 9 who was writing pastiches of Zenna Henderson. “It was the first time it occurred to me that people wrote books. (I have no idea where I thought they came from before that.) I thought, well, if people write books, I’m a people, I can write books.” So in short order she wrote a western, a spy novel, a science fiction novel called Light Years, and a book called: Richard the Lionhearted Was an Overmuscled Thug, or the Facts Behind Robin’s Merry Men. She says she also illustrated them, albeit with little more success than she had illustrating the spider story when she was three. Illustrated them.

Her friend Karen and she created the Insult Your Intelligence Book Club. They wrote the books on paper with carbon paper underneath it, to create two copies.

Despite her interest in writing, it didn’t occur to her it could be a career. Tanya notes she comes from a working-class family: she was the first person in her family to graduate from high school and the only person who had ever gone to university. “Writing books was not something one saw as a career,” she says, and notes her grandmother was much more thrilled the summer she got a job as a Teamster, a good strong union.

After her four years in the military, she went to Los Angeles to become a TV writer, but, she says, she was “too Canadian”: when she ran out of money (in about four months) she packed up her typewriter and came home instead of getting an illegal job, even though she had an in with the company producing the TV series Operation Petticoat. “If I had had half a brain I’d be running the CW right now.”

Instead she decided to go to Ryerson, because she’d discovered “there’s a hell of a lot of money in television programming, and I wanted some of it.”

At Ryerson she had three years of scriptwriting. She notes she’s always been a visual writer, so she had less trouble writing scripts than some text-based writers. “Rob Sawyer and I did our third-year project together. In retrospect, it might have been better if instead of two writers we had pulled one of the tech guys in.” She also had a creative writing class with Rob, although she was writing science fiction and “the teacher absolutely did not get it. I had to explain everything to her.”

She actually started writing Child of the Grove in her TV tech class, “which could possibly explain my mark in my TV tech class,” but she started writing seriously at novel length “with intent to be published” while working part-time at Bakka books: the part-time job gave her time to write. Her first short story sale came at about the same time DAW Books was looking at Child of the Grove; editor Sheila E. Gilbert asked if she had anything published previously, and she was able to say she’d just gotten a letter from George Scithers.

She’s been at DAW her entire career, and sees no reason to leave. “They’re wonderful people. I’ve always said if Sheila retires, I retire, too.”

The Silvered was pitched as “the Napoleonic Werewolf Book.” It deals with the transition point between the manners and mores of Regency England and the Victorian era, with its greater emphasis on technology. “Werewolf culture is essentially Regency England, the opposing culture is essentially Napoleonic.”

But ultimately, “like all of my books, it’s a story not so much about, ‘Who am I?’, but ‘Who do I decide to be?'”

Tanya says the The Silvered “was one of those books you have kicking around in your head for a long time,” one with a “long gestational period,” and partlly arose from the fact that she loves Georgette Heyer, like many fantasy writers do, “probably because she pretty much wrote a fantasy version of the Regency,”

It wasn’t a book with “one big solid idea” that can be encapsulated in an elevator pitch, but more a lot of little things building up over the years. Tanya says in a lot of her books (like the Blood Books) each book deals with one idea thread. In The Silvered, she was dealing with many little things, and not just one big heavy thing–but she figures she did it well because “it’s the only book of mine that’s ever won an award” (the Aurora Award for Best Novel).

When she writes, Tanya says, she knows where she’s going but she doesn’t always know how she’s going to get there. “I have the beginning, and then the end, then I travel my characters through it. I try to look at characters to build them up like you would meeting a person for the first time. You observe what they are like, over the course of the book.”

She notes that for The Silvered she put the characters into groups. There was the redemption character, the young hero, the old hero, the young heroine, the old heroine. The complexity of the multiple characters and situations mean she created more story structure than she usually does: she says she’s usually much more of a “pantser” than she was with this book.

While she can outline if she has to (she did a work-for-hire book in the Ravenloft series for TSR that had to be very strictly outlined), one of the advantages of having done 32 books with one editor is that she doesn’t have to outline anymore to sell a book.

For The Silvered she spent a full month doing nothing but research notes, handwriting them, because she finds when she handwrites things, they stay in their head, whereas if she types them, “it’s just typing.” Since she knew where the story was located, she had pages of notes on the geography, botany, climate, and more. While writing, she sometimes looks for specific things like how long it takes a person to walk twenty-five miles, although she notes you have to beware the “Wikipedia rabbit hole,” where “suddenly you find yourself researching cornbread in Central America.”

She had to spend a lot of time thinking about werewolf society, things like clothing (which has to be easy to get out of), the lack of a nudity taboo or body modesty, the fact furniture is chewed up (“because, puppies”), and more.

Tanya says she’s very much a “one thing at a time” writer: if she’s doing a short story she has to stop working on her latest novel, because otherwise “they would both sound exactly the same.”

Speaking of voice, for The Silvered she pulled out all of the sections from each POV character so she could keep their voices consistant.

Humour is always a part of Tanya’s book, although she notes that the Keeper Chronicles, which are meant to be funny, were the hardest thing to write.

We spent some time talking about an apparently minor incident involving a rabbit, which proves in fact to be major foreshadowing of something much more significant later on. Tanya said as soon as she got to the rabbit she realized how what happened to it could resolve the greater issue later on. (Those who have read the book will understand these vague references.)

Tanya says her first draft is probably 80 to 85 percent of what is actually published, then she layers it up from there. She compares this to contractors, who build a house layer by layer. There are other writers, she notes, who are more masons building a wall: pull out one brick at the bottom and the whole thing collapses.

For Tanys, Sheila Gilbert’s feedback is usually to add more detail. She thinks this may relate to the fact that her actual writing training is in television, where details are put in “by the other 75 people who work on the property.” She says she’s worked so long with Sheila she can hear her voice in her head when she’s writing.

Tanya claims to be terrible with titles: The Silvered took a two-hour discussion with Sheila to settle on.

If she ever stops writing fantasy and science fiction (maybe because Sheila has retired) she has an idea for a series of cozy mysteries set more or less in rural Ontario, where she lives. The first book would be called Strawberry Fields. She’d also like to do “a lesbian Regency romance,” which she figures has bounced around in her head long enough she could probably write right now.

Why write science fiction and fantasy? “The cynical version is it’s the main income coming into the house and I’d like to make a living… the other answer is because you write what you love.”

She says SF and fantasy allow writers to look at the “heart topics.” In Touch Magic Jane Yolen has a list of these: things like sacrifice, duty, honour, love. She notes it’s not odd that those are at the heart of so much SF and fantasy, because when you put people in extreme conditions, it exposes what’s at their core. “Any genre is just telling stories about people to other people. It’s how you do it that is the difference.”

Tanya feels her work has touched a lot of readers. She notes that she hasn’t been at a convention in the past twenty years without someone, usually a young woman, coming up to her in tears, saying things like they had read the Quarter books in high school, and it was the first time they had seen themselves in fiction, the first time they had seen a bisexual character.

The chairman of WindyCon in 2016 told her that her Keeper books got him through his Master’s degree program when he was “falling apart in every other way,” she adds.

“That kind of response is better than an award. (Which is not to say I wouldn’t take a Hugo if someone offered it to me.)…I get so much emotional response back from people who have read my books that I feel very nourished by my readers.”