Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

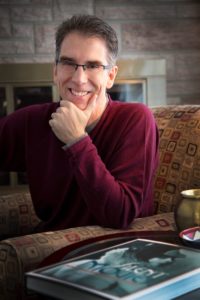

Guest host E.C. Blake interviews Aurora Award-winning writer Edward Willett (the usual host of The Worldshapers), author of more than sixty books of science fiction, fantasy, and non-fiction for readers of all ages, about his creative process, focusing on his newest book, Worldshaper (DAW Books).

About the Guest Host

E.C. Blake is the author of the Masks of Aygrima fantasy trilogy (Masks, Shadows, and Faces) for DAW Books. He was born in New Mexico and lived in Texas before moving to Saskatchewan, where he continues to reside. He has known Edward Willett his entire career.

The Introduction

Edward Willett is the award-winning author of more than sixty books of science fiction, fantasy, and non-fiction for readers of all ages. Besides Worldshaper, other recent novels include the stand-alone science fiction novel The Cityborn (DAW Books) and the five-book Shards of Excalibur YA fantasy series for Coteau Books. In 2002 Willett won the Regina Book Award for best book by a Regina author at the Saskatchewan Book Awards, and in 2009 won the Aurora Award (honoring the best in Canadian science fiction and fantasy) for Best Long-Form Work in English for Marseguro (DAW Books). The sequel, Terra Insegura, was shortlisted for the same award. He has been shortlisted for Saskatchewan Book Awards and Aurora Awards multiple times since.

Edward Willett is the award-winning author of more than sixty books of science fiction, fantasy, and non-fiction for readers of all ages. Besides Worldshaper, other recent novels include the stand-alone science fiction novel The Cityborn (DAW Books) and the five-book Shards of Excalibur YA fantasy series for Coteau Books. In 2002 Willett won the Regina Book Award for best book by a Regina author at the Saskatchewan Book Awards, and in 2009 won the Aurora Award (honoring the best in Canadian science fiction and fantasy) for Best Long-Form Work in English for Marseguro (DAW Books). The sequel, Terra Insegura, was shortlisted for the same award. He has been shortlisted for Saskatchewan Book Awards and Aurora Awards multiple times since.

His nonfiction runs the gamut from local history to science books for children and adults to biographies of people as diverse as Jimi Hendrix and the Ayatollah Khomeini. In addition to writing, he’s a professional actor and singer, who has performed in numerous plays, musicals, and operas.

Willett lives in Regina, Saskatchewan, with his wife, Margaret Anne Hodges, P.Eng., their teenaged daughter, Alice, and their black Siberian cat, Shadowpaw.

Website: www.edwardwillett.com

Twitter: @ewillett

Facebook: edward.willett

Instagram: @ecwillett

The Show

Guest host E.C. Blake, author of the Masks of Aygrima trilogy for DAW Books, introduces himself and explains that Edward Willett has a new book coming out, Worldshaper, and asked E.C. to guest host so he could be a guest on his own podcast. They have a lot in common: both born in New Mexico, both lived in Texas, both moved to Saskatchewan. For some reason, though, E.C. still has a southern twang to his voice.

Guest host E.C. Blake, author of the Masks of Aygrima trilogy for DAW Books, introduces himself and explains that Edward Willett has a new book coming out, Worldshaper, and asked E.C. to guest host so he could be a guest on his own podcast. They have a lot in common: both born in New Mexico, both lived in Texas, both moved to Saskatchewan. For some reason, though, E.C. still has a southern twang to his voice.

E.C. asks Ed which came first for him: the interest in science fiction, or the interest in writing?

Ed says first came his interest in reading, and especially reading science fiction. He learned to read in kindergarten and skipped a grade, so he was always the youngest in his class, which may have helped draw him to books. His two older brothers, Jim and Dwight, both read science fiction, so those kinds of books around the house: one of the earliest books he remembers is Robert Silverberg’s Revolt on Alpha C. He still has the copy he read, which has his brother Dwight’s name in the front of it.

He read his way through all the science fiction he could find in the public library in Weyburn, Saskatchewan, helpfully marked with little yellow stickers with rockets on their spines.

Ed thinks he started writing in elementary school, but the first complete short story he remembers writing was when he was in Grade 7, as something to do on a rainy day. It was called “Kastra Glazz, Hypership Test Pilot” (11-year-old Ed was convinced all characters in science fiction had to have funny names).

Ed’s Mom typed it up and then he gave it to his Grade 7 English teacher, Tony Tunbridge, to read. Tunbridge took it seriously, critiquing it and pointing out problems.This triggered something in Ed: he wanted to keep writing, and make the next thing he wrote better. (He dedicatedThe Citybornto Tony Tunbridge.)

E.C. asked if Ed kept using funny names for characters, and Ed says he did. The next major thing he wrote was a space opera (too short to be a novel, but longer than a short story) called “The Pirate Dilemma,” in which the main characters were named Samuel L. Domms and Roy B. Savexxy.

He and his best friend in high school, John “Scrawney” Smith, used to get together in an empty classroom after school and write, then read to each other what they had written, alternating sentences. They got some funny effects, but more importantly, it kept Ed writing.

He wrote a novel a year in Grades 10, 11, and 12. His English teacher, Mr. Wieb, required students to write a page a day in a notebook. Some kids would just copy stuff, but Ed started writing a story, which became his first novel, The Golden Sword. He wrote Ship from the Unknown and The Slavers of Thok in his subsequent high-school years. He shared the stories with his classmates and discovered he could write stories people enjoyed. Somewhere in there, he decided to become a writer.

However, he didn’t study creative writing in university. He knew it would be hard to make a living as a fiction writer, at least to start with, so instead he studied journalism. He attended Harding University in Searcy, AR, graduating in December 1979.

He went straight home to Saskatchewan and was hired at the weekly Weyburn Review, where he worked as a reporter/photographer for four years, then became news editor (at the age of twenty-four). From there he moved to Regina as communications officer for the brand-new Saskatchewan Science Centre. After five years, he quit to become a fulltime freelance writer.

All through those years, he wrote fiction. His first short sale was a non-science-fiction story to Western People, the magazine supplement of the Western Producer agricultural newspaper. (Later, he sold a science fiction story, “Strange Harvest,” to Western People, probably the only SF story ever published there. That story was later reprinted in On Spec, and even broadcast nationally on CBC Radio.)

He also wrote lots of unpublished novels. It wasn’t until 1997 that he sold his first, Soulworm, which was followed by The Dark Unicorn. Both were nominated for Saskatchewan Book Awards, Soulworm for Best First Novel and The Dark Unicorn for Best Children’s Book.

Ed tells the story of how he started being published by DAW Books. He’d written a book called Lost in Translation, published by Five Star, which sold books to libraries on a subscription basis. The science fiction books for Five Star were packaged by Tekno Books, which was headed up by Martin H. Greenberg (John Helfers was the editor). Greenberg had a connection to DAW, because he’d done some original anthologies for them. He called Ed one morning and said DAW had hole in its publishing schedule and had asked to see some of his Five Star books to see if anything could plug that hole—and DAW had picked Lost in Translation.

Ed got his agent, Ethan Ellenberg, with that contract in hand. His next book for DAW, Marseguro, won the Aurora Award for Best Long-Form Work in English. The award was presented at the 2009 World Science Fiction Convention in Montreal, with Sheila Gilbert and Betsy Wollheim, owners/publishers/editors of DAW, in attendance.

Worldshaper, Ed’s ninth novel for DAW, begins with someone coming through a portal from another world. Then we meet Shawna Keys, who’s living a peaceful life, starting up a new pottery studio in a small Montana city…peaceful, except a stranger has been staring up at her bedroom window in the middle of the night, and there’s a storm coming no one else seems to see. Then her best friend is killed in a terrorist-style attack on a coffee shop. The leader of the attackers calls her by name, touches her, and then is about to shoot her—but she refuses to believe any of this can be happening, and, suddenly, it isn’t. It never happened. But the people who were killed have not only vanished, nobody remembers they ever existed, not even her best friend.

The stranger who has been staring up at her window contacts her, and explains she actually Shaped the world she’s living in it—it isn’t the real world at all, but a construct. He tells her that the attacker from the coffee shop, called the Adversary, is going to take over her world and all other myriad Shaped worlds in what he calls the Labyrinth, unless she can visit them, contact their Shapers, retrieve the knowledge of the Shaping of those worlds, and convey that knowledge to Ygrair, the woman at the heart of the Labyrinth, who found it, opened it, and gave the Shapers their worlds to Shape.

E.C. asks what the typical novel-seed is for Ed.

Ed says it can be a number of things. For example, his science-fiction novel The Cityborn began with a mental image of a towering city, squatting over a canyon filled with a massive garbage dump, in which there are people scavenging to survive.

Ed says it can be a number of things. For example, his science-fiction novel The Cityborn began with a mental image of a towering city, squatting over a canyon filled with a massive garbage dump, in which there are people scavenging to survive.

His YA science-fiction novel Andy Nebula: Interstellar Rock Star came out of an exhibit at the Saskatchewan Science Centre about how memory works, combined with a news item about teenaged Japanese pop stars who were one-hit wonders. In the book, there are aliens whose memory works differently, and Andy is plucked off the street to become a one-hit superstar—it’s drugs, rock and roll, and aliens for teenagers.

For Worldshaper, the trigger was wondering what it would be like if the creators of fictional worlds could actually live in them.

Worldshaper was originally conceived as a fantasy novel, set in a medieval village in an endless, inescapable valley, along which were strung caves that were portals into different worlds. Despite the changes to that concept, the main character has always been a potter: the perfect metaphor for a Shaper.

Ed’s process of developing a story is to ask himself questions In The Cityborn, who are those people living in the garbage dump? Why are they there? Why has this city been fouling its environment for so long? Where did it come from? Who lives inside it? Conflict, and hence plot, arises from the answers to those questions: the people in the garbage want into the city. What would they do if someone from the top of the city, where the rich people would logically live, ended up down in the garbage dump? Every answered question presents other questions that must be answered.

Ed hastens to add it’s not really as formal a process as it sounds: a lot of the asking and answering of questions happens quickly inside Ed’s head as he types, but that’s how he interprets what he’s doing.

E.C. asks how detailed a plan Ed has before he starts writing. Ed says he writes a four- or five-page synopsis, not a chapter-by-chapter outline, just a rough description.

He doesn’t follow that synopsis particularly closely, either. The overall shape of the book is there, but the writing process may take him in a very different direction. He mentions how in Terra Insegura, sequel to Marseguro, a character introduced only because a viewpoint character was needed in space while everyone else was on the surface of the planet became so important that Ed had to replot everything about two-thirds of the way in.

The synopsis is just a guide to keep him on track, and maybe provide a hint of a way forward when he runs into a bump in the road.

E.C. asks how much of Ed’s worldshaping is done on the fly.

Ed says when he’s writing, he writes almost as fast as he types. He figures he averages 1,000 words an hour or more. “Things just come out of your head, onto the paper.” It’s hard for him to figure out exactly how that process works because it’s so seamless.

What flows out through his fingers feeds on itself. One sentence leads to another, which leads to new characters, new problems, new solutions.

Ed says he finds this “really fascinating,” and that’s why he asks all the authors he talks to on The Worldshapers about their writing process. It also ties into Worldshaper, because Shawna, is often trying to Shape her world on the fly, and sometimes it goes awry—just as it does with authors.

E.C. asks about Ed’s research process, and Ed says there was quite a bit of research involved in Worldshaper, because it’s set in a world very much like ours. He researched things like helicopters, radio call-signs, camping equipment, and what the surveyors’ mark at the top of a pass would look like—an important detail which makes Shawna wonder why this thing she didn’t even know existed exists in the world she supposedly Shaped.

E.C. asks how Ed develops characters. Ed says for Worldshaper there were obviously three characters who had to exist—the Shaper (Shawna Keys), the Mysterious Stranger (Karl Yatsar), who clue her and the readers into what’s going on, and the antagonist (the Adversary).

Ed originally thought the whole book would be first-person, from Shawna’s POV, but in consultation with his editor, Sheila Gilbert, he realized he needed to make Karl and the Adversary POV characters as well. Karl’s POV is third-person, fairly close in, while the Adversary’s POV is a more detached third-person. Mixing that with Shawna’s first-person narrative was an interesting challenge.

Ed says that, possibly because he began writing on a typewriter, he writes a complete first draft and then rewrites, typically focusing in the second draft in on sprucing up language and dialogue. He estimated his first draft is maybe eighty percent of the way to how the published novel will read, his own rewrite gets it to ninety or ninety-five percent, and editorial suggestions provide the impetus for the last five percent.

Ed has worked with a great many editors. Sheila Gilbert at DAW, he says, is particularly good at discovering the weakness in plot, characterization, back story, and asking the author to answer questions either not asked (or, more likely, ignored or papered over) during the writing process. Worldshaper had more editorial input than most of Ed’s books because of the need for the initial set-up to support a (hopefully) long-running series.

Ed says the great thing about the series is that, while the first world is much like ours, future worlds won’t be. As in the original Star Trek and Doctor Who, the overarching storyline is an excuse to play in all kinds of different worlds and settings. Books could have a film noir setting, or a vampire setting—the possibilities are endless.

E.C. asks if there are any embarrassing errors or omissions editors have found. Ed says there was a big one in Worldshaper. The copyeditor pointed out that when characters sailed out into the open ocean, they were described as doing so from a place along the Washington coastline that would actually have taken them into Puget Sound, where they would very soon have encountered land again. That was fixed by relocating the scene much further south along the West Coast.

That’s an example of the value of editors!

E.C. asks why Ed is using the term “worldshaping” for the podcast, instead of the more commonly used term worldbuilding.

Ed explains that, apart from the marketing synergy of the podcast and the book having similar names, he feels worldshaping better describes what writers do. He points out writers aren’t really building new worlds, they’re shaping worlds from the raw material of the real world. After all, we have nothing else to draw on. The image of the potter taking clay and shaping it into something interesting seems to him a better metaphor than building a world.

Ed goes on to say that he feels strongly that literary writers’ fictional worlds are every bit as much made up as those of science fiction and fantasy. The real world cannot be contained within a construction of words, he says. “The symbol is not the thing.” So while literary fiction may appearto be set in a world more like ours than the worlds of science fiction and fantasy, that’s an illusion—those worlds are equally fictional. The only difference is that in science fiction and fantasy, authors are taking their raw material and shaping it more extravagantly.

Ed says the title of the book came first, not the title of the podcast, but that he’s been thinking of a podcast or something similar for a long time, in which he can use his journalistic familiarity with interviewing people to compare notes with other writers of science fiction and fantasy about the process of creating the stuff they create, in the hope other authors and readers might find it interesting.

E.C. asks Ed to answer the question, “Why do we write this stuff?”

Curiosity is innate in human beings, Ed replies: its part of the brain. The theological answer, he continues, is that God created man in His image, and since God creates things, so do we. This is Tolkien’s concept of “sub-creation.” As he put it, “We make still by the law in which we’re made.”

Evolutionarily, Ed says, there’s clearly a survival benefit to being creative, thinking up new ways to do things. Our ancestors survived because they were creative, and that creativity has been handed down.

On a personal level, though, Ed says he writes stories “because it’s fun,” and he thinks that’s why most writers write. After all, most writers start as kids, and what do kids do? They play. Writers go from building sandcastles in sandboxes to building castles in fantasy realms. Yes, writing professionally is work…but at heart, it’s play.

E.C. asks if Ed is trying to shape the real world through his fiction. Ed says he doesn’t really have any control over it, noting that very few authors’ work has really changed the world, so that, while aspiring to change the world is a great goal, it’s not necessarily a realistic one.

Ed thinks that if he’s changing the world it’s one person at a time, by entertaining readers, adding enjoyment to their lives, maybe making them a little happier. If along the way they find some ideas in his fiction that change the way they think about the world, or feel better about the world, that’s good, too. But all he can really do is write the books he wants to write to the best of his ability, and hope that readers enjoy them.

E.C. asks what’s coming next.

Ed says he’ll soon be writing Master of the World, Book 2 of the Worldshapersseries. In addition, he recently wrote a middle-grade modern-day fantasy, The Fire Boy, currently with his agent, and has agreed to write a horror-flavoured YA novel for another publisher (still nameless because no contract has been signed yet). In addition, he’s writing a play-with-music, The Music Shoppe, for Reginal Lyric Musical Theatre.

Ed says he’s done quite a bit of theatre: he’s a member of Canadian Actors’ Equity and has done a certain amount if professional stage work (and a lot more just for fun). He also sings with choirs: he’s sung with the Canadian Chamber Choir and currently is a member of the Prairie Chamber Choir.

Finally, E.C. asks why Ed always mentions Shadowpaw the Siberian cat in his biography, and Ed explains it’s partly because Shadowpaw has a literary history: Betsy Wollheim from DAW picked him out, and Ed went down to New York to visit DAW and pick Shadowpaw up. Shadowpaw’s name and photo also graces the new books from Shadowpaw Press, Ed’s new publishing company, which has brought out his short story collection Paths to the Stars and will be releasing other of his work—and a few other things—going forward.

And that’s that!

E.C. doesn’t imagine he’ll be guest hosting again, but he enjoyed it.

Art says he was inspired to write fantasy by The Hobbit. His Grade 4 teacher read it out loud to his class, and he says it was the first book read to them that he really “fell into.” In fact, he was so “agog” at it that when his parents took him away from school for a week to go on a family trip to Disneyland he actually felt kind of sad he was going to miss a whole week of the The Hobbit.

Art says he was inspired to write fantasy by The Hobbit. His Grade 4 teacher read it out loud to his class, and he says it was the first book read to them that he really “fell into.” In fact, he was so “agog” at it that when his parents took him away from school for a week to go on a family trip to Disneyland he actually felt kind of sad he was going to miss a whole week of the The Hobbit. Julie Czerneda was born in Exeter, Ontario, and grew up on air force bases, her family moving with each transfer, from Ontario to Prince Edward Island and finally to Nova Scotia. When her father became a civilian, the family moved to Ontario, settling in what was then a rural setting near the shores of Lake Ontario (and is now that not-so-rural setting known as Mississauga.

Julie Czerneda was born in Exeter, Ontario, and grew up on air force bases, her family moving with each transfer, from Ontario to Prince Edward Island and finally to Nova Scotia. When her father became a civilian, the family moved to Ontario, settling in what was then a rural setting near the shores of Lake Ontario (and is now that not-so-rural setting known as Mississauga. Still, the prospect of writing a fantasy novel terrified her. She finally did (

Still, the prospect of writing a fantasy novel terrified her. She finally did ( She likes to put as much as she can into a story so she can draw on it latter—such as the giant lobsteresque alien from

She likes to put as much as she can into a story so she can draw on it latter—such as the giant lobsteresque alien from  Sometimes minor characters threaten to take over a book. Julie remembers that in her second book in The Clan Chronicles,

Sometimes minor characters threaten to take over a book. Julie remembers that in her second book in The Clan Chronicles,  John Scalzi was born in California in 1969 and currently lives in Bradford, OH. He studied philosophy at the University of Chicago, which is where he began his freelance writing career. He wrote film reviews and was a newspaper columnist for a few years, and in 1996 was hired by

John Scalzi was born in California in 1969 and currently lives in Bradford, OH. He studied philosophy at the University of Chicago, which is where he began his freelance writing career. He wrote film reviews and was a newspaper columnist for a few years, and in 1996 was hired by

Although we’ll be discussing her book

Although we’ll be discussing her book  Robert James Sawyer is a Canadian science fiction writer, born in Ottawa and now living in Mississauga. He’s the author of twenty-three novels and innumerable short stories (well, not literally, obviously they’re numerable, but it’s a large number), and is the most-awarded science fiction writer of all time, said awards including the

Robert James Sawyer is a Canadian science fiction writer, born in Ottawa and now living in Mississauga. He’s the author of twenty-three novels and innumerable short stories (well, not literally, obviously they’re numerable, but it’s a large number), and is the most-awarded science fiction writer of all time, said awards including the