Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

An hour-long conversation with Walter Jon Williams, Nebula Award-winning, New York Times-bestselling author of more than forty books of historical fiction, fantasy, and science fiction, as well as work in film, television, comics, and games.

Website

www.walterjonwilliams.net

Walter Jon Williams’s Amazon Page

The Introduction

Walter Jon Williams is the Nebula Award-winning, New York Times-bestelling author of more than forty volumes of fiction, in addition to works in film, television, comics, and the gaming field.

He began his career writing historical fiction, the sea-adventure series Privateers & Gentlemen, then, when the market for historical novels died, began a new career as a science fiction writer. Since then, he’s written cyberpunk, near-future thrillers, classic space opera, “new” space opera, post-cyberpunk epic fantasy new weird, and the world’s only gothic western science fiction police procedural (Days of Atonement). He’s also a reasonably prolific writer of short fiction, including contributions to George RR Martin’s Wild Cards project.

Williams has been nominated for numerous literary awards, and won Nebula Awards in 205 and 2011. In addition to fiction, he’s written a number of films for Hollywood, although none have yet been made. He’s also maintained a foot in the gaming industry, having written RPGs based on his Privateers & Gentlemen series and his novel Hardwired, contributed to the alternate-reality game Last Call Poker, and written the dialog for the Electronic Arts game Spore. In 2017, he was the Guest of Honor at the 75th World Science Fiction Convention, held in Helsinki.

In addition to writing, Williams is a world traveler, scuba diver, and a black belt in Kenpo Karate. He lives in New Mexico.

The (Lightly Edited) Transcript

So, Walter, welcome to The Worldshapers.

Happy to be here.

I always try to find connections, and I can think of two. You live in New Mexico, and I was born in New Mexico. So that’s something.

OK.

I was born in Silver City, New Mexico, but yeah, I didn’t live there very long. We moved to Texas, and then we moved from Texas to Canada, which is where I am now. But, yeah. So, there’s that connection.

Silver City is quite pretty and has quite a history.

I don’t believe I’ve ever seen it when I was old enough to remember it. I know we went back a couple of times when I was young, but I don’t have any memories of it, unfortunately.

Well, the thing I like about certain old towns is, you know, if they were, say, a mining town, silver-mining town, which Silver City was, and then the silver mining went bust, they never had enough money to tear down their old Victorian town and build up an ugly new modern one.

Mm hmm.

So, it’s still got all these beautiful Victorian buildings still, as does all the surrounding area.

It’s a bit like Moose Jaw here in Saskatchewan. They had a couple of fires in the early years that burned everything down. So, they passed a bylaw that everything had to be built out of brick.

Huh. OK.

And then there was kind of a boom and then a bust. And a lot of those old brick buildings are still there. So, Moose Jaw has some really nice character buildings still existing. Plus, it has that name, Moose Jaw, going for it. The other connection is, we did actually eat at the same restaurant at some convention, but I can’t remember which one. I was probably Denver or Reno, but . . .

I think I’ll have to take your word for it. I’ve eaten in many restaurants at many conventions.

Yeah, so have I at this point. You more than me, I’m sure. And they do tend to kind of run together over time. Well, anyway, so, that’s not actually what we’re going to talk about. We’re going to talk about your writing process. But first, I want to take you back into the mists of time, which is getting further and further back for some of us, I guess. For all of us, really. Where did you grow up, and how did you get interested in reading and writing and all that good stuff? How did you get started in this strange way of making a living?

I was born and raised in Duluth, Minnesota, and I always wanted to be a writer. As soon as I knew what a writer was, I wanted to be that. I was probably four years old. I didn’t know how to read or write yet, so I would dictate stories to my parents, who would write them down for me. And then I would illustrate them with my crayons, and fortunately, none of those have survived. And so, I mean, it wasn’t a choice for me. I was compelled to be a writer, and I just work hard at it all my life until I managed to sell some fiction. And then I worked hard at writing more fiction to sell.

If you wanted to be a writer, that must have come from having encountered books. So, was there a reading component to your wanting to become a writer, I presume?

Well, once again, I didn’t know how to read, but I had books read to me and comic books, which I think were a big influence on my very early writing development, since I was better with crayons than I was with, you know, actually crafting prose. So, let’s see. And so, my family left Duluth and moved to New Mexico when I was thirteen. And with some exceptions, I’ve been here ever since.

Did you study writing formally at some point or . . . ?

I took some creative writing classes in college. I’m not sure that they helped. Well, I think, you know, I took a lot of literature courses, and that exposed me to a lot of different material, different writers, different ways of writing, different approaches to writing. And those turned out to be quite valuable. But the actual writing classes . . . well, probably they did no harm.

Well, I often ask writers about that, and more often than not . . . I have rarely gotten a ringing endorsement of creative writing courses at the university level from anybody I’ve talked to you on the podcast. So, that’s interesting. Were there specific books, once you were reading your own books, were there specific books along the way that influenced you, do you think?

Well, science fiction was an early passion. I think I was in second grade when I . . . my mom, who was not a science fiction person at all, sort of marched through the local public library one day, and she knew I would like science fiction, so she grabbed a couple of science fiction books off the shelf and brought them home for me. And the first one was Robert Heinlein’s Have Spaceship Will Travel, which is still my favorite Heinlein novel.

Mine too, actually.

You know, I don’t know why it hasn’t been made into a movie. It would be glorious. But so. I read science fiction from second grade on. I was really fond of books about natural history and animals, including, you know, fiction about animals, you know, The Jungle Book and so on. And then I just continued, and I read a ton of history because I just love history, and that’s a big influence on one of my current projects.

Just mentioning animal books, did you read the Black Stallion books by any chance?

No, I did not. They were not available.

The only reason I ask is, I often ask if anybody has encountered them because it’s perhaps little known that Walter Farley wrote a subsection of those, the Island Stallion books, that were actually science fiction. There’s, like, aliens involved, with horse racing as well.

If I’d known that, I would have sought them out, I’m sure.

His final book that he wrote, late in life, Alec and the Black are wandering around the southwestern desert, Arizona, I think, not New Mexico, while there’s been some sort of asteroid strike or something, it’s like a post-apocalyptic almost setting, with the horse and the boy. And it’s very odd, really. So, that’s why I asked.

Yeah, it’s . . . you sort of wonder if he was running out of ideas for ordinary horse stories, you know that., OK, well, let’s have a post-Holocaust horse story and see what that seems like.

It might have been something like that, or he was just feeling really depressed. I don’t know. It kind of reads that way, too. So, you mentioned the historical, and when you did start becoming published, I know that your first books were historical novels, were they not?

My first published books were. There were some unpublished ones that weren’t. There are a whole host of projects that I never completed for one reason or another, including science fiction and fantasy. I wrote a sort of literary novel that took place in the Civil War that attracted some attention but never got published. And I followed that up with a murder mystery and then had the idea for a series of sea-adventure novels. And those were the ones that sold. It was . . . they were in the realm of C.S. Forester or Jack Aubrey, you know, except that my heroes were Americans rather than Royal Navy.

Did you have any . . . I’ve always had a fondness for these stories, one of the books, one of the series I read growing up was a series of British children’s books called Swallows and Amazons, in which the kids sail. Now, they’re not. They’re just sailing, like, little sailing dinghies around the Lake District in England for many of the books. But in their mind, they’re having these sea adventures with pirates and broadsides and all that stuff going on. And I think that’s where my interest in and see stories came. Did you have any connection to the sea other than just wanting to write about it?

Well, I think growing up on Lake Superior. Lake Superior is, you know, it’s the largest body of fresh water on the planet. And it is, it’s, you know, it’s pretty much a sea of its own. And also, growing up in Minnesota, the land of 10,000 lakes, I spent a lot of time in the water when I was a kid and on boats. So, you know, I grew up, and I became a small-boat sailor and a scuba diver. So, you know, it’s been a consistent thing in my life.

And that series you’ve brought out as ebooks now, haven’t you? After they were not available for a while. It’s called Privateers and Gentleman, right?

That’s the series title. And I also restored my original titles that the publisher . . . the original publisher was Dell, and they had a formula for how they wanted series books to be titled. Which was The (Adjective). And the adjective would change, but it had to be a two-word title, the first word had to be “the.”

That gets repetitious after a while, I would think.

Yeah, yeah. And especially as I had much better titles. Those titles are now restored to the books that needed them.

Where could people get those if they wanted to read them?

Your favorite online bookstore.

Available everywhere.

Available everywhere I can find to put it, yeah.

So how did you make the switch from the historicals to science fiction?

Oh, that was easy. The market for historical fiction in the United States completely collapsed about May of 1982. And so, what I planned as a ten-book series became a five-book series. And so, I spent a desperate six months writing proposals for things that didn’t sell. And it was across the spectrum, I mean, I wrote proposals for mysteries, for historicals, for science–not for science fiction, actually—everything but category romance, I think. And none of them sold.

And then, a science fiction proposal that I had written some years before sold. And so, I became a science fiction writer. And the science fiction proposal had been bouncing around publisher to publisher without being read. It’s kind of a fascinating saga, it’s probably too long for this interview, but it sort of explains how publishers can screw up repeatedly. And it finally ended up at Tor books. And the editor at that point was Jim Baen. And there were only three people in the office. There was Tom Doherty, who was the publisher, Jim Baen, the editor, and then there was Mrs. Doherty, who ran the account—was the accounting department. And, you know, now Tor is the largest science fiction publisher, and it doesn’t run like that anymore. But Jim Baen read the proposal and bought it. And although it had been on the market for two or three years, it actually sold to the first editor who rented.

How did it not get read at the other places that it had been?

Well, there were a lot of mergers going on in publishing, as there are now. And so, you know, I don’t recall the exact sequence, but, you know, it was sent to Ace. And Susan Allison, who was the editor, left Ace to go to Berkeley, and until she was replaced, they put a buying hold. So, then it came back, and then it was sent to Berkeley and to Susan Allison at Berkeley, and then Berkeley acquired Ace and suddenly they had too many manuscripts sitting in the office. So, another buying hold went, and then it went to David Hartwell at Timescape, and it was lost in the mailroom for about six months. And by the time that was discovered, they had put a buying hold on. And so, it just kept bouncing off of these things until it actually went to an editor who still had a publishing schedule to fill up.

That must have been satisfying when it did finally sell.

I was greatly, greatly relieved because I was, you know, beginning to look in the help wanted section of the paper so that I could make my rent. And suddenly . . . although it has to be said that the science fiction sold for a lot less money than the historical fiction did. So, I was . . . it took me a few years before I could reach my former miserable standard of living from where I was merely poor instead of in wretched poverty.

Yeah. I can relate. So, there was also a venture into writing for games, and you’ve written for . . . I know, I’ve been a full-time freelancer for thirty years, and I know you do, you know, anything for a buck, basically, but how did you get involved on the gaming side, and have you kept your hand in there?

I’d always been doing games, I’d been playing games for a long time, Avalon Hill games and spy games, historical war games and stuff and Dungeons and Dragons. And so, you know, I was familiar with the genre. And what happened was Jim Bain formed his own publishing company. He left Tor, formed Baen Books, and he also decided to get into computer games, which was a new thing. And because he had a distribution deal with Simon and Schuster, he was going to market his computer games through Simon and Schuster, and they would appear in every bookstore in America and be a huge success. Except, he didn’t realize that the crack Simon and Schuster sales force weren’t interested in computer games, didn’t know how to sell them, and didn’t care to try. And so, it ended up being a terrible failure. And I did write four computer games for Baen Software, of which only one saw print, and the company collapsed before the others could appear.

I’m curious about it because it’s, you know, I’ve never done it, and I’ve always thought it might be interesting to do. Playing them, it seems to me like there’s an . . . there’s an awful lot of dialogue that has to be written for every conceivable iteration of how the game might play. Is that a fair description of it?

Well, especially with, say, a large-scale computer game. I did write the dialogue for a game called Spore, which was sort of galactic adventure with many different alien races that fit various categories of every warlike or mercenary or capitalistic or concerned about ecosystems or whatever. And so, you know, when you say hello to one of them, depending on what kind of alien they are, which category they fit into, they will respond in character. And you end up having these long dialogues with these people. And it was done very imaginatively. They found all these artists who could do gibberish. And so, you know, you would say, “hello,” and this gibberish would come back at you along with the translation. And that was quite epic, but fortunately, I was paid quite well for it. You know, it’s incredibly tedious, mind-numbing work. And I was the second writer they hired. The first one had, I think, OD’d on it and gone kind of nuts, and so they wanted someone who could rein it in a little more.

You didn’t have to write the gibberish; the voice actors made that up?

The voice actors. Yeah.

You’ve also done some screenwriting, haven’t you?

I have. I wrote several movies that never got made, which is a typical screenwriter experience. I should point out that ninety-nine percent of scripts never get made. But I got paid for writing. The only thing you can see of mine is a science fiction show called Andromeda. And I had one episode in the first season, and it was . . . there were just epic casting problems on that particular episode. And so, it was rewritten, I think, twenty-seven times in the ten days that it took to shoot, when they realized that their guest star couldn’t act and couldn’t remember lines.

The fellow I interviewed for the last episode of this podcast, Chris Humphreys, is both a writer and actor, and he actually played a starfleet commander on Andromeda at some point, but hopefully not in that episode.

No, there weren’t any starfleet commanders in that episode.

All right. Well, let’s talk about your novels then. That does kind of tie in because I’m curious, whenever I talk to somebody who’s done screenwriting or other forms of writing like that, do you learn something doing that that you then bring to your novels? Or was it the other way around? Was the fact that you a novelist, you know. . .?

I was an established writer by the time I did any of these screenplays. So, I already knew how to write fiction. But the main thing was a kind of mental switch because, in my fiction, my characters all have strong inner lives. And they’re always thinking and reacting and having emotional responses to what’s going on, but it’s not necessarily visible to any of the other characters. And so . . . but you can’t have that in a screenplay. You can’t have somebody think in a screenplay and not tell you what he’s thinking. All the audience sees is action and dialogue, and so, I had to make that adjustment. My characters couldn’t have interior lives. It was only outer life.

Well, I do some stage acting, and I’ve written plays, and it’s much the same thing. Everything is driven by the visible action and the dialogue and whatever the actor can do to emote. But, you know, everybody interprets that differently, depending on who the person is that’s viewing it.

Yeah. You know, I did have, you know, second readers on my screenplays and stuff. And they would ask, I don’t understand why your character is doing this. And I said, “Well, because he worked it out in his head that this is what he should do and then . . . No. That’s not a viable approach for screenwriting.

There’s the few where they have a voiceover narration, but that always seems a little forced after a while.

I really miss the artist’s soliloquy. I wish I was living in Shakespearean times so that I could just have the character turn to the audience and explain what he was going to do.

If you ever get a chance, there’s a show on Amazon Prime now, it’s from the BBC, called Upstart Crow, which is a situation comedy about Shakespeare writing his plays.

It is terrific. I’ve seen all seasons.

I thought of that because the actors will turn to the front and say, “By strict convention. I can now say what I want to say, and nobody around me can hear what I’m . . .”

Yes.

Well, let’s talk about your writing of novels then. Now, Fleet Elements, that’s the most recent one—well, you have a new short story collection we’ll mention as well, later on. So, using that as an example, we’ll talk about how you write your novels. And I guess the first thing would be a bit of a synopsis without giving away anything you don’t want to go away.

OK. Well, my elevator pitch is war and revolution as seen through the eyes of a pair of star-crossed lovers. Or alternatively, star-crossed lovers experience war and revolution, but it is set in the far future in a somewhat decrepit space empire in which humanity and several other alien species were conquered by another race. And that other race is gone now. They all died. And now, we, the human race, and these other species have to figure out what comes next. Because they’re very good at taking instruction from these totalitarian aliens, but the totalitarian aliens aren’t giving them instructions anymore, and now, they have to work it out on their own, and they’re not used to that, and they’re not very good at.

I should point out this was inspired by–I was reading a lot of classical history, Polybius and Livy and people like that, and they told this wide-scale history with very vivid characters. And I thought, I should be able to do that. And so, when I planned this series, twenty years ago now, I planned it for nine to twelve volumes. And for various reasons . . . anyway, the fifth or seventh one has just come out, depending on how you point them there. This is the fifth one from Harper Collins, but there was one from Tor, that was a novella, and there was another novella that I published on my own. So, I think of this, Fleet Elements, as book seven, but the publisher thinks of it as Book Five.

Do you know exactly how many volumes it’s going to be now, or is it still in flux?

I think twelve.

So not even halfway yet, depending on how you count.

I’ve plotted them all out. I know what’s going to happen in all of them. That’s part of my process. In the first trilogy, I knew what the last line of the last book was going to be before I wrote the first line of the first book. I always have the end in view, and I always know where I’m going. Sometimes there’s a certain amount of difficulty in getting there. I always know the beginning of the book really well, and I know the end of the book really well, but the middle part is sometimes a bit of a mystery. And that’s where I tend to struggle.

Well, you mentioned what the inspiration was. Was that typical of the way ideas . . . I mean, ideas come from everywhere, I know, and it’s cliche to ask, where do you get your ideas? But is that fairly typical for you, something you’ve read or just something you’re thinking about, or how does it work for you?

Very often, I get an idea just from reading other people’s fiction. And I see something that was undeveloped or something that could be viewed in some other way, and usually, you know, even my short fiction, there’s more than one idea happening. So, I tend to like the collision of ideas, so I’ll wait till I get a certain number of ideas that are kind of undeveloped, and then I will sort of have them smash each other head-on like particles in a particle beam accelerator just to see what happens.

See what kind of strange quarks emerge.

Yeah.

You mentioned a little bit about knowing the beginning and the end, but are you much of an outliner? I mean, this is a big sprawling series.

Yeah.

How much work did you do ahead of time to plan it out? What does it look like for you? Is it very detailed or more sketchy or what?

When I’m working on one project, I’m always thinking about other projects. So, I was able to plot out twelve volumes while I was writing something else. Because that’s just usually how it works, you know. I’m not a very fast writer. I’m a plodder, but I’m persistent. I don’t . . . you know, I write every day. I just don’t write a huge amount of words every day. And so, you know, I have a lot of time to think about my next project. And I have probably outlined, at least in my head, more projects than I can write in a lifetime.

What does the actual outline that’s not in your head look like?

Well, there are a couple of kinds. I mean, I have to write a synopsis for the publisher, right? Because publishers require synopsis and sample chapters even for writers that they know well now. I mean, I recently, you know, sent a proposal to an editor I knew well, right, and he said, look, the company requires me to have sample chapters. I know you can write. I know you don’t need to write these sample chapters; you don’t have to prove anything to me. But the company has this checklist, and I have to put that check there. And so, I wrote him those damn sample chapters, you know, really annoying.

I don’t have to do that with DAW. Still just getting by with the synopsis.

Well, that’s because DAW is still family owned.

Yeah, I think that’s the difference.

They aren’t owned by an international corporation. Good for them.

So, your synopsis, will it be like ten single-spaced pages or . . . ?

Yeah, something like that? Well, you know, it worked out to ten double-spaced pages. But I write outlines for myself, and they are a lot more eccentric. I tend to write them on yellow legal pads in colored ink with different characters being represented by a different colored ink and arrows and timelines and stuff like that. It would be incomprehensible to anyone else. I know what all this stuff means, all these weird scribbles, but I can’t see anyone else getting a hold of one of those outlines and being able to write a book from it.

How closely do you follow your outlines once you actually start the writing process? Do you find that you wander off as you create things along the way, or are you fairly strict?

Well, outlines are just outlines, and I don’t so much wander away from the outlines as I find other aspects of the story that would contribute to the value of the fiction, right, so, you know, I find new sidelights on characters, new sidelights on the action. And so, for me, it’s a process of addition. I start with the outline, and then I add things as I go if I think they would contribute.

And what about your characters? Do you do a lot of detailed work on them beforehand, or do you discover them as you write?

Uh, I pretty much . . . the major characters I know pretty well by the time I start. I don’t always write down their personalities or the little details and stuff, but I have that worked out in my head.

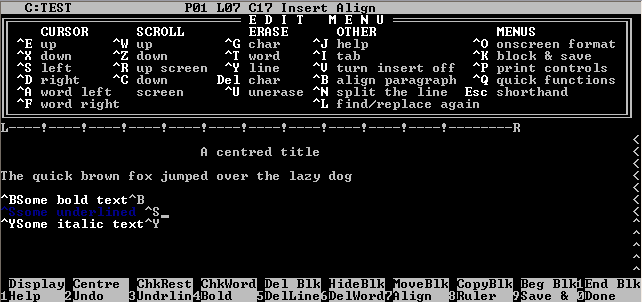

You mentioned that you write every day. What does your actual writing process look like? You outline on yellow legal paper, but I bet you don’t write on yellow legal paper longhand.

No, no, I write on a computer. I use Scrivener, which is a software that is developed specifically for writing fiction.

Yeah, I have it, and I’ve never climbed the learning curve to use it. I’m still plugging away on Word.

Well, the thing is that, as with every modern word processing program, most of it is stuff you’ll never use.

It’s certainly true of Word.

Yeah. That’s true of Scrivener, too. There’s just a lot of stuff in there that you probably won’t ever use. But it does have a very useful outlining function where it actually gives you the index cards and the little pins. And you could put them in and rearrange them and stuff. It allows you to rearrange scenes very easily, which is extremely useful in at least some of my projects where I’m not too sure on the chronology until it’s all done.

Yeah, I should probably . . . the one I’m working on now is a space opera called The Tangled Stars, and it’s kind of tangled my brain, too, so I should probably be using Scrivener. That might help. So, you said you’re not a fast writer. Do you have a set word counts you try to get done every day or . . .?

I seem to average about 500 words a day. It’s not a lot, but I get to write one book a year plus some short fiction, and that’s what it amounts to.

And once you have your first draft, how does the revision process start for you? Or do you write in drafts? Do you do a rolling revision or what?

I don’t anymore because word processors make it so easy to revise. So, probably by that, by the time I’m done with my, quote, first draft, unquote, everything’s been gone over half a dozen times. I always start my day by revising the previous day’s work. And, you know, whenever I have to go back and look something up, I’ll probably revise it a bit. So, ideally, it’s very polished by the time I get to the end of the first draft. So, revision for the second draft is generally pretty quick and easy just because I’ve been over it so many times.

That’s interesting because the very first person I interviewed on here was John Scalzi, and he was talking about how he does rolling revisions. But then I’ve talked to other people who started on typewriters, as I’m sure you did, because I did, and you’re maybe a little bit older than me, I’m not sure, but somewhere along in there. And he thought that people who wrote on typewriters tended to still do single drafts and then go back to the beginning and revise it, as you had to do on a typewritten manuscript.

Pretty much.

But it sounds like you’ve switched more to the word processing.

I’m very pleased that I never have to use a carbon ever again.

Yeah.

But yeah, and since I’ve adopted a word processor as opposed to a typewriter, my books have gotten a lot more complex simply because the word processor makes that easy to do. The stuff I wrote on typewriters was very straightforward.

I still remember the first decent printer I had, because of course, dot matrix printers, editors didn’t want that. I had a daisy wheel printer, but I had to feed the paper into it just like it was a typewriter. I wasn’t typing it, but I still had to sit there, and it would make a carpet. So, I was still using carbon paper and feeding it into my daisy wheel printer. I don’t miss that. Yeah, I’m old. So, do you use beta readers or anything like that? A lot of people do.

Well, I use my wife, who was a very good beta reader and who has worked as a copyeditor in the past. So, I get a free copyedit, which is pretty cool. But I used to belong to several workshops, and I would workshop everything. And then, I started a workshop of my own called Taos Toolbox, where I actually teach writing for two weeks up in a ski lodge in northern New Mexico every summer.

Oh, nice.

And I work with Nancy Kress, who is just brilliant at teaching.

That’s where I heard that, because I interviewed Nancy and I think she mentioned it.

But it kind of ruined me for workshopping because, during that two weeks, I have to read and critique maybe three hundred and fifty thousand words of fiction. And I am so burnt out by that process that it takes me a year to recover. And I just don’t want to workshop anymore. I don’t want to have to read anybody else’s drafts until it’s time to do Taos Toolbox again.

Do you . . . I’ve done a smidgen of teaching, and I’ve been a writer in residence and worked with a lot of writers at a couple of libraries where I’ve been a writer in residence. Do you find that teaching writing benefits you as a writer?

Not that much. I do occasionally get excited about one of the students and, you know, but it’s mainly—I’m mainly teaching in this, I’m not necessarily out to learn new tricks.

Do you ever find—

That’s it . . . I have I encountered a dilemma in one of my, my current project, and I went back and looked at my own lecture notes. Which I normally don’t do. I looked at my notes, my lecture notes, and I found the solution to the problem I was having. And that was kind of fun. I actually took my own advice.

I was actually going to ask because that’s something I found. You know, I will confidently tell somebody, you know, you should do it like this or something like this, and then, just don’t look in that book I wrote where I didn’t do that. Because it’s easy to give advice sometimes that you don’t take yourself.

Well, writers are very individual, and they each need, you know, critique and so on that is pitched to them. And this is why Nancy and I do so well, because Nancy has a completely different approach to writing than I do. I’m a plotter, she’s a pantser, and so if my approach won’t work for you, here’s her approach,

Well, that’s one of the reasons for this podcast, is why it’s, you know, it’s focused on this kind of stuff, so that people can go and find out that there is no one right way to do this thing. You’ll hear every possible approach from somebody that I’ve interviewed or will interview in the future, I’m sure. So, going back to the revision, are there specific things you find that you have to work on in revision? Like, is there a consistent tick that you have to clean up or anything like that?

Well, my first drafts tend to have very elaborate, long sentences with peculiar syntax and a lot of words derived from Latin roots, polysyllabic words from Latin roots. And so, I have to remind myself to make the syntax a lot more straightforward, replace the Latin words with Anglo-Saxon words, which are punchier. And that’s my typical . . . I mean, if you actually saw a very first draft of mine, you would think I was hopeless. I really do need to spend a lot of time polishing it to make it readable.

But clearly, you get there.

Yeah, I think a lot of it is, English is not my first language. And so, it’s a struggle to translate the language that’s going on in my head into English.

What is your first language?

I don’t know.

Perhaps it’s Latin!

It seems to be a symbolic language. It’s like . . . when I think, it’s like laying out an array of Tarot cards. And so, I have these different symbols that together all means something, but when I translate it, I have to literally do the translation and add the grammar and all of that. I’m the only person I know who has this problem. Most people apparently think in their native language, and I guess I do, too, except it’s not English.

That rings a bell from somebody who was talking about . . . hey were startled to realize that other people didn’t think the way they thought, and I don’t remember who it was, or if it was exactly along those lines. But somebody else had told me something similar to that, which I find . . . I find it fascinating because, you know, one of the things about writing is, we present the illusion that we know how other people think, right, but really, we don’t, we don’t have a clue what goes on inside anybody else’s head.

Well, I know what’s going on in my character’s heads, and that’s kind of all that matters as far as my books go.

Yeah.

I know how they think.

Your readers come to that and will actually take something different than what you’re picturing in your head.

Yeah, you’re right.

Because it is a collaborative effort.

I find that people read the book that they want to read, and it isn’t necessarily the one that I wrote.

So, once you have the book and it goes off to the publisher, what does the editorial process typically look like for you? Are there things that come back, or is it pretty clean . . .?

It’s mostly sitting around for months waiting for my notes. And, you know, I won’t name any names, but I turned in a book last September, and I’m just getting the notes from it today, supposedly.

Well, it will be . . . you know, you’ll be looking at it with a fresh eye, I guess.

So, I’m going to be doing, you know, spend the next week doing a bunch of rewriting, I expect, you know, unless he says, “Oh, it’s OK, we’ll just send it to the copyeditor.”

Are there things that you typically get editorial notes about? Like, in my case, from Sheila Gilbert at DAW, it’s usually, you know, I didn’t explain enough about some aspect or, you know, the characters need a little more development, that sort of thing.

Yeah, uh, generally, I think because I know too much about the way that my characters think, I don’t necessarily explain their motives and actions as clearly as I could. So, it’s always useful to have someone say, “I need to understand why this action is happening now,” and then I can handle that. Another thing I tend to do is I can overdo things. You know, it’s just the prose just becomes too much. And I need somebody to tell me when to back down, back off, and let the story happen instead of scenes of hallucinogenic intensity.

That sounds like you really enjoy the words themselves. Is that fair to say?

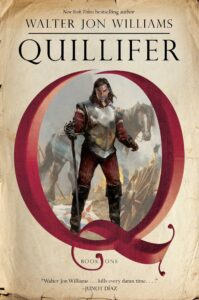

I do. I have a series out now called Quillifer, which is basically my love letter to the English language. I mean, aside from being a jolly good read, you know. But I am deliberately spending a lot of time playing with the language in that series.

I do love a good, convoluted sentence myself, as people have told me, so I can appreciate that. I also wanted to . . . you have written a lot of short stories, and in fact, you have a collection out now, you said. Novellas, mostly, but some short stories.

It’s just out this week. It’s The Best of Walter Jon Williams, oddly enough, out from Subterranean Press. It’s 200,000 words of fiction, which is, you know, a couple of novels worth. Mostly it’s a longer short fiction, novelettes and novellas, and including a lot of award nominees and a few award winners. So, you know, I’m very proud of it. I just wish I could have added another 100,000 words . . .

That’s the sequel!

. . . because there are always some I wish, you know, there was room for.

Of course, if you call the first one The Best of Walter Jon Williams, would you have to call the second one The Second-Best of Walter Jon Williams?

I think Even More Best.

Even More best.

Even More Bester of Walter Jon Williams.

So, these would go back right through your entire career?

Pretty much. Yeah, it’s from the mid-’80s through the fairly recent present. And it’s sort of every stage of my career represented.

So, you write novels and short stories. Do you think you have a preference for one that you’re better at than the others? I always think some people are better at short stories and some people are better at novels. Are you good at both, or . . .?

My best work is in the shorter form because, in something that is of a modest length, everything can be perfect. You can actually put everything in it that you think ought to be there and then make sure it’s available to the reader. For a novel, something the length of a novel, something’s going to go wrong somewhere. There’s going to be a mistake, there’s going to be, you know, some of my tangled syntax got through all the editing. So, you know, I view my novels as good but necessarily flawed, which is how I view everybody’s novels. But my short fiction, I’m very proud of.

I’ve often used the metaphor of where you have this . . . in your head, the story is this beautiful, shiny Christmas ornament, absolutely perfect. And then you smash it with a hammer and try to glue it back together with words. Yeah, that’s the way it feels to me, that initial moment of, “Oh, this is going to be perfect,” and then you can’t actually get to perfect, unfortunately. Well, I’m going to ask the big philosophical questions—I’m going to put reverb on that sometime—you’ve been writing for a long time. You say you always wanted to be a writer, but the first one is why? Why do you write?

Well, it remains a mystery. It was a compulsion. It was an irresistible compulsion to be a writer. And that irresistible compulsion lasted from when I was four years old to when I was around forty, when it began to fade. And so then, I realized I was no longer compelled to do this, but it was kind of the only thing I was good at. You know, it’s not like I have a work history. My last real job was, like, in 1978, and so, I have no job history. I’m not even qualified to be a greeter at Wal-Mart, in terms of the straight world. So, but what I realized I had to do was I had to find some reason to love what I was doing and to really love the craft and love everything I was working on and find joy and delight in it. That wasn’t necessary before. I didn’t have to love it. All I had to do was just write it because I was compelled to do that. So, I think my approach to writing now comes from love, and this is what I tell my students. “If you don’t love it, don’t do it.”

Don’t do it for the money.

Yeah, because there won’t be any. Sorry.

So, you say you found a love for it. Why do you love it now? What do you love about this?

Why do you ask these complicated questions? I . . . it’s just I enjoy doing stuff that I’m good at. And this is the thing that I’m best at, is writing fiction. And I do a lot of other stuff, you know, I’m a scuba diver, I’m a martial artist, and love all that to a certain degree. But that’s not where, you know, my homeworld is. My homeworld is fiction.

Do you find some love in the love that your readers give back to you when they read something of yours and they really enjoy it?

It’s always gratifying when I hear from the readers. But see, the thing is, between the time that I finish a project and the time that it appears in print, I’ve written a bunch more on other projects. So, you know, when a novel comes out, I may have written two novels in the period of time between finishing that one and it appearing in print, so my head is in another place. And once I deliver a book, it’s kind of not mine anymore. It kind of belongs to the reader. So, there is . . . there’s a part there’s a time in which I know I’m the only person that possesses this work. Right when I’m working at it, I can really love it, and I can feel like I possess it. I can own it, and then I give it away, hopefully for money, but I give it away, and then it belongs to other people.

Who may be discovering it twenty years from now, for all you know, once they’re out there, they’re out there.

Yeah.

OK, so that’s why you write. Why do you think, in the bigger picture, why do any of us write? Why do human beings do this strange thing?

Well, I think storytelling is a compulsion. I think I think we make stories out of anything. I mean, you know, look at a newscast, right? They don’t just tell you this happened, they make a story about it so that you’ll be involved in it and you’ll care, and so I . . . because we’re in a covid pandemic right now and one of the things that television can shoot safely is reality TV because they can get everyone in one place and isolate. And so, I’ve watched a lot of that. And one thing that I’ve noticed is that if you’re completing a project on some reality television show, you have to tell a story about . . . it’s not just, oh, I made this cool thing. This is this, this story connects to the deepest wellsprings of my childhood, and it’s all about my grandmother, who passed away just two months ago. And I’m still, you know . . . and the audience responds to that. It may not even be true. In fact, it probably isn’t. They probably learned that they have to tell that—that soap opera is where you’re going with these kind of shows. S I don’t know why anyone else writes. I’m glad that they do. For some people, it’s a bucket list. They actually have “write a novel” on their bucket list, and then they write it and either sell it or self-publish it, and then they go on to the next item on their bucket list. I don’t understand that at all. It’s just too much work to write a novel just to tick off something on the list.

Yeah, just beat your head against the wall. It’d be simpler.

Yeah. And some just write for mercenary motives, which I don’t get either. Because so far as I can tell, these people aren’t rich.

Yeah. And the third question is, why write stories of the fantastic, specifically science fiction and fantasy. Why do we write about things that aren’t real?

Well, in my case, it seems to be what I’m good at. I just seem to come at reality from a somewhat sideways perspective. And, you know, I have written other stuff, and I have a whole lot of unsold fiction sitting around n other various categories, literary fiction or mysteries or whatever. But what I kept being told is this is too strange. We can’t publish it. They hardly ever say that with science fiction. And when I write science fiction, I can write about anything, so long as it has certain science fiction elements. So, war and revolution from the point of view of star-crossed lovers. I wrote the world’s only Gothic Western police procedural, a science fiction novel called Days of Atonement, set in Silver City, by the way, really a fictional analog Silver City, but if you know New Mexico, you know where you are. You know, I’ve written cyberpunk, I’ve written anthropological science fiction, I’ve written, I don’t know how to describe it, gonzo science fiction, I guess, really high-concept stuff. I’ve written near-future science fiction that actually got overtaken by events. I wrote a novel about the Arab Spring, and it appeared the week that the Arab Spring started. So, that’s one of my more successful predictions, I’d like to think. And oddly enough, no one cared. My agent was out there contacting every news organization in the world, saying, “my writer predicted that this was going to happen, and the book is out, and you should talk to them.” And they said, “No, we have our own analysts. We pay them.”

What was the name of it?

Deep State, the middle book of a series about alternate reality gaming, oddly, and they are also now all available for me as ebooks. But it begins with This is Not a Game, is the first one. There are four, although the last one is a novella. But it was interesting going back because I just, you know, once I mounted my own editions, I went back, and I was reading the reviews, and one of them said, “These are really good books, but this is in no way science fiction.” And I said, “They were science fiction when I wrote them. And then it all happened.” So, once again, it’s kind of a matter of timing. I wrote a Black Lives Matter novel twenty-five years ago called The Rift. And it was such a colossal commercial failure that I didn’t sell another book for five years. So timing is everything. If I were to write a Black Lives Matter novel now, it might do better.

Or there’d be so many of them that it would get lost in the . . .

Yeah, that’s true.

So, what are you working on now? You’ve touched on it a little bit.

I’m working on the next book In the Praxis series, so Fleet Elements is to be followed by The Restoration. And I’m about halfway through that book.

When is it expected out?

Probably late 2022. Because I’m scheduled to deliver it later this year, and it will spend at least a year in production.

And anything else?

Yes, I have my Quillifer series, which is high fantasy and my love letter to the English language. The third book of that will appear around the New Year. I don’t know. The final schedule hasn’t been decided yet. It makes me happy to write these books. It’s just a delight to write Quillifer, because he’s just so, so much fun. And they are sort of a swashbuckler, Rafael Sabattini meets Michael Moorcook meets Tolkien, I guess. He’s a kind of impish character, and I like writing these characters.

So, lots for people to look forward to, it sounds like, in the not-too-distant future.

Yes.

And of course, the short story . . .

And they can prepare for it by reading the two earlier books in the series, which are Quillifer and Quillifer The Knight

That sounds like my cup of tea, so I’m going to check those out.

Please do.

And where can people find you online?

Uh, www.WalterJonWilliams.net. I’m the only person I know who has a .net instead of a .com, but somebody had already stolen my identity with the .com.

And just for those who don’t know—you should know—it’s Jon without an H.

Yes, yes.

All right. Well, thanks so much for being on! I enjoyed that. I hope you did, too.

It was great fun. Thank you.

And we say hi to Nancy the next time you see her because she was a guest on here not too long ago.

All right. Good talking to you!

Bye for now!

Bye-bye.