Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

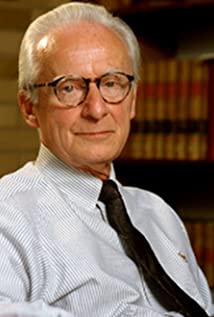

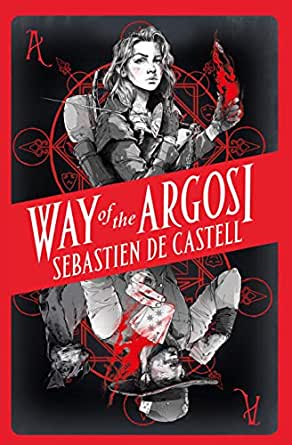

An hour-long conversation with Sebastien de Castell, award-nominated author of the swashbuckling fantasy series The Greatcoats and YA fantasy series Spellslinger, whose latest book is Way of the Argosi.

Website

www.decastell.com

Twitter

@decastell

Facebook

@decastell

Sebastien de Castell’s Amazon Page

The Introduction

Sebastien de Castell had just finished a degree in Archaeology when he started work on his first dig. Four hours later he realized how much he actually hated archaeology and left to pursue a very focused career as a musician, ombudsman, interaction designer, fight choreographer, teacher, project manager, actor, and product strategist. His only defence against the charge of unbridled dilettantism is that he genuinely likes doing these things and that, in one way or another, each of these fields plays a role in his writing. He sternly resists the accusation of being a Renaissance Man in the hopes that more people will label him that way.

Sebastien’s acclaimed swashbuckling fantasy series, The Greatcoats, was shortlisted for both the 2014 Goodreads Choice Award for Best Fantasy, the Gemmell Morningstar Award for Best Debut, the Prix Imaginales for Best Foreign Work, and the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer. His YA fantasy series, Spellslinger, was nominated for the Carnegie Medal and is published in more than a dozen languages.

Sebastien lives in Vancouver, Canada with his lovely wife and two belligerent cats.

The (Lightly Edited) Transcript

So, Sebastien, welcome to The Worldshapers.

Thanks so much for having me.

I should have practiced “dilettantism” before I tried to read that bio.

Yeah, that’s that’s one of those tricky words, isn’t it, where there’s just one too many syllables for what we kind of expect when our eyes go over the word

And all those Ts. It’s very confusing. But yeah. So, we are both in Canada, we haven’t met anywhere, but we do share a publicist in Mickey Mickkelsen from Creative Edge, and that’s kind of how I made connections with you. Also, you were mentioned by Chris Humphreys, whom I interviewed not that long ago, as somebody who was kind of a beta reader for his stuff. And I thought, hey, I should talk to Sebastien. So here we are.

Well, you know, I’ve only recently met Mickey and he seems lovely, but I think it’s important to get on the record that Chris Humphreys is a dastardly rogue. He’s too talented. He’s too good looking. And above all else, he’s far too British for anyone to trust.

Well, I enjoyed talking to him anyway, and I’m sure I’ll enjoy talking to you, too, as well. So, I’m going to start as I always start, which is to take my guests back into the mists of time—I’m going to put reverb on that any day now—and find out . . . well, you started in archaeology, you didn’t start in writing, but you must have been interested in reading and writing before that. So how did that all come together for you? How did you get interested in in the world of telling stories, and where did you grow up, that kind of thing?

Oh, all the all the good stuff. I grew up as a young man in a troubled small town far to the east where . . . no, I was never one of those what I think of, and perhaps inappropriately, as natural writers. I’m not sure there is such a thing as a natural writer now. But I often meet other writers who will talk about the fact that they were always writing, and I was not always writing. My first serious foray into writing was when I was 27. I was in a a beleaguered and failing rock and roll band making, you know, two hundred and fifty bucks a weekend playing cover tunes, being sued by the bass player for control of the band. And when you’re being sued over control of a of a group who fundamentally makes their living playing “Brown-Eyed Girl” in bars in the interior of British Columbia, you know, you’ve hit a creative low point in your life.

And so I did what I did, what I think I’ve always sort of done in my life when I felt like I was, you know, missing purpose and a plan, which is I went to the library. And, you know, like most writers, I’m a huge . . . not so much an advocate of libraries, but a huge user of libraries, someone whose entire existence to some degree relies on the fact that libraries are there and that at any point in your life, no matter what’s going on, no matter how confused or depressed you might be, you can walk into a library and all of a sudden there’s, you know, a million different possibilities to sort of explore.

And when I was there, I found a box of book tapes, which was a course by a guy named Ralph McInerny, and it was called Let’s Write a Mystery. And this was such a strange thing. It was a set of 24 tapes. Twelve tapes, 24 sides, cassette tapes, and an accompanying book, and the accompanying book was the draft of a novel that he writes as he’s dictating these tapes to you. And he talked in a sort of a 1960s professorial sort of voice, the kind you would have heard in science class in high school, where you would sort of say, you know, “And today we’re going to make our protagonist and he should be a guy you’d like to have a beer with.” And oddly, that kind of strange, soothing tone allowed me to do something I don’t think I’d ever been able to do before, ever would be able to do before, which is to write my way through a novel for the first time. And as it should be, as the universe demands, that novel was terrible. It’s called Skeletons in the Cloister. It’s an archaeological mystery that deeply reflects my love of archaeology, or lack thereof. But it taught me everything, you know, it suddenly changed the entire way that my mind worked, such that I was able to conceive of how to write a novel, like, nothing felt too big anymore.

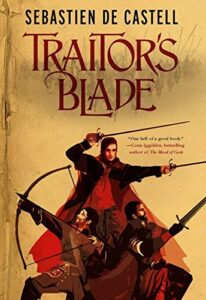

And so, a few years after that. . . and I felt so good, like, it just changed my life in the sense that even having written this one terrible novel, I was just so much more confident and so much more interested in people and in the world around me. And a few years later, I decided to do what’s called the Three-Day Novel-Writing contest, which is an annual contest that’s been around forever, where you try and write, you know, something in three days. And I ended up writing 44,000 words of a novel in three days. All the while, I think I still went for runs. I slept more hours than I usually sleep. And I had a music gig where I had to learn to sing “The Lady in Red,” which is a rather painful song for me to sing for purely musical reasons. And so, somehow I ended up with this draft, which I was super happy with. And years later I decided, What the hell, I’ll give a shot at this. And I revised that novel and nearly tripled the length in the process. And that became Traitor’s Blade, which was the first book in the Greatcoats series, which launched my career. And, you know, it has gotten me to the lofty heights to which I ascend to this day.

Well, if we go back, way back, you must have been a reader. Nobody suddenly decides to write if they haven’t been a reader. What sorts of things did you read growing up?

Well, when I was . . .I came to reading actually through my sister, who when . . .I was a comic- book reader as a little kid. In fact, the first time I realized I could read in English was reading a comic, because I used to just look at the pictures. And then I went to French school, even though I only spoke English. Getting dumped into French school at six years of age when you only speak English is quite a trauma, I can tell you. And so, my first sort of actual exposure to learning to write any language was in French. And then one day, I suddenly noticed I could . . . I was looking at the same old comic books and realized I could read the words, which was a very strange experience to have. But from there, I sort of, you know . . . when I was about nine years old, my father was dying of cancer. And my mother asked my sister, who is about 15 years older than me, to take my brother and I on a trip to England and France to kind of get us out of the house, I guess. And I mean, we didn’t have much money. So, you know, how my mother and sister made that work is still baffling to this day. And she started reading to my brother and I from The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. And so, I became completely enthralled with Narnia and in that world for a while.

But it wasn’t until in my teens where I really started reading in English for myself. I read when I was in French school, I wasn’t always . . . I had a period of time where—I think lots of us do—where you get kind of disconnected from other people. And again, the library, the school library, was a sort of a place of refuge. And I read a little bit there, but it was when I was around 15, 16, where a friend of mine in an English high school by the name of Edward Swatchek (sp?) was kind enough to give me a copy of a book called Jhereg by Steven Brust. And I was just blown away by this book. I mean, I still think in many ways he’s not recognized—even though he’s widely admired. I don’t know if he’s recognized to the degree to which I think he helped inform some of the stylistic options available to fantasy writers, that we didn’t have to write everything in “thees” and “thous” and things like that.

I certainly remember my encounter with him when I was probably university age, when I ran into Steven Brust and I read everything I could get my hands on.

Yeah, me too. You know, To Reign in Hell is, like, such a deeply troubling book, actually, that I . . . I adored it but could never read it other than the one time, because there’s just so much for me. There was just so much emotional trauma tied to how well that story is told. But I so I kind of fell in love with that. And that kind of led me to other books, some of which are sort of forgotten sometimes, including Keith Taylor the wonderful Australian author’s Bard books about Felimid mac Fal He wrote a series of books about an Irish bard that were just so full of sort of verve and zest that they made me want to become a bard, which to one degree or another, for the rest of my life, I’ve been sort of trying to do that, which is partly how I got stuck being sued by the bass player . . .

I was going to say . . .

The bass player is a perfectly nice guy, by the way. We’re still friends. And, you know, and into some books that I think are now being sort of reconsidered to some degree, like Stephen R. Donaldson’s Thomas Covenant books and things like that. So, my sort of, you know . . . which is, sorry, a very long-winded way of saying, like my sort of sense of fantasy, which is the domain in which I largely write—I also write sort of mysteries on the side, but not that I think anyone would really want to read—but my sort of sense of fantasy was really drawn from the ‘80s, which is a strange place to derive it from because it’s both too late to be the classics and sort of too out of date to entirely sit within the, kind of the present taste for fantasy.

Well, what actually then drew you into archaeology that you then found out you hated when you actually had to go on a dig?

At the time, I would have had a better answer. Positioned as I am sufficiently far away from it. I think it’s I can admit that it was Indiana Jones.

Mm hmm.

And the thought of adventure. You know, adventure is a very difficult thing to get these days. Right. You know, society isn’t really structured around adventure. The kinds of adventure that are largely available to us as human beings now involve either extreme sports, which, you know, doesn’t sort of have that kind of quest feeling to it unless you really like hiking up dangerous mountains, which is great, but not totally my thing. Or if people, you know, sort of want to join the military, which requires, you know, a sort of an ideology that not everyone necessarily shares. But there’s not all the sort of opportunities for adventure and archaeology. When I was in university, you know, I think, as many people did, I conflated it with the sort of adventurous side that’s presented in an Indiana Jones movie—which in my defense, because I realize this sounds pretty pathetic, but in my defense, the archaeology department at Simon Fraser University did once confirm to me that every time a new Indiana Jones movie came out, their enrollment shot up through the roof.

I’m pretty sure Indiana Jones’s approach to research and working in the field would not work in the real world.

But what’s absolutely fascinating about that to me now is, because I remember by the time the second or third movie was coming out, people were sort of saying, “Well, you know, that’s not proper archaeology.” And, you know, we now know that it’s not. But if you listen to or read the transcripts of the original conversations between George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and I think Larry Kasdan, who actually wrote the script, they were very intentional about the fact that this was not a good-guy archeologist. He wasn’t doing archaeology. He was a kind of antiquarian thief. And that his sort of justification was, someone’s going to raid these temples anyway, someone’s going to steal this stuff. At least if I steal it, I’ll sell it to a museum rather than a collector. And so, there was a . . . there’s a stronger element of the anti-hero in Indiana Jones than there is in Han Solo, who is regrettably often quoted or listed as being an anti-hero, when, in fact, he’s nothing of the sort.

The archaeology thing and being on a dig and realizing you didn’t like it . . . I went through the phase like many kids do, thinking I might want to be a paleontologist because, you know, dinosaurs are cool. And then I’ve had the opportunity since then to be really into paleontology digs and all that bending over in the hot sun with a toothbrush, brushing away dirt, I realized . . . much as when I went out with a veterinarian, a farm-animal veterinarian, and had to see what they did with farm animals when I was in high school and I realized that veterinary medicine was not for me either.

Yeah. My goodness. You know, paleontology is archaeology magnified in the sense that . . . I often tell people that archaeology is an excellent—like, field archaeology specifically because obviously there’s many, many different kinds of many different branches of archaeology—is actually, by the way, a good career. People do earn good livings as archaeologists, strangely enough. But field archaeology is an excellent endeavor if you really like camping, because basically that’s what you’re doing. You’re camping and then you’re out in the hot sun and then you’re pulling out the toothbrush. And, you know, at night there’s the campfire and drinking and not tons of showers. And, you know, if that’s your thing, it’s fantastic. I’m really . . . probably no one’s going to quote me when they’re putting together posters to promote archaeology programs. But it is it is a wonderful field. I’m super glad that it exists. And I’m almost equally glad that I’m not in it anymore.

Well, the drinking and camps . . .we’re not far from here is the Royal Saskatchewan Museum, and it has a cast of Scotty, who’s the largest T-Rex found in North America. And I was at the dig when they were pulling him out of the ground out in the Frenchman River Valley. But the reason he’s called Scotty is because when they found him and realized what they had, they went back to camp and drank a bottle of scotch. That’s why he’s Scotty. And the paleontologist, Tim Tokaryk, who was working on it, said that it’s like when you have a find like that, it’s, “Yeah, this is exciting.” And then, “Well, now I know what I’m working on for the next multiple years of my career.” I also wanted to ask you about being a fight choreographer. You actually are somebody who knows how to use a sword, is that right?

I am, in as much as anyone sort of knows how to use a sword without ever having to actually risk their lives with one, because obviously that changes everything. But yeah, I used to fence quite a bit. Years and years ago. And then for a while I was doing sword choreography for the theater and that, you know, informed my writing in all the ways you can imagine. But so, there are other . . . there are many other writers in fantasy who have far better credentials on that particular front than I do. I think specifically of someone like Miles Cameron, who is genuinely a historian, both more broadly and specifically of arms and armor and things like that. But, you know, I have some game

And you’ve done some acting as well. And I always ask about that because I’m a stage actor and I have found that being an actor influences my writing as well in a beneficial way. So ,I’m just curious, all these things, the archaeology, the fight choreography, the the acting, the music, does that all fit into your stories, do you think?

Oh, absolutely. I think one of the beautiful things about writing, and something I’m very passionate about, just as a human being, is everyone writing a novel. I think everyone who wants to write a novel should write a novel. I think we all have a good book in us. It’s just varying levels of effort to get it out. And often, I meet people who are nervous about . . . they’re having trouble writing their novel and they get very stressed out and they’re worried that because they’re having trouble, they won’t do it. And I always say that one of the wonderful things about writing, and I think especially fiction, is that it feeds on everything you’ve experienced. And so, there’s always time to write your novel in the sense that, you know, if this isn’t the year, it might be next year or the year after. It might be that it’s the experience of going to a place or doing a particular job that’s going to unlock it for you. And all of it feeds into it.

For me, music is probably the element that influences my writing more than anything else, because music introduces that notion of the contrast between rhythm and melody and rhythm can very loosely be attached to pacing, for example, inside of a scene or inside of dialogue, and melody can kind of loosely be attached to the sort of emotional intensity and tonality of the writing. So ,everything influences it. But I’m often more conscious, I would say, of music as driving the feeling of a scene for me as I’m writing it. And, you know, very frequently when I go . . . I run quite a bit. I’m an absolutely terrible runner, but running has this weirdly perfect combination for me that . . . it’s hard on me because I’m not good at it, and so it makes me emotionally kind of vulnerable. And so, I’ll listen to music, which also tends to make me emotionally vulnerable, and I will have to conjure up scenes, and then I’ll have these profound emotional reactions to an idea for a scene. And so, people will be wondering why this pathetically slow runner going up a hill is crying.

I would cry running up a hill, but . . .

It’s just that thing that allows you to kind of, you know, put things together at that right moment. That’s so much . . . I think what the act of creation is from the standpoint of a novelist is, it’s this combination of you have to put your body and your brain into a particular state. For some people, that’s, you know, they burn incense and light a . . . and drink the right tea and sit at the right place at the right time of day. For me, it’s actually being somewhere. It’s doing something. It’s having an experience that’s outside of my normal day that that kind of drives it. So then, it’s that putting yourself in that state and then allowing those kind of emotions to run a little bit rampant and all your dark little secrets to kind of creep up from your subconscious. So, yeah, so all those sort of activities help, but they all help in different ways. You know, the fight choreography taught me a lot about the role of a character inside of a scene because, you know, you were mentioning . . .. you’ve been a theater actor, have you done any stage fighting?

Not with weapons. There’s been a couple of fistfight things, but that’s all.

Well, you know that typically . . . you know, there’s a famous sort of Shakespeare line, “They fight,” which is . . . you’ll have this massive script full of the world’s most amazing dialogue. And then it’ll be, you know, somewhere it’ll say Romeo and Paris confront each other in the fourth act or third act of Romeo and Juliet. And they have these lines, wonderful lines of dialogue. And then it just says, “They fight.” And so, what a fight choreographer has to do is somehow put in a piece o choreography in which that conversation continues, but without words. And so, the way a character fights . . .and then, this, I think, can be expanded to the way a character moves and can be expanded to the way a character does anything is a constant reflection of the sort of the narrative that they’re telling about themselves, right? I am the hero in this fight. And, you know, I’m much more devious than you think I am. You know, all of these sorts of things can play out inside of a swordfight, which is what makes those fun for me to write

I’m not someone who typically watches or aims to watch, you know, boatloads of action movies because often those are spectacle devoid of narrative. Not always. You know, if you watch . . . I think Jackie Chan is particularly wonderful at this putting kind of a story into his fight scenes. But a lot of fight scenes now tend to be spectacle without the need for narrative. But so, that’s what I learned from fight choreography. So, to round it out, all of that kind of informs the writing and sometimes in ways that you’re conscious of and sometimes in ways that you’re not.

Well, I think for me, it’s not the fight choreography so much, but just the acting and the fact that when you’re acting . . . I’ve also directed plays, and you’re always extremely conscious of where everybody is in relationship to each other within the space. And I think that that carries over when it comes to writing scenes and having that mental image of where everybody is in relation to each other. And when I mentor younger writers or do instruction, I will sometimes find scenes that seem to happen in just kind of this amorphous grey space and there’s no sense of place and they lose track of where characters are. And I just think that the acting and directing side is kind of helps with that and obviously fight choreography even more so when it comes to writing those fight scenes.

I just wanted to say, I think I always view the actor role slightly differently in this regard, that . . . the thing I didn’t understand about acting, even probably in the time when I was an actor properly, is that an actor’s job isn’t to perform a particular set, deliver a particular set, of words while making a particular set of actions, but that it’s a much more sophisticated process in that they’re creating all of these interpretations and layers that aren’t available in the script itself. And for me, that’s what the reader does, right, that when the reader picks up the book, they’re reading the script and they’re having to direct all of the action and produce all of those, a lot of those layers of subtext themselves, which is what’s so amazing about it. It’s also one of the reasons why I absolutely adore getting, hearing, the audio books of some of my books, because there you have an actor and often an extremely skilled actor who is suddenly taking your text and adding all of these layers to it that are, that just for me, just bring the story alive in a completely different way than I expected.

Yeah. I often say that although writing is a solitary act, it’s actually a collaborative art form and that you’re collaborating with the reader and you don’t actually know what the final art form is because it happens individually in each reader’s head. Each reader is constructing their own version of your story based on their own background and understanding of the words that you were using. And it’s really, really fascinating to think about that. When you write a book, you’re actually writing a whole bunch of books, because every reader is getting a different book out of it.

Absolutely, and yeah, and I’m philosophically I’m a believer in reader response theory, which argues that the only, that the true narrative act is, is when the reader reads the text, that s the author, our, you know, our intent becomes irrelevant the moment the words are fixed to the page because it doesn’t matter what I intended or what I was thinking. That’s not available to the reader. There’s only the text and they will, from that text, conjure up whatever they want to conjure.

It’s one of the reasons I also don’t take it too personally if sometimes someone will say, you know, “Oh, this this represents this, this scene represents something horrible or this character is vile,” or, you know, this book is about something that it’s not about for me because I always recognize well, it is about those things for that reader. And it’s why I think, you know, literary criticism is such a tricky area. You know, it’s expanded so much because, you know, everyone has a YouTube channel now or lots of book bloggers are out there. And there’s sometimes a sort of an attempt to kind of consolidate a sort of a definitive interpretation of a book, which to me is a pretty problematic effort at best. Whereas, you know, sometimes when people are just trying to share what they love or even what they hate about a book, that sort of to me always feels like a more personal expression. And therefore, it always aligns better with my own sense of, as I say, a reader response theory, that every reader is the one constructing the story from the text.

That’s interesting. I’m currently reading a collection of Robertson Davies essays published just after he died in the mid 90s, and he had a line in there to the effect that he hated it when a reader would say to him, “So what you’re trying to say in this is,” and he would always say, “No. I said what I’m saying to the, you know, to the best of my ability, your job is to figure out what I’m saying.” And I thought, I don’t quite buy that.

You know, that always feels like a very Canadian thing to me. I don’t know why, but I always feel like, when I hear kind of the Canadian literati talk about books, that there’s such a strong adherence to a very old-fashioned notion of literature as this thing created by great minds that the rest of us should struggle to interpret. And if you don’t enjoy a great book, it’s because you didn’t interpret it correctly. And if you didn’t get out of it what the author later informs you through their memoirs they intended, then it’s because, you know, you didn’t interpret it correctly. So, I’m not a big fan of that perspective, I would say, which is nice, because this is my first time explicitly contradicting Robertson Davis. I’m sure that will go down in the annals of literary history.

I mean, I loved his essays. I love reading good stuff, but I did kind of push back against that. Well, now let’s move on to your process for creating great literature. But you have a book that’s just coming out, Way of the Argosi. When does that come out?

That comes out on April 19th. It’s oming out in various languages in various parts of the world, but I’m not actually sure what it’s publish date for North America is going to be. So, it’ll be available in pretty much everywhere except Canada and the United States on April 19th. It may end up being available in Canada and the United States on that date. But it’s a little wishy-washy right now.

Well, this this, as it happens, unusually for these podcasts, we’re doing this just a few days before it comes out. We’re doing this interview on a Monday, or is it Tuesday? And it will be coming out this coming weekend. So, it’ll be out very, very promptly, so, before that comes out. So, let’s start by a synopsis of it, and then we’ll talk about how you created it as an example of your creative process.

Sure. So, Way of the Argosi is a young adult fantasy novel about a young refugee who is pursued and tormented by the mages who massacred her clan. And as she sort of struggles to survive in this world, she finds herself trying to adopt the kind of archetypes of different ways that people navigate the world ,of trying to behave like a knight and, you know, trying to, you know, value honor. And when that sort of fails for her, trying to be a thief and surviving that way, but then finding the limits of that, and ultimately coming to meet one of these rather strange and enigmatic kind of what I would call a cowboy gambler, monks who are called the Argosi, who sort of offer her a somewhat different path through the world. But it’s one that comes at great cost. And so, that’s what Way of the Argosi is about. It’s the . . . the main character is Ferius Parfax, who is a character who appears prominently in the Spellslinger series. But this is her story, told for the first time.

Well, I haven’t had a chance to read the entire thing, but it immediately gripped me with the opening scene with the 11-year-old girl hiding among the corpses, you know, going on from there. Very gripping reading and opening, I think. Greatcoats, your first one that made your career, as you said, that wasn’t YA, was it?

No, no. The Greatcoats is definitely adult fantasy. Although, you know, the dividing line between adult fantasy and young adult fantasy is blurry at best. It’s very much a sort of a marketing distinction at times. If you think to the classic fantasy that we probably read as kids at various points, it very often featured younger characters who might start, you know, Way of the Argosi only briefly has Ferius as sort of 11, and then it progresses into her teenage years. But lots and lots of, you know, the Belgariad by David Eddings, for example, I think the main character starts out very young and stays very young throughout pretty much the whole series. So, it’s an odd distinction. But The Greatcoats definitely sort of fits into that classification of adult fantasy, if only because it sort of features a trio of middl-eaged men.

So why did you start focusing on YA? Because your next series was YA, was it not?

That’s right. Spellslinger sort of fit into that Y.A. category. I think . . . my wife is a librarian and she, I think, gave me the best definition of her notion of YA at one point, which was that young adult stories are about first experiences. And so, what happened was . . . Spellslinger was kind of interesting. Originally ,I was going to write it with one of my best friends and I sometimes write with a guy by the name of Eric Torin (sp?), who’s a well-regarded video game person, but also a terrific writer. And we wanted to write something together and we were spit-balling various ideas. And then. his life got very busy and he said, “No, you go off and do it.” And so, I’d written this story about an exiled former mage, you know, wandering the desert like Kwai Chang Caine from Kung Fu, which is a reference not everyone will get.

I do!

Yeah. And, you know, a more modern parallel is probably Jack Reacher in the sense that Jack Reacher is sort of like, you know, David Carradine in Kung Fu, but without the philosophy quite as much. And so, I had written this book and I I loved it and my agent loved it. And then it went through this sort of odd cycle of things where, all of a sudden, I was being asked by various publishers who are sort of saying,”Look, we would love to see a YA trilogy of prequels to this and would you be interested in doing that? And could you write a rough outline of what that would look like?” And I said, “OK,” which is always the first mistake I make when I’m asked to write a book proposal because they’re nightmarish, not so much in the process of making them, but in in the consequences where now you’ve basically given somebody nothing they can fall in love with, but something that they can critique.

And so, it kind of went through various cycles of that, where they say, “Well, now we need some chapters. Well, now we need some more chapters. Oh, this is looking really good. Can you write even more?” And I was like, I said, “You know, I’ve written almost half the novel now. I think you’re just asking me to write the novel.” But eventually, it sort of went back and forth between a couple of publishers. And I ended up with this very strange eight-book deal from Bonnier in the U.K. for world rights. And it was a really great deal. It basically meant for four years of my life, I had, you know, a ful-time, excellent income just writing those books. And so, we originally said we would do four books, would be Kellen as a young man, and four books would be Kellen as an adult. But then then an editor came on board who said, “Well, actually, I think we’d like six books, all telling the story of his youth,” which is what we did.

And then, that left two books on this contract. And I said at one point, “You know, what is it you want me to do with these other two books?” And they sort of said, “Well, you know, write whatever you want.” And I thought, Well, that’s like a really strange thing to do. And I didn’t have high hopes that doing so would result in a massive marketing push. But I was really delighted working with Bonnier and their imprint, HotKey Books. And so, as we were coming around the bend of wrapping up the six-book series about Kellie, I said, ”Look, you know, I’m if you want two more spells on your books, I’ll write two more Spellslinger books. If you want something different, I will, like, let’s talk about something that you could be passionate about.” And they were kind of interested in something that was set in that world but wasn’t just a continuation. And in the meantime, I was getting these letters. I get quite a bit of fan mail, or more than I sort of expected to get as a writer. And often the fanmail I get is from people who will say, “I read Spellslinger, I want to become an Argosi, tell me how to become at heart Argosi. And of course, you know, it’s a strange thing to try to sort of helpfully answer those letters because I am not an Argosi and there is no, you know, there’s no school of the Argosi.

But what I think people were sort of falling in love with was this notion of this system . . . the Argosi are a little bit like the Jedi, except rather than having basically magic, they kind of don’t revere magic, but they sort of mock magic. You know, in fantasy novels, magic is always this sort of moral superiority in a sense. You know, we all want to have it. And the Agosta are sort of like, “You know, that stuff’s all kind of children’s games. The real thing you need to learn how to do is dancing, you know, or singing, or learning languages.” And so, what the Argosi do is, they take very human phenomenon and, like, very human things, and they kind of elevate them almost to the level of magic. And the best example I can give is sort of martial arts, right? When you think of it, martial arts are pretty amazing, right? Like, the human body is a pretty crappy instrument for most forms of violence. We don’t have very good, you know, biting teeth. We don’t have very good claws. We’re sort of gangly-limbed. And somehow, humanity over the millennia has sort of created martial arts where all of a sudden these otherwise gangly bodies can become kind of amazing inwhat they can do. And so, I was sort of extending that with language and wit and even with something like swagger, like charisma and confidence.

And so, that’s what the Argosi kind of do. And so I . . . and because the Argosi are also an expression of my own philosophical bent towards existentialism, which, you know, of course, as with everything else, I’m not an expert on. But for anyone who’s completely confounded by what existentialism is supposed to mean, in its simplest form, it’s the idea that there’s no inherent meaning in the universe. There’s no natural purpose to anything. But humans, for whatever reason, can’t seem to live without a sense of meaning. And so, you know, existentialism is a philosophy that says, therefore, what you have to do is decide what is meaningful to you and live authentically to that. And so, the Argosi, rather than being a kind of an order of knights, as we’ve seen in the past, that have, you know, you must be this, this and this, or unlike the Jedi, let’s say, from Star Wars, the Argosi believe that every person has to find their own path and sort of take that on and embrace that and follow it where it leads. And so that seems to be, I think, very appealing for a lot of people these days who don’t feel like a lot of the traditional avenues that that, you know, our parents had or their parents had fit them very well. And so I, when it was time to deal with these last two books, I said, “You know, maybe I’ll write something that’s . . .” My original idea was was I’m going to write my own version of Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist, which really nobody should do. I’m not entirely sure Coelho should have done it, because The Alchemist is basically sort of a fantasy story that is him expounding on his personal philosophy and spirituality.

And so, that’s why this got called Way of the Argosi, because I thought, Oh, I’ll just expound on all of that. But, of course, you know, it became just a very personal story of of this character, various power facts. And along the way, we sort of, you know, pick up some of those things. But it’s not a sort of a guide to how to become an Argosi in that sense. It’s a tale in which in which some of those ideas are explored. And so, yeah, I’ve been absolutely delighted with it.

I, funnily enough, I received the audiobook. They sent me the audiobook to get to listen to and the performer, Kristin Atherton, is so amazing. And, you know, going back to what we were saying about acting, she just brings that whole story to life in this whole new way. And it’s absolutely captivating for me because even though I wrote the words, you know, she takes them and she’s made them her words. And, you know, it’s like I’m getting to hear various effects for the first time.

Well, I think in all of that, we’ve kind of covered some of my usual questions about where the idea came from and the development of it. What’s your actual writing process look like? Are you an everyday writer, do you do it in long stretches or snatches around other things? Do you write with parchment and the quill pen under a tree? How does it work for you?

I write exclusively in blood. Not mine, you understand, other people’s, because I would get tired if it was my blood. I’d run out of energy. So, my process is a giant mess. And to kind of give you a sense of how big a mess it is, I’ll put it this way. In January of 2020, so, January of last year, I called my editor at HotKey Books and they were just transitioning from Felicity Johnston, who was wonderful, to go to a new fellow, Maurice Lyon, who is also wonderful. And I had this chat with her and I said, “Listen, I’ve been trying to write Way of the Argosi. It’s not working. It’s really not working. I need to push back publication by a year,” which is not a nice thing to do to your publishers. She, of course, was wonderful and said, “No problem. You know, I understand. Do you want me to read some of what you’ve written?” And I said, “OK, but it’s a disaster.” And then she took it and she shared it with Maurice. And a few weeks later, we had this conversation and they said, well, no, the stuff . . . they loved what was there, but it wasn’t quite hanging together. And in the course of a sort of a 20-minute phone call or 30-minute phone call, you know, a couple of ideas were bounced around. And Maurice said something like, “You know, I feel like you’re rushing from the moment of her trauma in that opening chapter to later events,” and that it would be OK to explore some of the stuff in between.

And that doesn’t sound like a particularly profound insight. But 60 days later, two months later, I was turning in the manuscript of Way of the Argosi, and virtually nothing changed from that manuscript to the one that is dropping in reader’s hands in the book on April 19. You know, it was copyedited by the fabulous Talia Baker, who transforms my occasionally clumsy sentences into something closer to sublime narrative. But the story was all there.

And so, my process is so messed up that I can get to a point of literally thinking there’s no hope for a book. And then, someone will say something that will seem very, very basic to anybody else. And yet, all of a sudden, that unlocks things in more sort of tactical terms or pragmatic terms, which was probably where you were headed with the question. But I’m fabulous for derailing questions. But on a tactical level, look, there’s things that I’m always very cautious when I’m asked this question. And the reason I’m cautious is because I know that a lot of listeners are either writers themselves or thinking about writing. And I’m always terrified of imparting something that will sound like the rules for a field that you and I both know really has no rules.

It’s kind of the point of this podcast, is that everybody does it different.

No, absolutely. And so, it’s one of those things where I always feel like I have to keep saying, “But of course, this may work differently.” And in my own life, in fact, I have probably done every different kind of writing, every different approach, all within the bounds of the 11 books I have published so far. So, with something like Way of the Argosi, the way that it finally came out was in part by saying, “All right, I am going to write this draft, knowing that the story may not go where I want it to go may not be anything of any value. And I’m just going to write every single day.” And that’s what I did. So, for 30 days straight, all I did was write this book and I didn’t worry about whether it was going somewhere logical or not. And then, somehow, it did. But I’ve done that again recently with a different book, and it’s gone straight to hell. I mean, it’s gone into a book that makes no sense, that has, you know, no artistic merits or values whatsoever. And so, it’s always all over the map. You know, with Knight’s Shadow, the second Greatcoats book, I think I wrote a 45-page outline, and to some extent, I followed that outline. So, I sort of use everything. And that’s the big challenge for me when I’m writing a book, you know, and I’m actually kind of glad that you’re making me talk about it here, because it sort of forces me to remind myself of this.

The biggest challenge when I set out to write a book is to figure out what is the process by which this particular book is going to come to life, because I don’t know what process that’s going to be. So, it might be, sit down and write a big outline. It might be, have no outline and just explore. And even beyond those very tactical concerns, there’s often a mental game involved, which I don’t know if you encounter this because, you know, in your writings, maybe . . . I’d be interested in hearing how you deal with this. But it seems sometimes as if we have to program our own brains or deceive our own brains or tell ourselves something . . . like, I’ll have to trick myself by saying, “All right, I’ve decided that this book isn’t going to be published and I’m just going to write, I’m going to write a book that’s going to, that’s basically intended to irritate fans of fantasy, you know, that all these people that talk about what fantasy is and what it should be and what tropes are allowed and not allowed, I’m just going to, you know . . .”, and somehow that’ll get me to a book that doesn’t offend people necessarily, but it seems to work, whereas other times I have to tell myself some other thing. And so that whole internal process, I think that’s why I’m so sensitive to not wanting to ever make any writer feel like they’re doing something wrong, because I just never know what the process is going to be.

I think my usual trick is just telling myself that I’ll get this mess out and once I get to the end, I go back and fix it. The first person I interviewed here, Robert Sawyer, and he got the term from Edo van Belkom, I think he said, he calls his first draft the vomit draft, because you just vomit it out and, you know, it makes a huge mess that you have to clean up, but you feel better so you could get on with the cleaning it up. My next book for DAW Books, The Tangled Stars, is this big, sprawling space opera that turned out to be humorous, which I didn’t really know going in, necessarily. And I’m struggling with it a bit. But that’s really what I’m telling myself, is, I’ve just got to get the words out there and then I’m going to I’ve got to fix all this stuff I know it’s horribly wrong with it right now, but not until I get to the end. That’s kind of the way I tell myself.

It’s interesting, because I sometimes correspond with Dean Wesley Smith, who, you know, is the writer of any number of Star Trek and Men in Black novels and Marvel comics, superhero novels and things like that, as well as all of his own series, the Poker Game Series and things like that. And he has a very specific philosophy about writing, which is, you write one draft, you turn off the internal critic entirely. You allow your brain to take the story wherever it’s going to go. You can cycle back while you’re writing as many times as you need to clean things up. But once you hit the end, that’s it. It’s over. It may get a sort of a typo-cleaning pass, but that’s it. And he’s very firm about this notion that you have to trust what you write and if you keep second-guessing what you write that that you’re basically training your creative brain not to trust itself, so it’s . . . and I’ve had a couple of books recently where following that is sort of process really worked for me. I’ve had others where it didn’t. But it is interesting that that even that notion of the first draft, is that the first draft, this getting stuff out of yourself so that you’re more analytical brain can fix it, or is that first draft the true and genuine expression of the story your artistic self wants to tell you, therefore you have an obligation to it? That’s the question.

I would say with my . . . OK, we’ll talk about me for a minute. I would say with my writing, with my first draft that it is, I don’t change huge, huge things in these. You know, I have things to fix. But the overall story, I don’t, like, switch scenes around or move chapters here and there or anything like that. Once I have that something to the end, that is the shape of the story for sure. So, I guess I’m following a little bit into his way of thinking about it. So, it does get worked out in my head as I’m going. It’s just that I know at times that I’ve got I’ve got to do some foreshadowing back there because I didn’t really set this up and that sort of technical stuff. But the overall shape of the story, if I do run into trouble, which I did on my last one, The Moonlit World, I got to the middle of the book, realized that I could no longer get to where I thought I was going because my brain had changed things, and I had to go back and sort of take a fresh run at it from the beginning and read through it all and change a couple of things. And then, when I hit that stop spot in the middle, I was able to power through it and carry on to the end. So, it’s not . . . as you said and as this whole podcast is about, there’s no one way to do it.

And I think, yeah, it’s interesting, because I think the middle is the true book in a way, the true book that has to be followed in the strange sense that, you know, I will very frequently write an opening to a book that I think is terrific. And n fact, I almost never struggle to write a strong opening to a novel. But once you get into that second act, you know, however, one defines the second act, that’s where things get really, really fuzzy. And that’s where one of two things will happen, either for me, either I get lucky and I’m on the right track and that middle will carry me through that, you know, will carry me all the way through to the story itself, or I won’t be. And sometimes, I’ll do sort of what you described, which is I’ll cycle back to the beginning of the book, you know, right back, and all I’ll be doing is just changing a word here or there. It’s more just me reimmersing myself in where I started from and see if I can get to a better launching point in that second act.

The thing that appeals to me, I have to say, about Dean Wesley Smith’s model is the notion is it allows for the notion of a novel from the standpoint of a writer being a journey that you begin with the first word on the page and end with the last word at the end of the book. And that’s just, psychologically, for me is so appealing, right? The notion that today I will sit down and begin a book and then, you know, X number of days from now, I will end that book and it will be finished, I will have completed that journey, I will have climbed the mountain as opposed to what very frequently happens to me. And by the way, part of what informs this is, I am not kidding, I’ve turned in the tenth draft of Play of Shadows, which is the first book in the new Greatcoats series, the tenth draft. I’ve never done 10 drafts a book and that starts to feel like you go and you climb this mountain and you get to the top and discover that you took the wrong route. You get kicked off the mountain, you roll down to the bottom, dust yourself off and start climbing again.

That doesn’t sound like fun.

It’s so, you know, I think my wildest fantasy of writing is something along the lines of this. As I travel to an exotic location, or, not even that exotic, let’s say you got to go to Paris for a month and you write a fantasy novel that’s set in a fantasy sort of version of Paris. And you start it when you get there and your afternoons are spent in a cafe, you know, somewhere on the left bank of the center. And then when you get on the plane to fly back to Canada, you’re also hitting send on the manuscript to the editor who will then fall in love with it. You know, that’s the vision of being a writer that I think I’m always desperately trying to get towards. And so that’s why I write so much now. You know, I write so many books in a given year, a couple of which are meant for publication and a couple of which will literally just be me just trying to get better as a writer so that I can one day hit that point where I can be like, “Yes, I will fly off to Cambodia and I will write a wonderful novel while going on an adventure.”

Well, I think we’re kind of down to the end of the time here. And I think although this did not follow my usual formula of questions, I think you covered pretty much everything I normally ask as we as we chatted back and forth. So, thanks for that.

I apologize for the long answers. I’m a novelist, not a short-story writer.

No, it’s fine. It was great. What are you working on now?

Yeah. So right now, I’m waiting . . . so, soon I’ll be getting notes back on Play of Shadows. I’m going to be starting up the second novel in that series, which is called Our Lady of Blades, which I which is one of those books where I’ve done a lot of climbing up the mountain and then gone, “Wait a second. There’s a there’s a more interesting story to explore here.” I just finished up another mystery novel. I’ve never published a mystery novel, but I’ve written, like, four of them, which is kind of a weird thing to do. But I suppose it allows me to kind of, you know, stretch my writing muscles a little bit. And I’m about to start copyediting on Fall of the Argosi, which is the sequel to Way of the Argosi, which is the one that’s coming out on April 19th and which I hope everyone will enjoy as much as I do.

And where can people find you online?

They can find me at . . . the best way, generally, to find me is at my website, which is decastelle.com. I will see stuff on Twitter and try to respond to it. Facebook is notoriously bad for me. Someone will sent me an incredibly heartfelt message and I don’t see it until six months later. So, my website is usually the best. But, anyway, people try to reach out to me, I will try to respond.

OK well, thanks so much for the conversation. I really enjoyed that. I hope you did too.

I did. Thanks so much for having me on.