Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

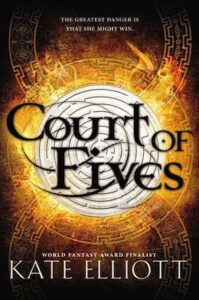

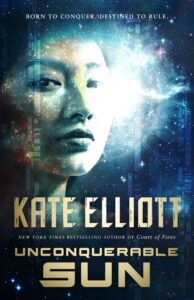

An hour-long-plus conversation with Kate Elliott, author of Unconquerable Sun, “gender-swapped Alexander the Great in space,” and many others, including the Crown of Stars epic fantasy series, the Afro-Celtic post-Roman alt-history fantasy with lawyer-dinosaurs, Cold Magic, and sequels, the science fiction novels of the Jaran, the YA fantasy Court of Fives, and the epic fantasy Crossroads Trilogy,

Websites

www.kateelliott.com

imakeupworlds.com

Twitter

@KateElliottSFF

The Introduction

Kate Elliott has been writing stories since she was nine years old, which has led her to believe that writing like breathing, keeps her alive. As a child in rural Oregon, she made up stories because she longed to escape to a world of lurid adventure fiction. Her most recent is Unconquerable Sun, “gender-swapped Alexander the Great in space.”

She is also known for her Crown of Stars epic fantasy series, the Afro-Celtic post-Roman alt-history fantasy with lawyer-dinosaurs, Cold Magic, and sequels, the science fiction novels of the Jaran and the YA fantasy Court of Fives, and the epic- fantasy Crossroads Trilogy, with giant justice eagles. Her particular focus is immersive world-building and centering women in epic stories of adventure and transformative cultural change.

She lives in Hawaii, where she paddles outrigger canoes and spoils her schnauzer.

So, Kate, welcome to The Worldshapers.

Ed, thank you so much. I want to say that at the moment, the usual club outrigger canoe practice has been cancelled or suspended, I’ll say, due to the pandemic. So, that’s the one thing that I’m not paddling my usual six-man six-feet canoe three to four times a week.

Well, here in the middle of the continent, we don’t have a lot of that anyway. So, I hadn’t really noticed that that was one of the things that had been cancelled. Well, we have met because we’ve both been published by DAW and we met at one of the lovely DAW dinners. For your DAW books is Sheila your editor, Sheila Gilbert?

Yes, yeah.

And she’s mine, as well. So, we share that.

She’s a fantastic editor.

Yes, she certainly is. So, I’m going to start, as I always do, by taking you—this has become a cliche on the program, “back into the mists of time,z’ and I’m going to put reverb on it. One of these days, I’m going to do that, “back into the mists of time,” to find out…well, I know from your little bio that you’ve been writing since you were very young. So, how did you get interested in writing and…well, reading and writing and all that kind of stuff? What led you down the garden path to being a writer?

You know, this is the big question, isn’t it? And I think there’s an even deeper question that goes even below that, which is like, why do human beings create at all? What is the, let’s say, the evolutionary advantage of the way our minds work, which is sometimes in amazing ways and sometimes it really debilitating ways. I think they’re all kind of linked. Why? I guess I would say is that I believe that human beings, part of what makes us who we are, is pattern making and creativity. And there would be survival mechanism in that, in, like, seeing that we could eat this food, right, or seeing that if these seeds dropped here, in the next season, when I came back, there was stuff here I could eat. So, that then develops to language and to all the other ways that we think about, not just art, but about science and about religion, all the ways that we understand the world.

So really, the question I would ask is, why do some people not feel they’re creative, which to me is a tragedy and something I think that is imposed on people from the outside, not part of who people are, really, kind of at root? But then, the other question is, why did I decide to write? Why did I want to tell stories as opposed to designing clothes or playing music or woodworking and building furniture? And I don’t know. I could say maybe why I didn’t do some of the other things. So, it’s easier to define that negatively, in a way. But I just know, from a very early age, I liked to draw maps, and I liked to draw large underground domiciles where, you know, where thousands of people were living. And I was doing that at age 10, 11. I don’t know why. It just intrigued me. I would tape pieces of paper together and then draw these just huge architectural things that had nothing to do with how anything would really be built. But I enjoyed it. And that went to maps, and then I guess, partly because I grew up in rural Oregon and I loved being outdoors, but it was also kind of boring. So, when I started reading science fiction and fantasy, then, of course, as a teenager, I was like, “Oh, I want to live science fiction and fantasy.” And since I couldn’t figure out a portal, I couldn’t figure out where the portal was to that other world that I really wanted to be in, the best portal I had was to write stories.

Yeah, kids in stories are always stumbling these things, and I was never able to find one either. It seemed totally unfair.

I know, right?

My wardrobe, I didn’t have a wardrobe, but my closet didn’t lead anywhere. And, you know, there wasn’t any hole in the backyard that led to the world of Óg or whatever. Yeah, it’s very unfair. And tornadoes are a terrible means of transportation.

I haven’t, yeah. I’ve actually not experienced a tornado yet. Who knows? But I would like one, like, if I would go out hiking…my family camped a lot when I was a kid. We would go on camping trips…and I would always look for those two trees growing close together whose branches intertwine, and I would say, “Maybe this is the one. I’ll step through, and it will be the portal into that other world.” But, yeah.

What were some of the books that kind of woke you up to science fiction and fantasy when you started reading them?

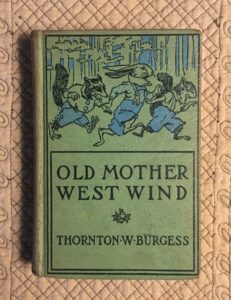

The earliest chapter books I remember reading are ones…they were these editions of books that my father had read as a child that we still had, and they were by Thornton Burgess, the Mother West Wind stories. And most people my age aren’t aware of them. And I only knew them because they were in the house. And I think today he’s probably mostly forgotten. But back in the day, when my dad was young, these were stories written, set in the…I can’t even remember…the Wild Woods. Anyway, they were in the woods, and everything was anthropomorphized, so that Mother West Wind was…she had thoughts, and she had the merry little breezes, and then all the animals, and they all had these little adventures. And I read those obsessively when I was very, very young. And I always feel like they were my gateway into this idea that there could be this fantastic other world of things that I wasn’t aware of.

And from there, I would say, I read Scholastic Book Fair books that had fantasy in them or science fiction. I couldn’t give you any particular titles now. The big one for me was reading Lord of the Rings at 13, and that kind of kicked me onto the path that I then never left. Also, Ray Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles, that was…those were two in what was then called junior high school, now would be called middle school. And then, you know, in high school, I began to read Le Guin and just…

Yeah, I think we’re almost exactly the same age, and that’s a very familiar set of books and pathway. It’s almost the same ages at which I was reading those things, as well.

Yeah.

But you started writing stories, as well, very early. Did you share those stories with other people, or was it just kind of a solitary thing you did to entertain yourself?

Um, when I was in ninth grade, I think it was, my best friend and I wrote kind of a shared set of stories. We drew a map and then wrote a shared set of stories. And interestingly, that set of stories, there were these two main characters, one was hers and one was mine, and they were both men. And that’s like…because when I was 14, that’s who was in those stories. So, if you were going to write a fantasy story, it had to be about men. But by the next year, I had switched over and started writing stories about women. And I wrote a lot in high school, and I’m not sure that anybody read it.

I always ask that question because I wrote in high school, three novels in high school, and I did share them with my classmates, and it was one of the things that actually told me maybe I could tell stories. So, I always like to ask that question, and I get differing answers from different authors. Some people say, “Oh, I would never have shared anything at that level.” Have you…well, OK, here’s another question. Have you shared it since? Has anybody read your juvenilia?

No, not a chance. Not a chance. Although I have recently…I’m actually really intrigued that you shared the books with your friends, which I think is fantastic. And they read them all, and they asked for more and wanted to read the next one?

Yeah. Well, they weren’t a series, but I had a teacher—I had more than one teacher!—but I had one particular teacher, we were required to keep a writing book, so you had to write a page of something every day. And most kids were copying stuff or, you know, not doing much with it. But I started writing The Golden Sword when I was 14 years old, and it was only for one semester that we had that class. And it’s all dated in the book I was writing it. And so, you get to December and the dates at the top stop, but the story just keeps going because I was way ahead and going on to the end. And I learned to type in Grade 10, and as soon as I learned to type—I was just dying to learn to type—and as soon as I learnt how to type, I would type these things up, and I bound them up, and I handed them out to my classmates. And people really seemed to enjoy them. So, it was kind of a thing for me to kind of help point me in the direction of being a writer.

That’s…I just think that’s fantastic. I also remember learning to type in high school and how great it was because I could type so fast. You know, it’s interesting. I didn’t share as much. I wouldn’t have shared it. I think a lot of it was too personal to me. I did find, some years ago, I hunted down and found the journal I kept when I was 16, which was not a normal journal because it was me pretending to be a person going…I had drawn this map, it was like my special map, my, like, the map that the portal would take me to, right?. And then this journal was me going to different places on the map and describing them and describing the journey, and then whatever else a 16-year-old would put in there. And before I wrote Court of Fives, or maybe in the early stages of writing Court of Fives, which of course is a young adult novel, I thought, “Oh, you know what? I’m going to go back and see if I can gain some inspiration and insight into my 16-year-old self.” I could not get through two pages of it, not because it was badly written, but because I was 16 when I wrote it. And it wasn’t bad. I’m not saying that in any way to criticize myself, but I was just like, “Whoa, whoa, man!” That mindset was, like, so much for me. It was so intense. But it was interesting to realize how intense being a teenager is.

As they say, the past is a different country, and it’s true of your own past as well as some of the world’s past, I think.

Well, I could see me. I mean, it was me. I recognized me. And I recognized things that are very much still me in it. But, wow. Yeah. It was enlightening. And then, another thing that happened recently is…my first full novel, I wrote in high school, and I was talking to my editor about it, and she said, “Oh, you should put that up on Wattpad.” So, I again dug down, down deep, deep, and I found it. And I’ve been looking at it and thinking, “I wonder if this would be worth cleaning up a little and putting on Wattpad just for the fun of it.”

It’s funny you should say that because I’ve been looking at my magnum opus from high school, which I wrote when I was sixteen.

Which is called?

Slavers of Thok.

Oh, wow.

It’s a big fantasy novel. It has a map because, of course, as you know very well, maps are essential to a true fantasy novel.

Yeah.

With really terrible place names. And I typed it, so I was able to do an optical character recognition, kind of, because my ribbon was dim in a lot of places, and I have been thinking the same thing. I might just throw it up somewhere and see what comes of it. It’s not horrible in some places. It’s a pretty good story, actually. So, we’ll see.

I think we’re probably better. I didn’t actually start reading mine. I just found it. And there was a lot of it, single-spaced on legal-size paper. A lot of it. Both sides. So, but yeah, I, I think we’re better, and also inexperienced, as teenage writers, better than we perhaps think we are and not as good as we think we are. So, it kind of goes hand in hand, right?

I think that describes it exactly. So, you left Oregon to go to university in California, I believe.

Ed, I have to say, sorry, it’s Oregon.

So, what am I saying?

You’re saying OreGON.

Oh, sorry.

Sorry. No, no, I don’t…I hate to be pedantic about it, but…

No, no. It’s hilarious, because I live in Saskatchewan and nobody can pronounce Saskatchewan.

Saskatchewan. Saskatchewan.

So, people say SaskatcheWAN, just like I’m saying, OreGON. Oregon. There you go.

Oregon. Perfect. It’s just kind of like….yeah.

And the other one is Newfoundland. NewfoundLAND. You have to emphasize the land. So, yeah, there’s a lot of things like that. OK, Oregon. So, you left Oregon and went to California. What did you study in college? Did you study writing or something completely different?

Well, college was strange for me. I went to Mills College in Oakland, California. I only actually went there two years. My senior year in high school, I took enough college class credit classes at the local community college that I came in with a full year already. And then I went one year to Mills, and I didn’t love it. So, the next year I did my, what was by then my junior year, abroad at the University of Wales in Wales, at Bangor, Wales. Then I worked for a year at the BBC in the radio division on a student work visa. And then I came back and finished my degree at Mills. So, I had kind of an eclectic…I did some history, I did some anthropology, and I ended up majoring in English, mostly because that was what I had enough credits to do. So…and I did get a…I think I got like a minor or a…I didn’t call it a minor, but a minor in creative writing, which frankly was kind of a waste of time.

That was my next question.

Well, they were so full of, you know, why are…these were literally the people saying to me, “Why are you writing science fiction and fantasy? You should be writing real literature.” So, it wasn’t…you know, it’s just not useful to take courses from people like that.

I’ve asked that question of a lot of the writers I’ve interviewed, and of those who have taken formal writing classes, I would say there are more that say that than say that they were really helpful to them, which I always find interesting.

Well, I think it could have been helpful if people hadn’t been so dismissive of science fiction and fantasy.

Now, I also wanted to mention, because I’ve seen, in things I’ve read about you, that you were active in Society for Creative Anachronism, and I dabbled in that. But it not very active where I am here now. And that’s where you met your husband, isn’t it?

Well, I’m no longer married, but yeah, yeah. But what I loved about the SCA, I wasn’t that interested in the re-creation aspects. I’m an athlete. So, I was really what they called in the ACA in those days, they called a stick jock. I just went there to fight, to put on armor and fight, so that’s what…I did that, and actually, that was pretty great. And it was useful as a fantasy writer, not because we were actually, you know…well, I did get a broken arm once…but it was useful because it gave me a sense of how it feels to have people around you, how it feels to be lying wounded on a battlefield, not that I was really wounded, but how space worked, the physical function of space, people nearby, people far away, what you could hear, what the sun might feel like, you know, how skirmishes might act, how they would run. So, that was useful information for me to have, especially when I wrote Crown of Stars, which is a seven-volume epic fantasy series set in a…well, it’s really inspired by early medieval Germany. So, smaller units, you didn’t have big armies. And I really got a lot of use out of that, in that series, of that experience of fighting in the SCA. So, I’m glad I did it.

Has the history and anthropology you studied also come in useful in your writing? I would expect they would.

Well, I still read a lot of…I mean, history is my main reading. The thing I read most is history. My dad was a history teacher, and so I’m very much still reading history and anthropology. I consider myself still a student of it, I guess I would say.

And that figures into your worldbuilding and everything?

Oh, absolutely.

Well, let’s talk about how you broke in, then. How did you go from being, you know, writing, but then writing professionally? How did that all work for you?

So, you know, when I broke in back in the day, things were very different. Social media didn’t exist. The Internet was in it…even in its early days, you could get together. I got on, like, bulletin boards like Genie, back in the late eighties. And it was very much a query culture. You would write to agents and hope someone would want to represent you, and then they would send, you know, your work to editors. Some publishers still had slush piles. So, I did what a lot of people did. I wrote around until I finally got an agent who was willing to represent me and then they eventually sold something of mine, and then it just proceeded from there. I later switched agents. So…does that explain enough? I don’t know that it’s a particularly relevant story in terms of what people can know today. It just…you just have to be persistent.

Yeah. And I’m from the same era, but I didn’t break in as early as you did, but I was certainly going through that whole process as well. So, yeah,

And I also wanted to say that I didn’t come up come in through the science fiction/fantasy community. I know a fair number of people who were fans first, which is another way. I mean, there’s no, like…there is no one right way or better way to do it. So, I know people who came in through fandom. And they were in fandom and then they got published. And that’s another way to do it. I’d never attended a science fiction/fantasy convention until after I was published. So, they weren’t anything I really knew about until then.

We didn’t have a lot of them around Weyburn, Saskatchewan, where I was growing up. I think the first one I was at was when WorldCon was in Winnipeg. That was the first major convention I was at.

Yeah, yeah. So, I didn’t…I just wasn’t aware of things like that. And I was probably a little too reserved to ever have gone just on my own anyway.

Well, let’s talk about your making of books, which is what this podcast is about. And also, you know, you already mentioned that everybody does it differently. And that’s one thing I’ve certainly found out in talking to…I think you’ll be like my sixtieth author or something like that I’ve interviewed.

Wow.

Everybody does it differently. But let’s find out how you do it, and we’ll focus on Unconquerable Sun, which is the new one. And I’ve delved into it. I haven’t finished it, which is fine because I’m going to get you to give a synopsis of it without giving any spoilers.

Well, I just say what the pitch is, which is it is gender-bent Alexander the Great in space.

That’s pretty much a perfect elevator pitch.

It is. And I’m not even good at elevator pitches, but that is literally what it is. So, the first book is what I would call young Alexander. So, it takes place in a set period of time. It takes place…there’s an opening sequence of things and then a time skip, and then the rest of the book takes place in about two weeks. Based on our understanding of a week, not on theirs. Right?

That’s a fast pace.

Yeah.

For a big space-opera type story.

Yeah. So, it’s…yeah. I’m not good at describing plots, that’s why I…

Well, I think the pitch does a good job of presenting an intriguing set-up, that’s for sure. And I have enjoyed what I’ve read of it, delving into it. How many…well, it’s obviously more than one book. How many books do you envision in this?

Well, I do want to say that the first book is a complete story. It doesn’t end on a cliff-hanger, it’s a complete story. Which I did on purpose because I think if one is going to use…I’ve written…let me just backtrack a moment to say that I have, of course, written trilogies that had cliff-hangers at the end of every volume. And with this one, I wanted to try to give people the chance to read a book, feel really satisfied at the end that they had read a complete story, things had been resolved, but that there were other threads now that they would want to follow. And that was my intention all along with book one, and that’s why I call it Young Alexander, because it takes place at what would have been the Court of Macedon, more or less. Yeah. So…where were we going with this question?

How many books do you envision eventually?

A trilogy.

Trilogy.

Yeah.

All right, so we have our elevator pitch here, which almost sounds like the idea that came to you to start this whole process. But what was the genesis of this and the kernel that this grew from? And is that typical of the way that you start growing stories?

It isn’t, because actually, it did kind of come from the, “What if I did gender-bend Alexander the Great in space?” And normally, my stories start with, like, an image or a moment, as if almost as if seen in a motion-picture sense. So, for example, Crown of Stars, which is seven volumes, the seed of the idea for that was me, in my head, seeing a young man who’s walking between the village where he was born and grew up, as far as he knows, walking over…it’s on the ocean, and he’s walking up and over a ridge pathway that leads, on the other side of the ridge, to a monastery, where he’s taking something for the monks that his aunt is sending him with. And as he’s walking up over them, he sees this massive storm coming in, way too fast, off the sea, and as it overtakes him on the ridge, a woman, a middle-aged woman wearing battered armor, with a sword, rides out of the storm toward him. That’s the beginning of that book. That’s the seed image of that book. Everything else grows out of that.

Or Cold Magic, the Spirit Walker trilogy, the first book is called Cold Magic. This is the afro-Celtic post-Roman lawyer-dinosaur book. So with that one, it’s similar, in the sense that, in my mind, I saw these two young women sitting in a paned, p.a.n.e.d, like windowpane, window seat, looking out over a courtyard as a carriage arrives, and they know that something unpleasant or something that means something bad for them…they have a bad feeling about that carriage and what or who is coming in with that carriage. So that again…and that’s the whole seed of that story. And in both of those cases, what you see is, you have a person with something about to meet them. You know, there’s your conflict, right?

And then, but also in my mind’s eye, what I see also tells me something about the kind of the general historical era it’s going to be in. So, on the one hand, the armor she’s wearing is chainmail, it’s not plate. So now we’re going earlier, and it’s there’s a medieval sense because there’s a monastery. So, now I know that I’m in a more early medieval period. And the other one there is a carriage and the way they’re dressed, and I could see that it was kind of a late 18th-, early 19th-century setting.

But with gender-bent Alexander the Great in space, that’s a very concept-driven idea. And I’m not, in that sense, concept driven. I’m more like emotional-moment, meeting-a-landscape, meeting-a-conflict driven. That’s where most of my stories come out of. So, for me, with that concept—and there’s, in a way, more to it than that, but I won’t…you know, I had just written Court of…well, first of all, I have a son named Alexander, you know, so I’ve been interested in the story. And he is named after Alexander the Great. And so, I’ve been interested in the story of Alexander the Great for a long time, just in general. But then when I wrote the young adult fantasy trilogy, Court of Fives, that…I drew a lot of inspiration from the Hellenistic-era Egypt, in which people from Macedonia, Macedonians, came and established themselves as the rulers of Egypt over this large indigenous population. And I…and the last Ptolemaic, the last of those rulers, was Cleopatra, who we…she was actually the seventh Cleopatra of that lineage, but she’s the Cleopatra we all know, right?

So, writing that…and I did so much reading about the Hellenistic era, which is that period…it’s the period basically from Alexander to Cleopatra. And that’s called the Hellenistic period, when the Hellenic, the Greek, culture was spread throughout the Mediterranean. And it was kind of, it was kind of the multinational American pop Hollywood culture of its day. That’s a terrible, terrible simplification, but there’s a similar sense. So…and I think that kind of rolled me toward gender-bent Alexander the Great in space, if you see what I mean.

But conceptually, what I had to do then was to say, “OK, I’m going to do it like this. I want to do this concept. But now, what do I want it to mean? What do I want to do with that concept?” And that’s, for me, a different direction to build a universe from than what I’m used to, because in the other cases it’s more like, “Oh, I see, I’m in this place already. Now I need to discover it by writing it and deciding what aspects I want to see. And where does this road go to, right?” But in this case, I could have done anything because I didn’t have that visual seed image already in it.

So, what was your approach to planning it out, and how does that match up with the usual approach? Do you do a lot of outlining, or how does that work for you?

Well, I’m not really a…I outline, and I don’t outline. So, I kind of do both. But I can actually. I can. So, what I had to do was to ask myself specific questions. And there’s two main questions I had to ask. So, the first one is, if I’m going to make the Alexander character a woman, the first question I have to ask myself is, “How does this princess…?” Well, actually, let me step back to a third question. So, the first thing I have to do is I have to say, “OK, Alexander the Great as a story only works if I have a kind of a monarchy, and I have a lot of war.” So, either you’re going to want to write that story or not, right? And, you know, I get tired of writing about monarchies. I’ve written stories that weren’t about monarchies because I was like, “I’m done with writing about monarchy.” So, that was partly an issue for me. It was like, “Do I really want to go back to…do I really want to do this again?” But I really wanted to do it. I really loved the concept. So, that was my first thing, was to accept that it’s not that story if you don’t have those things. So…do you see what I’m saying? It’s like, “I want to write a Sherlock Holmes story, but he doesn’t solve any of the mysteries.” Then it’s not a Sherlock Holmes story.

Yeah, exactly.

Or if he’s super well-adjusted about everything, well, then it’s not really a Sherlock Holmes story, you know, and he doesn’t have his sidekick, Watson. Well, I mean, part of that…that story is based also on their relationship. So, when you’re taking something, a concept like that, that has a relationship to things that readers know, but that, you know, there’s a—for me, and I’m not saying anybody has to do this—but for me, there is…I have to decide what essential things are absolutely necessary to make it still that story or to be a Sherlock Holmes retelling, right? What do I have to have for that? So, what would I have to have for it to be an Alexander the Great retelling? So, that was stage one.

Stage two was, “What am I going to do with the princess?” Is she going to be the…because, you know, Macedon, like the ancient Greece of its time, was a patriarchal society, where men ruled. Now, women had more scope, in Macedon especially, and women had more scope in the Hellenistic era. It’s quite interesting. And for those who are interested in this issue, please read Elizabeth Carney. I highly recommend her book, Women and Monarchy in Macedonia. It’s an easy read. She really knows her stuff.

I’ll put a link to it in the transcript when I do this.

Yeah, do. Because there’s a lot more interesting stuff going on than one is generally taught in school and then, you know, and the stereotype of what it was like. But nevertheless, it was a patriarchal society. So, this question two is, “Is she the scrappy princess who proves that she’s worth ruling even though she has to fight against misogyny and sexism?” Or…one of the most important things about the story of Alexander is that he was raised as heir in a society where it was absolutely assumed that he was worthy of being heir, right? He had to prove his competency to lead troops in battle because it was, Macedonia, at that time, was very focused on war. The reason that Alexander’s father, Philip, became king was because his older brother died with a, like, a three-year-old son, and a three-year-old son can’t lead an army. So, Philip became king.

And this is actually common. And this is true in, like, Anglo-Saxon England as well. Alfred the Great, whom many of us have heard of, became King because he was like the fifth or sixth of six brothers. And the other ones all died one by one, killed in wars with the Vikings. And any children they left were too young to lead armies. And so, it passed down the brother line, not father-to-son line. And that’s an important difference in how rulership is seen. So…and that’s where the history comes in useful, right/ Just to know that that exists, that it doesn’t have to go father to infant son. It can go father to brother, or it can go adult to adult.

But anyway, one of the things about Alexander—sorry I’m so geeky about history—but one of the things about Alexander is he was made for the moment, everything about his life, who he was, his capabilities, made him for that moment. He didn’t make that moment. He was there, the right person at the right time. And when I looked at the story, I thought, “You know, if the scrappy princess fights against sexism to prove her worth, it’s not that story anymore, is it?” So, that was the first thing, the first decision, the first worldbuilding thing that fell into place was, it’s absolutely commonplace. They don’t care in this society. Gender doesn’t matter in that sense.

So…and, in fact, I swap a lot of, you know, I spin a lot of gender. So, the Phillip character is…so the Alexander character’s name Sun, like the sun in the Sky, and her mother, Eirini, which means peace, by the way, it’s an ironic name, is the Philip analogue. So…but Eirini in the book has three older brothers. And, in fact, Philip had two older brothers and they had a sister, these three brothers. So that’s kind of borrowed from history, as well. And they were all…they all ruled before her but were killed in war, and it came to her down that line. So, deciding that that aspect of it was that rulership wasn’t based on gender, it wasn’t that only women ruled or only men ruled, it was, you know, the most competent person ruled if they were part of the royal house. So, that made that decision for me.

And then, the third question I asked myself was, “Am I going to create a setting, a space opera setting, that is completely unattached to Earth?” It’s kind of like Star Wars, right? There’s nothing in Star—I mean, except for the fact that it’s written by us and we see it—it’s not—there’s no references to Earth that I know of in the Star Wars universe.

No.

So, I could either do that, or I could do that thing where there are connections to Earth. And for my own purposes, mostly because, in large part because I thought it would be more fun because I really like Easter eggs and stories, I decided to go for a connection with Earth and then I had to decide how I wanted that connection to be. Did I want it to be a close connection or a very, very distant connection? And my decision was to make, to set this, in the far, far future, very far away, you know, an unfathomable distance away, that the people, that humans, had settled it via generation ships and that the separation between this place, where they have spread out now into a rich network of worlds, their relationship to Earth is that for them, Earth is the mythic celestial empire. And their understanding…and because the archives that came on the ships, this isn’t really a spoiler, it’s referenced, people reference it, kind of, in the story, but it’s never explained because they wouldn’t think to explain it. So, all the archives that came with the ships were contaminated and broken down.

So, it’s basically, when we look at ancient Sumeria or when we look at the Harapan civilizations of the Indus Valley of four, five, six thousand years ago, we have fragments, and we try to build an understanding of their past by looking at these fragments and by filtering them through our understanding. And that was the core worldbuilding principle I chose to use, which is they have fragments of the past, but they don’t even know Earth is…they wouldn’t even call Earth, Earth. They call it the Celestial Empire, you know, the world…so, they have fragments of it, and how they put that together into their own society is the way…is the foundation on which I built the world. And I did it partly for the Easter eggs, partly so I could use familiar names and not have to use made-up names. And then, it just allows me to play a lot…both with expectations, it allows me to make references that the reader will get, but that the people in the world don’t know is a reference to that thing. It just allows me…it allowed me a lot of leeway to make commentary and also to have fun. And I think space opera should be fun.

I agree. Did you then…doing all this worldbuilding, at what point does the actual plotting come in? Do you work out a detailed plot, or do you write and then use the revision to pull everything together?

Well, again, this story is a little different because it comes with a plot. And it’s not that I use that plot exactly. But I drew heavily, heavily from the actual history of Alexander the Great. And I changed things up and moved stuff around, and that’s ongoing as I work on the subsequent books, right?

But, for example, and this, again, isn’t really a spoiler, the plot kind of works outward. Like, the first scene I specifically had in mind that I knew I wanted to use is a famous incident from the life of Alexander when he was…he would have been, I guess, at this point, 20…his father, Philip—Philip had like, I don’t know, six, seven wives. Not—and in those days, the king would marry for alliances, alliance purposes, and so you could, you would have more than one wife at once, it just wasn’t the same concept of what marriage was for—but his father, having…Philip was actually an amazing character who accomplished an incredible amount, which I won’t go into here, but he kind of had a festival celebrating himself. He was not a man of small ego. He had a festival celebrating himself, at which he also married Alexander’s full sister—so Alexander had one full sister, Cleopatra—he married Cleopatra to…their mother, Alexander and Cleopatra’s mother, was the famous Olympias. She had two children by Philip. Her brother was king of Epirus, which was a neighboring kingdom. And that’s…you used alliances to link those things…so, Philip had a festival to celebrate himself and to marry his daughter, Cleopatra, to her uncle. Because that’s what you did in those days and…

No, I’m wrong. Never mind. OK. Sorry, that’s a different episode. Let me step back. Let me step back a moment. I’m still with the banquet. No, it’s because what I’m writing right now has me in that headspace. This is, see, this is the difficulty of writing history.

OK, when Alexander was 18, move back two years…I knew I was on the right road when I talked about the six wives. Anyway, Phillip had married all these women for alliance purposes, and now he’s in his mid-forties or late forties, and he marries a young Macedonian—oh, and all the wives he had married were not Macedonian. They were Illyrian. They were Epirote, like Olympias. They were…I think there was one from Thalassia. I don’t know. Anyway. So, but they were alliance marriages, right? And now he’s older, and he decides to…evidently he actually fell in love with this young, probably 18, 17, 18-year-old, young Macedonian woman who was highborn and whose uncle was one of Philip’s companions, one of his intimate friends who were his supporters and the people he trusted most, right? So, this man was her guardian. And he, Philip, decided to marry her to, to marry Cleopatra, which angered Alexander’s mother, because, you know, there’s always more rivals, right? Especially if there’s someone in court who can be pushing for this woman. And Philip is still young at this point, mid-forties was still, he wasn’t an old man, he was still young. There was no reason to think he could live easily another twenty years as long as he didn’t die in battle or whatever, right?

So, at the banquet, which Olympias did not attend because of the insult to her, even though she was the fourth of six wives, at the banquet, everyone got drunk. And there were no women at the banquet, I should say. Besides the fact Olympias wasn’t at the palace, there were no women at these banquets. Everyone gets drunk, and the uncle of the new bride stands up. So, remember, Alexander’s mother is Epirote. So, she’s not Macedonian. She’s Epirote, from the neighboring kingdom.

The uncle of the bride, the young bride, stands up and toasts her and says, “Now, at last, we can have a true Macedonian heir.” Right? Well, Alexander was quick to take offense to this. He was drunk and he was eighteen. He jumps up, and he threw a cup at this man, right? And hit him in the head, which, of course, is a horrible, horrible insult in guest terms since Philip was hosting the party. So, Philip, who was also drunk, jumps up and he’s like…I won’t use bad words…anyway, he uses the equivalent of an “eff you, you!” to his own son, right? Grabs a spear and makes to throw the spear at his own son, who has already proven himself in battle at this point, by the way, as a competent war leader. But he trips and falls, and it all goes…and then Alexander says something like, “Well, look, there’s the man who says he’s going to conquer Asia. He can’t even stand upright, you know, because he’s so drunk.” So, then Alexander leaves court for a while, while things cool off, you know. But, of course… and then, the new wife gives birth to a girl baby. So, Alexander comes back, right? So, we’re all good, right. Anyway, that scene is so great on so many levels. That’s the scene, like, that I built the book out from.

What does your actual writing process look like? Are you…I think you’ve said somewhere that you think you’re a fairly slow writer? Do you write with parchment under a tree somewhere or do you go out, do you write in your own office? How do you like to work?

Oh, I write in my own office. I’m fortunate. A back…I know this happened…this was like, a thousand years ago, I also would sometimes go to, like, the library or to the coffee shop to work for a change of scene.

I work in coffee shops. Well, not right now, but I work in the coffee shops some myself.

Sometimes I just want the change, you know, to kind of shake things up a bit. I have a book that I mostly wrote at the library because I found that if I was at home, I wasn’t working on it. But if I went to the library—and this was back when the library, it was hard, it was so hard to get on the Internet at the library, or maybe there were only, like, two limited slots, I think it was before wi-fi, that it was really great or before this whole library had…yeah. So, I was like, I had nothing to do but write there. But yeah, I work at home.

Do you work sequentially, just start the beginning and write to the end of the story, or do you do it scenes and then stitch them together later? How does that work for you?

I am a sequential writer. I know people who stitch, which I find fascinating. It’s not something I can do.

Me, either. So, I always ask.

No, but I know people who do it, who will, like, write out of order. Katherine Kerr, for example, who wrote the Deverry series. She writes scenes…well, you should ask her, but she just had a book out in February called Sword of Fire, a standalone Deverry novel, in fact.

She’d be a good guest. I should definitely reach out.

She would. She would be she’d be a great guest. But, yeah, I tend to…I both outline and don’t outline, so I’m kind of a major-points outliner. I need to know where my endpoint is. I know some of the major scenes along the way. And then…but then I discover. So, it’s kind of like islands, the Hawaiian Islands, for example. So, I can see the point I want to get to, but I’ve got to go underwater to get there. And underwater is the stuff I don’t quite know. But I’ve also…I said before that I’m an athlete. One of the interesting things to me about writing is, I’ve heard of people who can plot everything in their head before they start writing. But I have to…like, literally physically for me, I swear, the act of going from my head through my arms, through my hands onto that motion. I think that’s part of the process for me.

Yeah, I’m not much of an athlete, but I feel that myself as well. There’s something about the actual process of typing that makes it happen.

Yeah. There’s a kinesthetic thing there. And I feel like, if it doesn’t go through my hands, I’m losing a step.

And I have talked to, well, David Weber, for example, because of an accident, dictates most of his work. And I have done that once for a nonfiction book. And it wasn’t too bad for nonfiction, but I’m not sure, I don’t know what would come out if I tried to dictate a story. I may try it sometime just to see what happens.

I know Kevin Anderson dictates his first drafts, I believe.

Because to me, it seems like it’s just such a completely different way of translating what’s in your head into words than the typing process. So, anyway…

Yeah, yeah, yeah,

Everybody does it different, as we said. And that brings us around to the revision process. Once you have that draft…and I know you’ve written extensively about this on your website, so I should point people to that, that you have a three-part, the revision process in three parts on your website, which goes, I think it’s about eleven pages when I printed it out. But, in brief, what’s your revision process look like?

Well, one of the things that happens to me is, when I say I write sequentially, I do, but I don’t. Often, I will write forward to a certain point, and then I’ll say, “Ooh, wait, now I’ve moved myself off onto this other path. I need to go back and fix some of the things that were pointing me to a different path,” because I somehow just can’t, I can’t keep going till the end if stuff is pointing the wrong direction. So, I revise…it’s not that I…I try to write straight through to get a complete draft because I can’t really understand the book until I have a complete draft. But at the same time, often there’s a couple of pause points where I’ll often stop and go back and revise forward and then go on.

But my revision process has a lot to do with structure. I need my books to be structured, like, the framework needs to be right. So, the first thing I always do is, look, “Do these scenes lead to each other? Have I set up the…not the mystery, but I have set up like the character journey or the plot way that I’m presenting?” Like, I might be presenting ideas that and foreshadowing and set up, so that, you know, at three-quarters of the way through the book, the reader will suddenly go, “Oh, my gosh, these two people are going to meet, aren’t they?” Right? And so, that’s kind of my first thing, is to see, “Are these things set up the right way for the ending I want.” Once I’ve done that—and sometimes revising the structural aspects can be a major, major task. My novel Black Wolves, I must have restructured it three times before I settled on the structure that I wanted.

Then I’ll go back…and I would call that a structural revision…then I would go back and do large scene revisions, where I have to ask myself, “Does this scene even need to be here? What do I need this scene to do? Is it helping? Is it helping the larger story? Is it pointed the right way? Are they saying the things they need to say to get me…and, does it lead into the next scene? Maybe I need to flip two chapters because they make more sense.” So, that’s kind of that level. So, it’s kind of like the big level, the broad camera level, the widescreen level, and then the kind of the medium-screen level.

And then, after I’ve done that revision, then I’ll go in and kind of fine-tune the scenes, you know, “Can I cut out any of this dialogue? Can I collapse these two sentences into one? Can I cut out some details that I don’t need? What’s the one detail I need for this scene to pop out?”, you know.

And then the last revision stage for me would be what I would call line edit, where I would just go through and close read it, to cut what I can and to make sure that the language is good and the sentences make sense and, you know, are most felicitous to read.

I think you’ve said in something that I read that you do use beta readers. Where do you find those people, and what do they do for you?

Well…the beta readers I use are just, they’re really just other writers I know. So, I don’t, like, go looking for them. I just build…as I have built community, I have people who will beta read for me. Does that make sense?

Yeah.

And another thing that happens is that you may go through a phase where, like, I’ll have, like, you know, I might have one series that one person beta read a lot of it, but then, the next series they were doing stuff and couldn’t read it and so they haven’t read anything of some other series. So, sometimes it’s just…I go through phases where one person might do a lot of beta reading for me for a couple-of-years period and then maybe none after that, or, you know. So, it comes and goes, what people have time for. I’m the same. I’ve beta read for people as well and, you know. Like, right now, there’s a couple of people who I’ve done a fair bit of reading for. And in ten years, maybe I won’t have, you know, I mean, I just don’t know. It’s just kind of cyclical.

What do you find as a benefit of having beta readers?

The benefit of just, different eyes. They’re looking at it in a way I’m not. And one of the important things about beta readers…it’s useful to have what I call alpha readers, and those are people who just pat you on the back? Sometimes you just need someone to say, “Hey, this is great. Hey, can I have something more? Hey, I love this. Hey, keep writing!” if you maybe are struggling or aren’t sure. But a beta reader is supposed to be there to say, “Hey, I didn’t understand this.” I just read a science fiction novel, beta-read it, and I said, “I don’t understand how this spaceship is laid out. And a lot of the story, the story has a kind of a mystery-thriller aspect. And so, they would say, “Well, I went down to the X,” and I’m like, “I have no idea where the X is.” So, they ended up just dropping in early in. There’s this, like, three-sentence description, and it’s done in a way that the main character is talking about it or thinking about it, where it just lays out how the ship works, how the ship is laid out physically, in very clear terms. Because to the writer, he knew it in his head. He could see it. And he thought that his two words using, I think he used cylinder and torus, well, that should be enough. Right? And I’m like, “I don’t understand where I am.”

That’s actually something I often mention when I work with new writers is yes, you understand everything that’s going on. It’s all very clear in your head, but you have to put enough on the page for the reader to be able to make that jump and get some sense. Yeah, that’s a…it’s a common thing.

But I still struggle with that all the time. Every book.

Yeah, me too.

I mean, do we ever get this fully right?

And this is something…we’re getting up to the editor stage now, where you send it in, and the editor takes a look at it. That’s often something that I’ve found that the editor will come back and say, “You didn’t explain enough of this, or there’s a connection here that’s missing or something.” Do you get that same kind of feedback?

Well, that’s what a good editor does, right? So, there’s for me, a…I’m going to say, bad editor. I hate using that word bad…a bad editor wants you to write the story that they think it should be. A good editor says, “What’s the story you want to tell here? And how can we make sure that you’ve told that in the clearest, most engaging and most accessible way possible?” Accessible based on what your goal is. I mean, if your goal is to write a very dense inaccessible tome, that’s fine. I mean, seriously, that’s fine. But you want it to be that. So, a good editor will look at what you’re doing, and they’ll be able to get what you’re doing, and they’ll be able to dig into you and say, “Is this what you want? What are you trying to get here? How can you bring this out more clearly?”

And we mentioned that we both worked with Sheila Gilbert at DAW.

Yeah.

And one of the things I’d like to point out about editors, and Sheila is a great example, is they have seen so much. So many stories and so many ways of telling stories. They’ve seen all the mistakes and they….yeah. And I always really appreciate the feedback I get from Sheila for that reason.

Well, and the other thing about an experienced editor is that an experienced editor is patient for that reason, because they love books. They wouldn’t be doing this if they didn’t love books. And they’re patient with your flaws. So, sometimes…some people will go over and over and over a book because they want to turn in something that could be immediately typeset. And sometimes it’s because they don’t want other people, other hands in it, which is fine, I mean, we all get to process how we do that. And others, I think it’s because they’re uncomfortable with people reading something flawed. But I’m a youngest child. I do not care. I want to ultimately write, I ultimately want published, the best book I can. And so, I’m happy for my editor to see it at a little earlier stage if that means that she can help me with some of the places that I might not be seeing, you know, and then that allows me to to get my fingers in there at an earlier stage when the narrative is more elastic, because I find for me that as I do each stage of revision, you know, down to the line edit, by the time at the line edit stage, things are less elastic now, I can’t make big changes without having to rip apart the whole book. But I can make larger changes earlier on. It’s not solidified yet. So, I would, you know, I would rather…I like getting feedback at that earlier stage and then in the other stages as well.

Well, we are kind of at the end of the time here. So, I do want to ask you…you kind of touched on part of what I usually ask at this point, why people create and write. You mentioned that right off the top. But to bring it down to you…and this is sort of in the bio, breathing and writing, right? Why do you write? Why do you do this? What do you get out of it, and what do you hope that your readers get out of what you present to them?

It’s a particularly interesting question, because what I…I still get out of it what I got out when I was young, which is just the joy of telling stories and kind of the amazement of telling stories about people who don’t exist, you know, doing things that never happened. Why do we enjoy these things? It’s kind of bizarre when you think about it, but it’s also really cool. So, I still have that. But then, as you spend decades doing it, as I have, and as you have, right, then other things happen.

I mean, partly for me, it’s like, I have no other skill at this point. You know, it’s like this is my marketable skill. This is what I know how to do. I have a habit. I’m used to doing this. But the other reason is that I just want to do, I want to keep getting better. So, part of it for me is just that I want to write, I want to do better with my next book. I want to do something that I couldn’t do ten books ago, but now I can do it. Now, I know, because for me the process is just this, the excitement of challenging myself. So, I can continually challenge myself at something that I like to think I have gained skill at, that I am no longer an apprentice, but a master at doing. And I just love that sense of challenge and of getting closer to, you know, having that product and…not product, but that story at the end where I say, “Yes, yes, this was it. This was what I wanted to write. This matches more closely than ever before that thing I had in my head.”

I’ve sometimes used the metaphor of writing is, when you first have the idea and the concept, it’s like this beautiful Christmas tree ornament, and it’s shiny and it’s perfect, and then you smash it, and you try to glue it back together with words.

That’s great. Yeah.

And what are you working…oh, the other part of that there was, what do you hope your readers get from your writing?

Well, you know, I hope that they feel immersed in the world and that it gives them that…I hope that while they’re reading it, they really feel that they are in that other place, you know, living with these people through whatever they’re going through. That’s really my goal as a writer, is that immersion.

So, you’re offering them that portal that you never found when you were a kid?

That’s right. That’s right, Ed.

And what are you working on now? I mean, obviously, the next book in this series, but…

Yeah. Yeah, I am.

Does it have a title?

Yes. Book two is called Furious Heaven.

And anything else in the works?

Yes, but nothing I can talk about at the moment.

OK. And where can people find you online?

I am on Twitter @Kate ElliottSFF. That’s Sam Frank Frank. On Twitter. Did I say that, Twitter, already? And I do have a website called I Make Up Worlds, which I haven’t been posting on recently. So mostly it’s Twitter these days for me. I’ve backed off on other things. It’s just too much.

Yes. So often, social media seems like too much.

Yeah. Yeah. And I…yeah. And I’ll be backing off online quite a bit for the rest of the year to just really focus on writing.

All right. Well, thank you so much for being a guest on The Worldshapers. I really enjoyed the chat. I hope you did too.

I did, Ed. And I’m sorry I went so history geeky. I just can’t…I just love history. And I want to say one last thing about worldshaping and about worldbuilding and how much I recommend to people that they read widely about human culture and human experience. I think that is really the best foundation any of us can have as writers.

An excellent recommendation. OK, well, thanks so much.

Thank you.