Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

A 45-minute chat with Cat Rambo, Nebula Award-winning author of more than 200 published short stories and several novels, editor, writing teacher, and past president of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, about her creative process.

Website

www.catrambo.com

Twitter

@catrambo

Facebook

@catrambo

The Introduction

Cat Rambo’s more than 200 published short stories have appeared in Asimov’s, Weird Tales, Clarkesworld, Strange Horizons, and many others, and consistently garner mentions and appearances in year’s-best-of anthologies. Cat’s collection, Eyes Like Smoke and Coal and Moonlight, was an Endeavor Award finalist in 2010 and followed their collaboration with Jeff Vandermeer, The Surgeon’s Tale & Other Stories. Their most recent collection is Neither Here Nor There, which follows Near + Far, containing Nebula-nominated “Five Ways to Fall in Love on Planet Porcelain.” Their most recent novel is Hearts of Tabat from Wordfire Press, Book Two of the Tabat Quartet. They have edited anthologies, including the political-SF anthology If This Goes On, as well as the online, award-winning, critically acclaimed Fantasy Magazine. The work there earned a nomination for World Fantasy Award in 2012.

Cat runs the decade-old online writing school the Rambo Academy for Wayward Writers, a highly successful series of online classes featuring some of the best fantasy and science fiction writers in the business, and has also taught for Bellevue College, Johns Hopkins, Towson State University, Clarion West, the King County Library System, Blizzard, the Pacific Northwest Writers Association, Cascade Writers, and countless convention workshops. And although no longer actively involved with the game, Cat is one of the minds behind Armageddon MUD, the oldest roleplay-intensive MUD (interactive text-based game) on the Internet. They continue to do some game writing, as well as technology, journalism, and book reviews.

A long-time volunteer with the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, Cat served as its vice-president from 2014 to 2015 and its president for two terms, from 2015 to 2019, and continues to volunteer with the organization.

The (Lightly Edited) Transcript

So, welcome to The Worldshapers.

Thank you.

You may not remember…we did meet, actually, at the SFWA table in San Jose, I think. I was volunteering, and you happened to come by.

Oh, nice.

Like I said, you wouldn’t remember, but I remember you.

Conventions become a giddy world for you when you’re SFWA president, unfortunately.

I’m sure. So, we’ll start, as I always start by taking the guest, you in this case, back into the mists of time, which…as I keep saying, especially when I’m talking to young authors, the mists of time is deeper for some of us than for others. But, how did you get…well, first of all, where did you grow up and all that kind of stuff? And how did you begin to become interested in science fiction and fantasy and in the writing of it particularly?

Well, I grew up in South Bend, Indiana, which is northern Indiana, and I was a child who read ravenously and early on discovered that I loved fantasy and science fiction. My babysitter was reading Tolkien’s The Hobbit aloud to me, and I began sneaking chapters on weekends when she wasn’t there. And at the same time, it was always assumed that I was going to write because I loved to read so much and because my grandmother wrote young adult novels, under her initials because they were sports novels. So, she was the author of such classics as Football Flash, Basketball Bones, and my favorite Martha Norton, Operation Fitness USA.

I’ll have to look those up. So, when did you start writing? I.

I started…when I was, I want to see nine or ten, I had a poem published. My grandmother had actually given me a book on writing, and I started writing poetry and sent something off to a contest. So, I was writing from nine or ten. After a fashion. Some of them were, I think, more story-shaped than others.

I always like to say that—because it’s true–that my first published work was in Cat Fancy Magazine when I was about 12 years old or something like that. They had something called Young Authors Open, and you could send stuff in. And it was a terrible pun about…they were looking for a replacement for Santa Claus, and they found this guy that looked like he’d be perfect, but the previous Santa observed him all year, and when he saw what his garden was like, he realized he could never be Santa because he wouldn’t hoe, hoe, hoe.

Oh, that’s cute. That’s awesome, though.

So, I think I got like fifteen dollars or something. So, my first professional sale.

I remember that magazine? So, yeah. Oh, that’s too funny.

When you started writing, did you…you had the poem, but were you writing other stuff, and were you sharing with other people? I always ask that because I shared my writing and with my classmates and so forth, and that’s how I found out I could tell stories.

I was. I had a story, a serial story that I was writing instead of actually practicing in typing class, because my parents and the parents of four of my friends enrolled us in summer school in typing class because they thought it would be good for us. And my act of rebellion was to actually write a long serial space opera that the other girls loved. And so, I did. I learned that people enjoyed my stories and kept writing them after that.

Did you write longer and…I guess, when did you start trying to get your stories published? I guess that’s the next step.

I had a few stories published in high school, usually connected to gaming, like, in gaming magazines. I had a couple of game reviews and book reviews and a terrible, terrible short story. So that, yeah, in high school pretty much.

Did you study writing formally at some point?

I did. I was one of those people who took a while to go through college, and so I dropped out and worked in a bookstore for a long time and then came back and actually dropped out a second time, just to make sure I was totally confused. But then, after I came back to college, I ended up going off to get a master’s in writing at Johns Hopkins, where I studied with John Barth and enjoyed myself very much.

I often ask people who did do formal writing training if it was helpful. And it sounds like in your case, it was.

Well, I think it was. But I also want to say that it wasn’t until I came to fantasy and science fiction that I got a lot of the nuts-and-bolts stuff. I felt like Hopkins was a lot of theory, which certainly is very useful, but it wasn’t until I got to Clarion West that we started talking about kind of, like, here’s the advantages of, say, first-person versus third-person. The more crafty sort of stuff.

And when the longer there, did you start making sales?

I…let’s see, I started selling stuff when I was in grad school, to small literary magazines, which meant I was making like five dollars or ten dollars a sale. And then I got kind of sidetracked and went into computers. And it wasn’t until 2005 that I sort of came back and started sending stuff out again, began sort of taking it seriously. And so, after about 2005, I started making some decent sales.

Yeah, well, I was interested in the writing, working in computers. My first books that I wrote were all these sort of basic computer manuals. My first book was Using Microsoft Publisher for Windows 95.

Then you will appreciate, that’s what I did, I was a documentation manager, and we were documenting VisualBasic.net.

And has any of that fed into your writing in any other way, the working on that side of things, has that fed into your stories at all?

Well, I tend to be more open to new technology and interested, particularly in new computer stuff, I think, than some other writers. One of the things I found, paradoxically, about science fiction writers is that many of them seem to sort of freeze at a particular technological level. And apparently, I haven’t encountered the one I’m going to freeze at yet.

When did you move on to the longer work, your novels?

I went to Clarion West, which is a local fantasy and science fiction workshop in 2005, and started writing a book immediately out of that, but it didn’t get published until eight years later. It went through, like, thirteen drafts and various convulsions. One of the jokes in my family is that I could never leave my husband because he’d read thirteen drafts. Which I’m not sure…we don’t need to tell him this, I’m not sure I would have done for him. I mean, can you imagine reading thirteen drafts of the same book? Holy crap.

I get tired of reading my own books, much less somebody else’s.

Oh, God.

Do you think that you’re…I mean, people do seem to specialize in one thing or another. You’ve clearly written more short fiction than long fiction. Do you think you’re more naturally a short-story writer than a longer fiction writer? Or do you even think that’s true, that people tend to be one or the other?

Well, I think they’re very different forms, and I think that they play to different strengths. One of the things I have to tell my students often is that a novel is not just sort of a bunch of short stories clumped together. It’s a lot more complicated than that. I think I’m good at both of them. I think I’m better at short stories. But I don’t want anybody to go, “Oh, shitty at novels. Why should I check them out?” Because my novels rock. Go buy them immediately.

Yeah, I was not suggesting that people not go out and…

No, but a good short story is, just can be, so pleasurable and so interesting and, at the same time not be the huge investment of time that a novel is, right? Depending on how fast you read, a novel can be a substantial investment of time, and a short story can be fit into standing in line somewhere.

Well, you’ve also done editing. How did you fall into that?

I was very stubborn about sending out stories. And so, I was sending stories to Fantasy Magazine, and at some point, the editor asked me if I was interested in, I think in reading slush, and then, was I interested in editing? And it was because we had done a lot of talking and I had been, I think, very persistent about sending him stories. So, I became the editor. I sort of fell into it. And since then, I’ve pursued a couple of projects. I’ve actually got a project coming up that I’m really excited about, which is going to be an anthology of near-future science-fiction relationship stories, because I think one of the things that science fiction has fallen short on is…often it’s very good at projecting what technology will change, but not so much on what the social dynamics are that will change.

What have you found…I mean, the editing I’ve done, and I’ve done a lot of…and so have you, you teach writing, and this will tie into that, too. But all that kind of working with other people’s work, how does that fit into your own work? Do you learn, you know, by…what’s that thing from The King and I, that by your students you are taught, if you become a teacher by your students you are taught?

Oh, you do. No, you really do learn so much. And I think that critiquing and editing other people’s stuff gives you some distance that lets you learn things that you might not from reading your own. But the other advantage of the school is that I go out and pursue teachers that I want to study with. And so, like, Seanan Maguire has done four classes for me now. I just got Henry Lien to do an awesome workshop that I’m very excited about. And so, I don’t just have the benefit of teaching. I have the advantage of, at least once a week, I’m sitting in on a class with someone world-class talking about fantasy and science fiction, and I count myself incredibly lucky.

So, despite all the teaching and everything you have published, you still feel that you’re learning the craft as well as teaching the craft?

Oh, absolutely. You’re always learning. It would be sad to stop learning.

Well, we’re going to talk about two things here. You have a…so, we’ll start with the joint project that’s coming up from Arc Manor, you and Harry Turtledove and James Morrow. James Morrow is going to be on the podcast; I’m talking to him in a couple of weeks, as well. So, tell me a little bit about that and how that came about and what your contribution to it is.

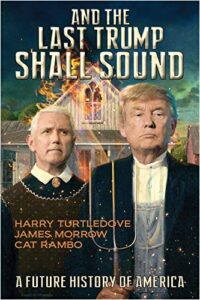

Well, A, how fricking intimidating, to write something with Harry Turtledove and James Morrow. Harry and I are Twitter friends, you know, and then we’ve met at a few conventions and talked back and forth. I’m a huge admirer of his work. And he said, are you interested in being the third in this project that Arc Manor is putting together? And I said, sure. And it was…I don’t know, it’s a really interesting project. The three novellas are incredibly different. I don’t know that you could find three more different pieces.

Three very different writers.

And Harry’s is very considered, and it’s full of quotes from Confederate history and civil war history. And you could tell he really knows his politics and stuff. So, I’m reading it, and I’m thinking, “OK, so this is what I need to do.” And then I read James’s, and James’s has a cross-dressing porn star persuading Mike Pence to do increasingly improbable things, and I’m just like, “Well, this is so like, OK, you know,” and so my story is, I just went in a completely different, different direction and went rather Black Mirror and depressing because I figured all the humor had been absorbed by James.

So, the name of the book is The Last Trump Shall Sound, is that right?

And the Last Trump Shall Sound. Yeah, it’s got a great cover based on that Grant Wood, “American Gothic,” Trump and Pence dressed up as that couple.

And that’s coming up in September, right?

It is coming out in September. And that was surreal. I’m going to say…I just did an essay about this. It’s coming out in the SFWA blog, where it was just weird. I had turned the novella in January, and I got the copy edits back a few months later. And I was just like, “Wow, the world has changed radically in the last three months.” And it was hard knowing whether to go back and insert some of the incredibly improbable things that had happened in the meantime.

Yeah, this is one of those years that should have been a science fiction novel about, oh, 1990.

Yeah.

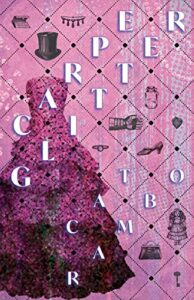

Except nobody would have believed it, so…and then the other one, and we’re going to use this one as kind of focusing on your creative process. You have the Nebula Award-winning novelette Carpe Glitter.

Mm-hmm.

So, for those who have not read it, can you give a quick synopsis?

Carpe Glitter is about a young woman who goes to sort through the belongings of her grandmother, who was not just a hoarder, but a stage magician. And in the course of sorting through not just one but three houses worth of clutter, she discovers a magical legacy that has influenced her family history in a way that she was not aware of.

OK, so how did this one come about and how does, more generally, I know this is a cliché question, and yet it’s a legitimate question…

It is a legitimate question.

…where do you get your ideas? Or as I like to say sometimes, what was the seed of this particular…?

What was the seed? So, with this one, it actually was the title. I was playing around with phrases, and I really liked “carpe glitter.” And I started thinking about what sort of person might have that as a life motto. And at the same time, I had been reading a book that was talking about hoarders, and I started thinking about that idea of kind of seizing the glitter and then never letting it go. And at the same time, there was a call for dieselpunk short stories. And so, I threw in a dieselpunk context and started writing from there. As far as where ideas come from, I find that the more that I am both reading short fiction and writing down ideas as they come to me, the more ideas come. It’s when I’m not reading or not paying attention to inspiration that things dry up.

I can’t remember who I was talking to, maybe it was James Alan Gardner, who said ideas are like neutrinos. They’re everywhere, but you have to be dense enough to stop them, or something like that.

I like to think of it as…your unconscious mind is a lot like a cat, and it will bring you small dead-animal story ideas as long as you are praising it. And if you are not sufficiently appreciative of the little bodies, then it will stop bringing them to you. It’s actually a pretty bad metaphor.

I like it. So, once you have your idea and you’ve decided you’re going to write this story, what does your plan…and this applies to all of your stories and also to your novels, because they often would take more planning, I would think. Are you an outliner, or are you more of a just launch right in and get writing…?

That is something that has changed a lot over the course of my writing career. And I used to be a total pantser, and now I’m much more of an outliner. But I also…I have, actually, a book called Moving from Ideas to Draft, which is about the fact that…I think ideas come in different forms. And the question I often get asked at conventions is how do I tell the bad ideas from the good ideas, by which people mean, you know, how do I tell the idea that I can turn into a story versus the one that I get halfway into and then abandon? And my theory is that there are no bad ideas. It’s simply that different ideas give you different things. And so, I have stories that started as titles. I have stories that started as characters. I have stories that started as, I want to write a story about how people carry grudges around with them and how it gets in the way. I have stories that have come about in all sorts of different ways, including just springing into my head full-fledged, which is very nice and does not happen half as often as it should.

Yeah, and sometimes…well, I have a metaphor I use sometimes, which is when you have that initial idea, it’s like you have this beautiful Christmas ornament and it’s perfect and round. And then you smash it with a hammer, and you try to get back together using words.

That’s perfect. That’s exactly what it’s like.

Because sometimes those ideas are, like, this is brilliant! And then somehow, the process of actually turning them into story can be a challenge.

The thing I always say to my students is, I used to be like, “Well, yes, sure, there’s some ideas you just, you can’t do anything with.” And then I read a story by Michael Swanwick, which basically is a story of people journeying across the surface of a giant grasshopper. And I was like, “OK, if Michael could carry that off, you can do whatever you like in a story,” because that is the dopiest idea I had ever heard. And he did it.

I always think of Cory Doctorow, who’s also going to be on the show, no too long from now.

Oh, awesome.

And, you know, he had the one with one of the characters was a mountain and one was a washing machine.

Was it, like, Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town?

Yeah, that was it. Yeah.

That was an excellent, excellent book. Yeah. Yeah.

So, once you begin writing, are you a straightforward start-to-finish, or do you write, especially in longer stuff, do you tend to write scenes and piece it together, or how does that work for you?

The longer the piece is, the more likely I am to write it as a sort of a creation of scenes. I just got…Beneath Ceaseless Skies just took a novelette from me. And one of the things I was very worried about, in fact, that it was that it had gotten written out of order. And I was worried that in the rewrite I had not made it, put it all in order. But apparently, I seem to have. So, yeah, it’s…and it’s hard. I just finished designing a class called “Principles for Pantsers,” which is basically about kind of like what to do when you’ve got these huge lumps where you’re just like, none of this makes sense. How do you untangle it?

That’s interesting that…you know, you’re teaching all these classes, and as I said, I’ve done some teaching as well, and I sometimes find that I will be telling, you know…I was writer-in-residence at the Saskatoon Public Library for nine months, this last September to May, although I was writer-in-residence in my residence for the last two and a half months of that, but anyway. And, you know, I’ll tell them something, and I’m all confident and, you know, this is this…and then I think, you know, if they look in that book of mine, they’re going to see that I didn’t actually do any about it. Do you ever feel that when you’re, a little of that, when you’re teaching writing, that, you know, that sometimes you don’t do what you teach?

Oh, every once in a while, yeah. Because I’m…one of the things I’m big about is, for example, is telling people that they need to build enough time into the writing process for revision. And I suggest that they put the story away for a week at least, and then come back to it. And of course, you do that because the story in your head and the story on the paper are, as you said, one is a Christmas ornament that is beautiful, and the other is much less beautiful. And I do try to do that, but I’m also aware that I am human, and I am prone to procrastination and there is always at least a few times each year where I am like, “Holy crud, this story is due tomorrow. Why is it not done yet? Oh, oh, oh, and then turn it in at the last minute.

I always think of the…I guess it was Douglas Adams that had the quote that he loved deadlines, he loved the whooshing sound they made as they rushed by.

And as an editor, you become aware of what a pain in the ass those writers are, right? And so, you don’t want to be that person. I just had a friend, bought a reprint from me, and she sent me an email that said, basically, “We cannot send this to the audio folks until you send in the contract,” and I was like, all right, that was a really smart thing to say, because if it was just sort of like, we’re not going to pay you till you get the contract, you know, it’s ten dollars. So, of course, I’m going to probably procrastinate because, you know, ten dollars. But when I know that I’m holding people up, I’m going to be much better about it. At least, I’d like to think so.

You mentioned the revision process. So, what is your revision process…first of all, do you do it all yourself? Do you use beta readers, or how does that work for you?

I try to use beta readers, particularly for longer work, and I do have a fairly structured process where I do try to put it aside, and then I read, I create a sort of plan of attack. I move the big, kind of look for the big-ticket items, and I try to sort of work my way in with finer and finer-grained edits because it doesn’t make sense to polish a scene if you’re going to cut it out. So, the line edits are the last thing, and then the read-out-loud pass, which has to happen, is one of the very last steps.

Do you find that you have certain things that you find yourself having to polish every time?

Oh, yeah.

We all have tics that…

Oh, yeah. One of the things I do, which your listeners may find handy, is if you run a word-frequency count, you will catch, for example, the fact that you had characters tilt their head twenty-seven times over the course of a single book. So, I look for that sort of stuff because, you know, sometimes it’s basically, your mind is just saying sort of “insert body language here” and you have defaults. And so, you stick in your default, and you need to go back and just sort of make sure that you aren’t constantly tilting your head.

Yeah, I saw somebody on Twitter today who was talking about writing, say, “Is there any way that characters…” I don’t know what he was reading, or maybe it was something he was writing… “where the characters express emotion other than taking deep breaths, taking short breaths…”

Yes. And you find yourself doing whatever you’re doing. I can remember writing a short story at one point, it was when I was a smoker, and I went back and looked at the draft and realized that I’d had the character light a new cigarette like every two pages and that they surely had an ashtray smoldering in front of them, just disgustingly full of cigarette.

Somebody asked me if my character was perhaps drinking too much and if I had a problem. But no, it was just, you know, again, it’s business to fill. Sometimes you need something for the character to do. And I said, you’re probably right. I should maybe not have her, especially when she’s, like, about to be interrogated or something. She probably shouldn’t be having that second glass, whatever.

Yeah.

I also find that my characters tend to make a lot of animal noises, like, they tend to growl dialogue or snarl dialogue. And I try to catch all that, although my most recent one has werewolves and vampires in it, so the werewolves, I guess, you know, they do growl dialogue. So then, once you have this polished to your satisfaction and it goes to an editor, what kind of editorial feedback do you typically…in short stories, it’s there’s sometimes a lot, sometimes a little. In longer stuff, you’re more likely to get more editorial feedback.

Some places I get no changes at all, or they’ll fix a typo or whatever, but, like, the novelette with Beneath Ceaseless Skies, I’ve just got a second round of edits from the editor, which is kind of, that’s actually outside the norm for there to be that much. But Scott Andrews is just super, super careful with the sentences. Plus, I think he has learned to explain things at length when he makes changes because he knows I will push back if I don’t understand the change. I love Scott, and just we really go back and forth on the edits, so that may be atypical. I think most of the time when you sell stories, though, there’s not that many edits.

And if they are, I mean, I think you probably run into this when talking to starting writers and some writers are worried about what an editor will do to their…

Oh, yeah.

…deathless prose. And I always say they make it better. Typically, they make it better. If it’s a good editor.

Yeah. And it’s so rarely…I mean, I can only think of a couple of times when I have run into an editor where I thought, “OK, they are they are not doing happy things to my prose.” And I think most of the time editors are also very good about letting you push back if you can say why you’re pushing back, and” because it’s my deathless prose” is unfortunately not sufficient reason to push back.

Now, Carpe Glitter is a novelette. Was it published as a standalone originally, or did it appear somewhere else or…?

It was a standalone. Meerkat Press came to me and asked if I had any novelettes or novellas because they were starting a standalone series. And I think it had been to a couple of markets. And it actually was sort of sitting on my shelf because, as you know, longer stories are harder to sell. And so, I gave it to them, and I was so happy to work with them. And then it surprised me by winning a Nebula Award, which was super cool.

Yeah. What was that like?

That was a ton of fun. I’m kind of sad that I didn’t get to go to the Nebulas in person, but they did just a glorious job with the online events. And honestly, I had talked myself out of it by the time that they announced it, you knew, as you do, you’re just like,” I’m not going to be disappointed. I know I haven’t won.” And so, when I won, it was just…really, it was very cool.

You’d been nominated before. But that was the first time you’d won.

That was the first time I’d won. And I’d…actually I had been nominated once and stayed on the ballot, and then I had been nominated once and there was an unfortunate issue with it having been put in the wrong category. And I ended up withdrawing from the ballot that year because if I had moved categories, I would have bumped three people off of the other ballot because they were tied and I didn’t want to do that.

You’ve been nominated for a World Fantasy Award, too. Do you think awards are valuable?

Oh…no.

I mean, aside from the, “It’s really nice to win one because it makes you feel good.”

Well…I do know that…I think it increases your stock a little bit. I know that I’ve talked to Ann Leckie, who was a classmate at Clarion West and sort of irritated us all by winning, like, every single award that she could the first year she published a novel, and she said, yeah, it’s made a difference to her career. Because she won the Hugo, she won a Nebula, she won a, I forget…Compton Crook, and she won a Clarke Award. She’s just disgusting. And I love Ann, but if I didn’t, I would have to kill her because she’s just way too talented.

Yeah. I mean, the one I’ve won is the Aurora Award here in Canada. Won it for this podcast, actually the first time I won it for a novel, but then I won it the podcast last year. And it’s really nice, and it gives you something. But, especially in the case of the Aurora, which…this is a pretty small market up here…I can’t say I’ve noticed any uptick in sales or anything. But every time a book comes out, they’ll put…you know, you can legally…not legally, but morally, say, award-winning author. So it does that.

Yeah. And you get an award. Like, I have my Nebula sitting on my shelf. I can look at it, and it’s really pretty. And it reminds me that people read my books and like them. Because writing is so solitary, as you know, it’s nice to be reminded that it’s not entirely.

That’s kind of the big philosophical question which I was headed to, which is, why do it, then? Why do you write, and why do you think any of us write, and why write this kind of stuff in particular?

Well, I think to a certain extent…at least, I meet a lot of writers who, like myself, we write because we kind of have to. We are always making stories. We are watching a paper cup floating down in the gutter, kind of going along the street, and we’re constructing a narrative in our head where it’s the brave little paper cup, and it’s, you know, that sort of thing. I mean, we just, we make stories all the time, and we like making them because making art is pleasurable. Making art is very pleasurable when other people like it, it builds to our ego. But making art is simply pleasurable for the sake of making art and knowing that you created something cool that nobody else could create.

Well, I think most writers would…or have, actually, at least for part of their career, wrote without any particular expectation that anybody much was going to, you know…it wasn’t going to get published. And even if you weren’t getting published, would you still write?

Oh, yeah. Yeah, definitely.

Now, I want to go back to the teaching of writing. I have to ask you about the Rambo Academy for Wayward Writers. Where did it come from, and how did it get the name?

So, I was teaching for Bellevue College, and no offense to any Bellevue College people that are listening, but I looked at my paycheck, and then I looked at the brochure and noticed the amount that they were paying me versus the amount that they were charging the students. And I thought, well, that seems like…kind of like a big discrepancy, actually, because I was making, like, twenty-five bucks an hour. And Google Hangouts had just come out, and I was, I had a lot of people who were also coming up to me at conventions and saying, “I really want to take a class with you, but you’re not in my area. How do you do it?” And so, I started teaching classes online about ten, eleven years ago. And at some point, I talked to my friend Rachel Swirsky and said, “You’re interested in teaching, will you come talk to my students about a class?” And then, I forget…Ann Leckie, actually, I think was the second person I brought in, I said, “Ann, will you come talk to them about space opera?” And after that, I started going after people that I wanted to take classes from. And we now have on-demand and live classes. We have a virtual campus, which, during the pandemic, we actually have been doing daily coworking sessions, and we have a short-story discussion group, and the people play writing games for an hour every week. So, the school has become a very important part of my life, actually. Particularly nowadays, that virtual campus is a place that I’m hanging out. Yeah, it’s my community.

How did you get started teaching to begin with? What drew you to, from just writing to start trying to teach other people how to write?

That was how…for Hopkins, for grad school, I got a teaching assistantship. And they had us teaching absolutely hapless Johns Hopkins freshman creative writing. Talk about the blind leading the blind. And it was this class called Introduction to Contemporary American Letters, which was basically, in my opinion, a scam to sell books by the faculty members. And so basically, they were like, here’s a list of twelve books, it just happened to be twelve books of fiction by our faculty members that you will teach. And so, it was always a very eclectic and kind of weird mix of fiction and poetry. But you have not lived until you have tried to explain John Barth to freshmen that are actively hostile to the idea that fiction might actually have something more than just sort of a story in it. It’s just…it was hysterical and wonderful.

But clearly, you got the bug.

I did. I like doing it. I like teaching. I like explaining things. I don’t even know…I like talking to people. And I think I’ve always been one of those people who enjoys talking to people and giving them advice. I suspect, were I not a writer, I would be a counselor of some kind.

Well, and is that side of things kind of what led you into becoming so involved with SFWA?

A long time ago, when I was up at DragonCon, I took one of my first writing workshops with Ann Crispin, who was a long-time super volunteer. This would have been in 2004. And she said to us, “You write a story and you qualify for membership. You join SFWA and you volunteer. And that is what you do. That is the career path you will all take.” And I was like, “Yes, ma’am.” And so, I qualified and joined. I was on a committee actually with Cory Doctorow on copyright. So, that was interesting. So, yes, that was one of my first experiences.

And then you rose up through the ranks…

Rose up…

And is it as much like herding cats as has sometimes been said?

Oh, God. It’s hysterical. Because you’ve got…like, there’s two thousand members and they are all strong, most of them are what I would call strong personalities, and even the ones that are very shy are very capable of being very strong personalities online, and you have a lot of ego, and writers are by nature insecure and prone to imagining things, which is not a good quality in a membership, in my opinion, but I mean, I had so much fun with SFWA. I made so many good friends, and one of the things that I did when I was done that last month was I sat down and I wrote a thank you note, and wrote them to all the people who had helped me or who I had encountered. And I’m sure I left out a bunch of them, but I sent out over 800 thank you notes to people.

Did you get any sense of the…state of the union, I guess, state of the genre, from your time there? You would have a different window on things than I think those of us who are just writing our stories and sending them to editors.

Oh, I think right now science fiction is in an absolutely marvelous time in some ways. I think that you’re seeing a lot of potential with independent publishing. You’ve seen a lot of potential with stuff like games that are also fiction. One of the things SFWA has done is that they now have a game writing award, which includes interactive novels and stuff like that. And it’s also a time when people, many people are working to bring a more diverse group into publishing and trying to help the already diverse folks that are there, and to me, I see a community that is so well-meaning and so good about helping each other that it is, quite frankly, one of the things that still gives me faith in humanity in, as we said, today’s odd world.

Well, I guess we can wrap things up here pretty much. First of all, though, what are you working on now?

I am writing a book two in a space opera series, the first of which is coming out from Tor Macmillan next March.

And what’s it called?

It is called You Sexy Thing, which is the name of the intelligent bioship that my protagonists steal.

So, it sounds like a far-future space opera.

It is. It’s a bunch of retired mercenaries who have started a restaurant aboard a space station. And then a mysterious package arrives, things start exploding, and we are off on adventure.

And anything else that’s in the offing?

I have a fantasy novel that should be coming out soon. It is the third book of the Tabat series, Exiles of Tabet, and I’m finishing up the edits on that right now.

And where can people find you online?

You can always find me on Twitter as @CatRambo. Most social media I’m there as Cat Rambo or findable thereon, or find me at catrambo.com.

OK! Well, I think that kind of wraps up everything I have to ask. So, thanks so much for being on The Worldshapers. I enjoyed it. I hope you did, too.

I did. Thank you very much for having me. I appreciate it.