Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

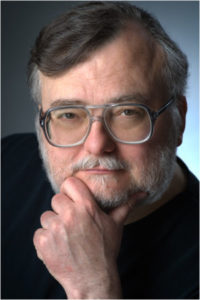

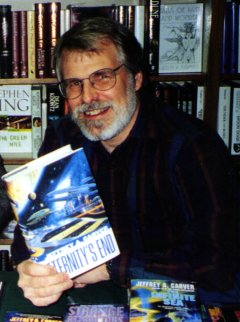

An hour-long conversation with successful screenwriter and novelist Edward Savio, author of Alexander X, Book 1 in the Battle for Forever series, the audiobook version of which, narrated by Wil Wheaton, was a number-one overall bestseller on Audible.

Website

edwardsavio.com

Twitter

@EdwardSavio

Instagram

@EdwardSavio

The Introduction

Edward Savio grew up in the bucolic bedroom community of Berlin, Connecticut. After Howard University, he moved to Los Angeles to pursue screenwriting, where he became a ten-year overnight success, selling the first of a half-dozen scripts a decade after arriving in Hollywood.

Savio’s first long-form novel, Idiots in the Machine, was his anti-screenplay, giving him the freedom to explore and develop deeper characters, multiple narratives, and play with language. He wrote Idiots with the certain belief that no one could make it into a movie, not even him, and then Sony Pictures optioned Idiots for the Academy Award-winning producers of Forrest Gump for seven figures.

After three more six-figure deals with Sony and Disney, Savio moved to San Francisco to start a family. And after years of commuting between homes in SF and LA, he chose to shift the focus of his writing towards novels so he could spend more time with his children. He lives and writes in the home where Danielle Steel wrote her first two breakout novels.

The (Lightly Edited) Transcript

So, Edward, welcome to The Worldshapers.

Hey, how are you? Good to have this time with you today.

I like your first name. You’re the first Edward. I’ve done it on the podcast.

So are you…see, I’m an Edward. Are you an Ed or an Edward?

I write under Edward. That’s my byline. But people that know me call me Ed. Unless they knew me in high school. Then I’m Eddie. So it’s one easy way to tell when somebody knew me, is by what they call me.

See, I used to be Ed in high school, but then when I got to college, people, you know, across the campus would be yelling, “Ehh!”, like, any noise, and I just kept turning around. So finally, I was like, “Okay, can we just be Edward?” And it just worked out that way. But yeah, I mean, I know. And of course, my mother, when she’s upset with me, would call me Eddie. So I have those three personalities as well.

Yeah, I was always Eddie right up until I started working for a newspaper. And then I decided my byline as Eddie Willett…I was only twenty when I graduated from university and started working as a newspaper reporter, and I decided I needed to seem older than I was. So I went from Eddie to Edward at that point. And it’s been my proper byline ever since.

Smart.

So, we’re gonna talk about your series, which started with Alexander X, but before we get to that–and, of course, the real focus of this podcast is on your creative process. We’ll use that as an example of your creative process–but before we do that, there’s a…it’s kind of a cliché on The Worldshapers, and someday I’m going to put reverb on it…I’m going to take you back into the mists of time and find out how you got started at all this. I know you grew up in Connecticut. Were you a big reader? When did you get interested in words?

You know, it’s funny. I am a student of words. I love words. I didn’t start out that way. You know, I think, like, how did I get interested in writing or writing sci-fi or writing worldbuilding? Like, there are so many different questions there. Which one do you want to start with?

Which came first?

Writing. You know, I think with writing, I have to say that I was a…most writers start out as readers. Right? I was not a reader first. I really wanted to become a director when I was a kid. I loved movies.

All you really wanted to do was direct.

All I really wanted to do was direct. And I knew that from the time I was in seventh grade. And I knew that the two most common ways to become a director were through the visual side, cinematography, cameraperson. And the other was writing. Actors, of course, have become directors, but most directors come from either cinematography or writing. And since I didn’t have a camera and I couldn’t develop my own film, you know? I wrote–a lot. I wrote dialogue-heavy plays and then screenplays, and I wrote a musical in order to graduate high school, because in between my sophomore and junior year in high school, I went to France and French girls just kind of got in my head and I needed one more credit to graduate, and so I had to do an independent study at the end of, or during, my senior year, when everyone else was loafing. And a lot of it was comedy and action, but when I wrote prose, it was always short stories, and almost exclusively science fiction. The screenplays I wrote, they might have a magic element to them, but almost all of them were mainstream comedies and actions.

So, after selling screenplays to the studios and making a good living and writing mainstream novels, I wanted to go back to my roots, and I think writing sci-fi and building a world is a way to do that. And, you know, there are so many ways into science fiction. As a kid, I–because I was this visual person because I wanted to do movies. You know, I loved watching Lost in Space before school or, you know, of course, the Star Trek reruns. That’s how I got into sci-fi. And I didn’t begin reading the classic science fiction until I was in my 20s. And I have this inverted life, right? Like I said, most writers, a lot of writers are big readers.

I think you’re the first one I’ve talked who said they didn’t start as a reader.

So, yeah, I mean, most people do that. And I was always a big writer. I wrote my way out of everything, feelings, and all of that. And so, I made a lot of mistakes that probably would have been fixed if I had read more. But I made my own mistakes. But that’s how I got into the idea of writing and specifically sci-fi.

When you were writing whatever you were writing as a kid, were you sharing it with other people and letting them see what you were doing and getting feedback that way?

Yes. So, you know, I wrote a lot. I wrote poetry. I would read it. It would be, you know, like I would read it in front of a class or do it in front of an assembly. I did stand-up comedy in front of assemblies when I was a kid. I did this musical that needed to be performed in order for me to, you know, get the grade. So, yeah, I was not shy about showing my work, but it was funny, when I went and talked to my English teachers, my English teachers looked at my work and went, “You’re writing in present tense all the time. And you should be writing…this sounds like a script.” And I was like, “Yeah.” So, even my prose, in the beginning, was in present tense, which helped me a lot. You know, I go through and use a lot of different tenses, even in the same book, because, you know, with Alexander X, there’s the past, but sometimes in the past, I’ll use the present tense. But I use tense to either make the action more visceral or to show a difference between when someone is talking and when someone is talking about the past, even if it’s reversing the present tense versus the past tense. But yeah, I didn’t have a problem with showing my work to other people. And I know that’s a big problem for a lot of writers. They just never show anyone that first work. And I’m so glad I did it early on because, you know, I’m proud of everything I’ve written. But the stuff I’ve written when I was younger, it’s still pretty good, but it wouldn’t have gotten better if I didn’t have some feedback.

And that’s why I always ask. Because it does vary from writer to writer. But…I was someone who wrote my first short story when I was 11, and it was called “Kastra Glass: Hypership Test Pilot,” so you could see where my mind was right away.

Exactly.

But I was always sharing it. And it was…if I hadn’t shared that story with a teacher who gave me some critiquing on it, I might have not had that little spark that made go, “I want to keep doing this because readers actually enjoy what I’m doing for them.”

Yeah, I mean, I always made people laugh in school, you know, or I was the person that, whenever we had a big assembly, I would be, like, the M.C. or the person that would gather…you know, would be up at the mike. I was not shy about that.

You know, you mentioned something about the musical. Did you perform in that? Did you do some acting as well?

I did. I’m an average-to-poor actor, you know. I was just watching Hamilton this weekend…

So were we!

…and, you know, I’d seen the play earlier this year in person in San Francisco, and it was amazing. And I think they did a great job in what they showed in the film. But it was interesting because, you know, as much as it is…I wanted to see Lin-Manuel do this because he is amazing at it, but he’s the writer and the creator. And in many ways, most of those other people are better, quote-unquote, actors than he is better singers than he is. He brought something no one else could bring to that part. But that’s how I would feel if I was doing something. I don’t even know if I’d be that good at all, but I’m saying that when I did my own stuff, when I was acting in my own stuff, I was the weakest link of it. But the writing is what gets you. And then also, understanding playing things is important.

One of the things that people have talked to me about is, in the Alexander X series, Wil Wheaton is the narrator. And people have said, “You know, is it weird when he does something different?” I said, “Well, a lot of novelists get weird about when someone makes a choice about their words. That’s all I started out with. I was never going to be the one that was in your head. When I wrote a screenplay, it was never going to be me telling you this story. It was going to be someone else. It was through someone else’s filter.” So, for me, it was actually a lot easier. I think it’s a lot harder for some writers to make that jump from book to audiobook. When they hear it, they go, “Oh, God, I didn’t mean that.” And it’s like, “Well, yeah, you didn’t, but a performance was built and was born out of your words.”

Well, I’m a stage actor, and I’ve talked to other authors who have some sort of theatrical experience. And I do find that it gives people a different idea on their regular writing. One thing that I often say is that, you know, you’re talking about, “Does it sound weird when somebody makes a different choice with the words than you did?” But that’s exactly what happens in every reader’s head. You don’t know how they’re hearing those words in their head. They’re essentially acting them out in their head the way that they would interpret them if they were an actor on stage. So really, everything that we write is being interpreted differently than we perhaps have it in our heads as soon as it crosses over into somebody else’s head.

I agree. I mean, I remember driving home from this girl’s house at like 2:00 in the morning. I was, like, seventeen years old or something. And I remember we had just, like, been, we were making out, it was like this my whole mind is like, “Oh, my God, this is amazing.” And I’m driving home, and it’s late, and this…I don’t know who it was, it was a late-night deejay or something…and he gets on, and he says this sentence and I will never forget it. And it’s absolutely influenced my writing ever since. And he said, “I can say the words ‘I never said he stole my coat.’ And if I inflect each word differently, it changes the meaning. I never said he stole my coat. I never said he stole my coat. I never said he stole my coat. I never said he stole my coat. I never said he stole my coat. I never said he stole my coat. I never said he stole my coat.”

I’m going to remember that now.

Yeah. Each one of those means something different. And I will never forget that I’m gonna write this sentence and someone can read it, as many different words as are in there, they can put an inflection on there differently. And so, in writing, you know, I do use italics at points where I really feel like something is necessary and has to be there. I let the reader have their own mind for a lot of it. But I learned because of writing screenplays that I needed to be very specific in how I wanted something to be said. An actor and a director are gonna do what they’re going to do. But at least you have to give them your intent, so they can go, “I don’t want to do that.” Or, “Oh, I get what you’re saying here and I’m going to bring something different to it.” But you at least have to give them the intent. And it’s a wonderful thing.

One of the things that I find most interesting about writing is when you get criticism. People, you know, people tend to be only either lovers or haters when they write a critique. There aren’t a lot of “meh” in-between critiques. And what’s funny is when someone is negative, when someone doesn’t like something, it is usually not liking the very thing that either I as the author or the majority of people who love the piece enjoy. It, you know, someone’s like, “Oh, you write too much about history,” or “You do this or X or that.” And it’s like, and then other people are like, “I love when you go into the deep dives into history.” And so, you know, he can’t make everyone happy. But, you know, you’re at least trying to find your audience so that…it’s interesting, like, the first book, Alexander X, has a very good rating. But the second book has a much better rating. Now, is it because I wrote so much better? I think it is a better…I mean, I’ve developed the story, it grows…but I think it’s because I’m starting to find the audience and the people that aren’t going to like that first book aren’t going to go to the second book.

I think it’s Robert J. Sawyer, whom I interviewed, that said that you’re not trying to be…it’s impossible to be the favourite author of everybody, but you want to be the favourite author of a nice, solid chunk of people, is how most people find success. It’s not by being the most popular author of everybody, because you can’t please everybody.

No, you can’t. You really can’t. And you can’t even try. And, you know, you can’t even try. It’s just something that that doesn’t work. So, you know, I think one of the most interesting things about building a world, and that’s what you love to talk to people about, and I think in your own work, you love to build worlds, is that, you know, we get to create something. I’m not a believer in simplistic worldbuilding because, you know, when you have everyone, you know…there’s movies, television, there’s books, where you have a conceit, and you break people into five different groups, or you have certain different factions and those factions are very, very cut and dried. Well, if it’s a metaphor, I get it. But in the world, most things would never happen like that. But it is interesting to be able to create a world that is both familiar and shines a light on who we are, yet brings us into something completely different. Alexander X is very realistic science fiction, and so the worldbuilding is about the people themselves. I’m coming out with something, it’ll probably be next year, called Flux Capacity, and it is a very different concept, very much where I can go and play in this playground.

You spoke about, you know, Idiots in the Machine being the anti-screenplay, my first novel. I didn’t start writing sci-fi in terms of long-form until my kids were a little bit older, and I wanted to write something that they might be interested in. And that’s how, you know, I came about to write Alexander X. But with Idiots in the Machine, you know, I had this idea that I was going to just do the opposite of a screenplay. I was going to…I was tired of, you know, before I sold my first screenplay to a studio, I had written fifteen, maybe eighteen screenplays? I had made money, a little bit of money, from about the eighth or ninth? I was a starving writer living at about eight to ten thousand dollars a year, you know, living with roommates, living my life, not working other than writing. And then I started to write this novel, and nobody cared at all. No one gave me any money. And so, I had to start working. And so, I worked at this talent agency, and I got to see how the product was handled. And I learned a lot of things about the business. Those people never helped me at all. But I did meet someone who was an assistant, who became my agent, who helped change my life. She introduced me to the woman who became my wife and the mother of my children, and also, I learned about lit agents, and she was a talent agent, and I worked with her and developed how we could talk to people about the scripts. But, building a world is something that starts…it starts with a kernel of an idea.

Well, just before you get there, because that’s the main focus of what we’re gonna get you in a minute, I did just want to back you up to the university level. Did you study writing formally at some point?

So, again, I was very much a film person, you know, and I went for screenwriting and for film making. And I ended up just writing and writing and writing and writing and writing while I was doing that and it became the thing that I realized…again, learning how to get behind the camera was okay, but if I was going to do anything I had to be writing, I couldn’t be…it couldn’t be someone else’s…I couldn’t take someone else’s vision. I had to take my own vision if I wanted to be out there. That was the risk I took. And so, there were plenty of people that made more money in the beginning because they went and worked in the industry and moved their way up through things. But what I did was I took a gamble and, you know, I paid a lot of…you know, cheap food when I was in my twenties, but I put…I invested in what I felt was my best chance, which was to create my own things.

So now we’ll go back to the kernel idea. Because I want to go through your creative process. And the very first thing is, of course, that kernel of an idea. So, where do those kernels come from for you and specifically for the Alexander X books?

So, Battle for Forever…

Oh, one more thing before we say that. We should have a synopsis, so people know what we’re talking about who haven’t read the book.

So, yeah. So, okay. So, Alexander X. So, here’s the kernel, the start, right? So, the idea is…I had this idea as a screenplay idea, that there was this guy who was very good at everything. Mid-thirties. And what we find out is he’s a couple of hundred years old. And so he’s able to be really good at everything he does. And I put that idea away in a drawer. And then later on, when I was thinking about writing for my kids, I wrote this book called, you know, it was called The Stuperheroes vs. Dr. Earwax. And I did the illustrations that were just horrible, but they loved it. And my kids read up. They read above their weight class. And so, I started thinking about teenagers and young adults. And what if this character wasn’t 200 years old? What if he was a hundred times that, or a hundred times as old as a normal person? And what if it wasn’t one character, but maybe a few hundred? And they’ve been kings and queens and generals and some of the most famous people in history. But they’re not immortal, right? They step in front of a train. They die. Except, they have this genetic defect–what we now know is a genetic defect–that kills most people born with it. But the ones who survive have lived many lives, pretended to die, disappeared, started again as someone else. But for the last hundred years or so, they’ve been mostly living in the shadows because fingerprints, surveillance, DNA, biometrics, make it too risky. If they become great or even well-known, people are going to figure it out, and even if they pretend to age and die, their secret is going to be revealed the next time they show up, the next time they want to be great again. And they want to be great again. And the older ones, they’ve never gone this long without that kind of power and adulation. So, what would they do?

Mm-hmm.

So, that’s the world. That’s before we even start the idea. That’s the backdrop for meeting our hero, Alexander X, who is a junior at a small high school in the Berkshires. And he’s known as Alexander Grant at the moment. And he’s never been famous or great, but he’s lived a lot, and he’s seen a lot, fifteen hundred years of it. But his mind, his body, and his emotions are that of a fifteen-to-seventeen-year-old. With all the good and bad that comes with that, right? So, everything’s going along fine and maybe a little boring, but fine, until someone tries to kidnap him and use him to get to his father, who is one of the most powerful of their kind. So that’s the jumping-off point. And Alexander is basically trying to figure out what the hell is going on. And so, that’s both the synopsis and the kernel of where the idea came from.

Spreading it out a little wider, how do how do story ideas typically come to you? Not just this one, but of all the things that you’ve written?

You know, I mean, so for me, you know, I have a lot of different ways. I have three different ways of putting information down. And I have hundreds of snippets of stories and thoughts and ideas. Things have come in many different ways. You know, one of my original…originally, screenplays, sometimes we would take an idea that was a classic. And so, the first thing sold to Disney was Swiss Family Rubinstein, which was, you know, it’s Swiss Family Robinson, but written for if Bette Midler and her family are rich in New York and they get lost on an island because of all of this reason, what would that be? So, it’s like taking a kernel of something old and making it new again.

Or, it’s a snippet of something. I read–for Idiots in the Machine. I read the front or the back cover and saw the cover, the book cover’ and read the first few paragraphs of a book called The Confederacy of Dunces. It was just a brilliant book that won the Pulitzer Prize. And I thought it was gonna be a certain book. It ended up being this other book. But a couple of years later, I was thinking about my first thoughts, about the ideas I’d put down when I first picked up that book in the bookstore before I ever read it. I had driven home thinking about what this book was gonna be. And I wrote that book. I wrote the book that I was thinking about, you know? So there’s…so, I am still…I am…like, about half of what I write is something I thought of 15 years ago, and the other half is something…like Flux Capacity is a new idea. Alexander X, I had that idea ten years before I wrote the book. So, they come from different places. And that’s why you just have to…honestly, the greatest advice I can ever give to anybody is–and I’m only about seventy percent of the way there–is have the best, most searchable database of ideas that you can so that you can go find them and look things up when you need them.

Once you have the idea, I’m looking at the novels here, what does your planning process look like? Do you do a detailed outline? Or do you just start writing?

So, when I was writing screenplays, I was, oh my God, I was completely so very anal. I’m not an anal person at all. But in writing, I have to pretend to be one. And I would go through and use index cards and later use programs that mimicked index cards and write out everything, you know, everything, including indirect dialogue, including the major type of scenes. And then, by the time I went to go write the screenplay, I was going boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, and I’m there. When I wrote Idiots in the Machine, again, because it was this anti-screenplay, I did exactly the opposite. I had an idea–that, because, it was this thought in my head, through this idea that I had with the book–and I might have had an ending in mind. I had this vision, this one shot. It’s one image. Like I was filming a movie. I had one image. And then from everything else, I went and just went off. And so it’s all of these…imagine you take your fingers, your ten fingers, and they’re all spread out, and they’re just completely separate, and then all of a sudden they start interlocking like a zipper till the end. And that’s how it went and how it came together like that. My anal side kind of came in about halfway through the process, but it started out freeform.

Now, my writing process is a little bit more of both. I have three different ways that I write. I have tablets and digitized paper where I make some longhand notes. Obviously, I do most of my writing on a computer, typing. But I also make notes using voice-recognition software. I have a large space where I work, with screens on either side of this room, and I have a headset like those that the pop stars or the performers in Hamilton use. And I will walk around and act out action scenes. So, I may peek my head around the corner, pretending that I have a gun in my hand or I might block out how I’m going to do a fight scene. Now, I have large windows in my place, and it may be possible for my neighbours to see me from some angles and I can only imagine what they think of me when I’m doing this. I must look like a complete crazy person because I am literally fighting with myself and acting all of this out. And so, I put those things down on…you know, the biggest problem as a writer, my most time-consuming thing is to then reorganize those stream of consciousness ideas, which are well-formed in their little packets, I can write a whole scene or a section of a scene, but it’s reorganizing them in a coherent way to make them into a book because that…you know, they’re just ideas until you put them together.

Once you start doing that, do you work sequentially, then?

I tend to work sequentially, mostly. I will write big scenes. I may write a rough draft of an ending, you know, somewhere around halfway through the process. I already know something of the ending, usually. As a screenwriter, I’ve always started with two things. I know the first shot. I know what’s going to, what I’m gonna see, and so I know the first words or the first image in a book, and I’m going to know the last image I want people to know. And…but I tend to work sequentially. I tend to write and rewrite a lot of the first part of a book, you know, getting through till I’m comfortable, at least with usually about a third of it, about maybe 40 percent. And then I start moving onward.

And one of the reasons why I really develop the beginning is because spending time there at the beginning really makes the last part go a little bit faster, where I have a voice, I have a style, I have a thing that I know what I’m doing here, and I can go through and move further. I tend to do a lot of rewriting. Rewriting is, you know, I think…I mean, I think many people talk about this, right? But rewriting is the most important thing. And I do this one process where I write on a piece of paper or a digital version of it–usually, I use a PDF and an iPod–and it’s non-destructive editing, and I can make all the changes that I want, put funny lines in or ideas that I have, and nothing has changed in the original document. Because going into a computer is destructive editing, and a lot of writers have…they clench up, they get constipated, they literally clench up, and they can’t move forward because they’re like, “Ugh, I don’t know where I’m going.” But when you do it in a non-destructive way, you can do anything you want. And then later on, when you come back and put it into the computer and put it together, “Yeah, I guess it’s not that great of an idea,” or, “That other idea that I had later is completely contrary to this idea.” So, let me work those two out before I’ve done all this work.

I think you’re the first one who has told me of a process quite like that. People revise as they go, but most of us tend to just do it on the computer and not have a separate, non-destructive way to make those suggestions to ourselves and then come back to it.

It’s really the most freeing thing. It really is. I mean, it is the most freeing thing. And when I figured out how to do this–because I used to do it on paper and have these thick, just reams of things that I would always lose or, like, I couldn’t find them when I needed them. And on a PDF, I can at least search for the words near where I’m looking for or something, and I can just put it right there, and it’s on my iPad and then, “Oh, it’s on my computer right next to my what I’m working on.” It is the most freeing thing I’ve ever found.

I know it’s happened to me once or twice where I have rewritten something and then think, “You know, the original maybe was better,” but I don’t have the original anymore.

Right.

So, yeah, I can certainly see to see the benefit of that. Do you…it sounds like, with the process you’re working, I’ll bet you work almost entirely in your dedicated writing space, and you’re not somebody that goes out and works in a coffee shop or something like that.

I don’t work in a coffee shop, but I don’t work necessarily in a dedicated space. I actually have a few spaces where I write. So, I’m…right now, I’m in the booth where I do audio work. So, this is a creative space. But in terms of writing, I have three other creative spaces for the actual writing. I have a stand-up desk where I do a lot of this walking back and forth with this monitor on the other side of the room. I will go out on my balcony, and I will take my computer out and write looking out at the bay. You know, this house, this place has a lot of Chi, writing Chi, you know, Danielle Steele wrote two of her books here, so it really does have a good feel. And I use her bookcase. She built this one bookcase in here, this big, giant bookcase, which is my quote, hallway library. But I also can go and walk and talk, and I may go out and ride or walk and make notes to myself out in different places, because sometimes that is the most amazing…like, you get stimulated by whatever you’re seeing.

You know, I was, I got to go to Rome last October and some of the scenes in the third book in the Battle for Forever series, take place in Rome. And I already had an idea of what I was going to do. I already knew–I didn’t know if I was gonna go there. I was going there for… A friend was having a birthday party and I got invited, and it was this eye-opening experience. I’d never…my family is five generations on one side and four generations on the other of Italians. But we’re not, like…because we’ve so been here so long, we’re not like the new Italians coming over. So, you know, we have this, a little bit of our culture, but I had never gone to Italy. And I’ve been to Paris, I’ve been to Europe, I had all of these things, and I put them in my writing. But when I went to Rome, I was like, man, I could not have imagined what I’m looking at. The pictures don’t do it justice. The feelings that I’m feeling don’t do it justice. And I just started to walk around and mostly…like, the first couple days I just experienced. I didn’t try to intrude on my experience. But there were moments, you know, where I would pull out my phone and make notes to myself, audio notes, or think about what I was doing or where I would put this, and almost kind of do a live version of that thing I do in my house where I’m blocking out something. I might be in a place and go, “How would I run up these stairs if I was going to do something illegal here? How am I gonna get to that roof if I’m gonna use that great piece of architecture, you know?”

And so,. I think it’s important…a lot of writers create…you know, when I was younger, I had a small little room, nine by ten, and I used to sit in it, and I loved writing like that. And a lot of people love that little cozy writing space. But I also think it’s important for writers to get out and create in an open space. Take your computer, take your iPod, take your…whatever you’re doing, and go completely off-grid or in the middle of a city and start writing something. And maybe later on, it is going to turn out to be nothing, but it might be the kernel that you need for a scene or a whole story.

Yeah, I think the most productive I ever was, was getting out of my office and going to the Banff Centre for a week, for a self-directed residency, and I wrote 50,000 words in a week. You had this magnificent mountain scenery all around you. And it…although the odd thing was, the book I was writing was set on the prairies, but it was still…it was, you know, just the change of scenery alone stimulates, I think. So, once you get the first draft…well, first of all, are you a fast writer, would you say, or how does this process work?

I’m a bit…I’m about…I would say that I’m a fast writer, with a ponderous amount of pondering. So, when I’m writing, writing, I can do a lot of work, but when I’m thinking, it’s a long time, and when I’m editing, I can go through and agonize over a sentence or, you know, a group of phrasings here and there. So, it’s a little bit of a mix. I would say that overall, I’m not a fast writer. I’m not a slow writer. But I’m very fast and prolific at certain times.

When you get to the end, with all the revision that you do as you go along, is there then still a complete revision process for you where you go back to the beginning and work your way through? What does that look like?

I am, you know. Yeah. I mean, I am literally just…I am constantly rewriting. You know, I have…it’s very funny. So, I wrote the Idiots in the Machine years ago. And finally, you know, now that sort of had this second boost through Alexander X and everything…you know, I had a successful career as a screenwriter, and then, you know, I had this book that did something and then, you know, I raised kids and didn’t do much because I wanted to raise my kids, and I changed my life. I would fly back and forth, but it became too much if I wanted to be…and have a life. And so, it was a difficult choice, but I didn’t…you know, I kind of got rid of my apartment in Los Angeles, even though I kept it for years, and I just started writing.

But so, with that said, this book came back into the realm after Alexander X hit number one on Audible, and the opportunity to do an audiobook version of Idiots in the Machine became real, and I could get the type of people that I wanted to get. I rewrote some of it. I rewrote some of it because I looked back at it as I was going through and I was like, well, you know, I mean, most of it was just things that didn’t play well to me or just didn’t, you know, didn’t seem to age well? A joke here and there where you’re just like, “Okay, that doesn’t work.” And I’m always reminded of this thing that Tennessee Williams said, you know, someone was interviewing him, he was in his 80s, and they came into his office, and he had Cat on a Hot Tin Roof on his desk with pencilled notes on it. And they’re like, “What are you doing?” He’s like, “It’s not finished yet.” It’s been a movie. It’s been a play on Broadway. No one’s going to redo his thing. But to him, it wasn’t finished yet.

So, yeah, I go through, and I rewrite a lot and, you know, I use that, like I say, that non-destructive editing. I go in and I write. I have people read and give me some notes. I don’t very much listen to notes directly. And I learned this in screenwriting where I almost got fired off of a job because I actually listened to the studio executives. I came back with this version based on every single one of their notes. I had gone down, point by point by point, and done everything they wanted, and they’re like, “This is horrible.” And I’m like, “This is all, these are all your ideas.” I mean, that’s what I wanted to say. So, two things happened after that. From then on, I walked into meetings and I would put a recording device in the middle of our meeting, and the red light would stare at them, and they became seventy-five-percent smarter, knowing that their voices and their ideas would be saved for all eternity. And the second thing I learned was, don’t do what they say, do what they mean. And if someone or a few someones tell you something’s wrong, their answer is not right. But they do, they are coming up against a speed bump or a pothole in your story. And you need to figure out how to fix that.

How do you find the people who do this reading for you? Are they just friends, or…?

It could be. Yeah. I mean, so, I have a group of maybe about a couple of hundred people who have grown to love this so much that they’ve kind of, you know, the first two books, I’m giving them pieces of things. In general, you know, my kids were really important in reading this. They are really tough critics. They do not pull any punches. I have a few adult friends who have read things. My manager or agent will look at stuff, you know, but it’s mostly been people that are that I know or that love something already.

You know, here’s the thing. It’s always tough because when you give something to people that are fans of your work, they tend to, you know, either they’re really helpful, but they want to love it, and they also feel like, well, you know, you’re the writer, and they’re going to say nice things to you. So, I usually have people that I say to them, “Hey, I know it’s really good. You don’t need to tell me it’s really good. You need to tell me what you have a problem with. Again, I may not listen to anything you say, and I’m probably not going to listen to any of the ideas that you have. But I’m going to listen to what you mean and why you’re saying that. And I may ask you some questions about that. But don’t be afraid to be critical.”

Now, it’s published by Babelfish Press...

Yes.

Do you bring in editors or an editor that works on it at some point?

You know, so yeah, I mean, we did this…Babelfish is a very small thing that I started with a couple of writers and literally, the people…we are now getting interest from bigger publishers, which is one of the reasons why I’m sorry, readers, that things are taking a little bit longer because the process is a bit…is a bit more lengthy, but we’re working through that. So, you know, I’ve had editors work with me, but really, the most important thing is that you have people that know how to write. You have people that know how to read. And they tell you what’s wrong. And, you know, my job is to try to figure out a way to fix it. And one of the things…if I’ve gotten any good compliments in my life, there’s one thing I’ve heard, over and over, which is, “I will take your criticism. I will not get mad at you, I will not do that, and I will try to find a solution that not only makes, you know, not only answers your problem but also tries to take it to the next level because you’re challenging me to do something better. And if I’m going to waste…not waste, but if I’m gonna take time to address something better, I better well address it, you know, as best I can.

Now, we mentioned the audiobook, obviously, with Wil Wheaton. How did that come about? That’s a pretty top of the line, narrator you got there?

Yeah, so. So, well, a couple of things. You’ve interviewed John Scalzi, and I’m a big fan of Scalzi’s, and I’m also a fan of Ernie Clines’s Ready Player One. And so…you know, when I was writing this, I didn’t have a voice in my head. I had my own voice. But I was…I had been reading…so my kids, again, read above their weight class and to keep ahead of them when they were younger, I would read and also listen to audiobooks because I’m out walking around or doing something or working out, and I would listen, because my kids could just read much faster than I could. And they had more time to deal with that. And so, I started listening…one of my sons got Ready Player One as a gift. The book. And I got the audiobook and the book, and I was reading the book, and I also was listening to the audiobook, and I was like, “Wil Wheaton. I like Wil Wheaton. This is great.”

And then, I also had read John Scalzi’s earlier work, Old Man’s War, which was not done by Wil Wheaton. But then I started getting into his later work, and I was again, I’m an adult, I don’t have as much time to read, I listened to some of them, and a lot of his later work, most of it now, is done by Will. And so, when we were sitting down to come up with narrators, I had a first, a second, and a third choice. And every single one of them was Wil. And I just…I just fought for the ability to do this. And luckily, the people…Wil goes through and will read what he’s…obviously takes a look at what he’s going to look at, and he has, he’s very picky and only chooses certain things. But before you can even get to Wil, you have to get through sort of a gauntlet of a few people that know what he likes and know his wheelhouse. And Wil started out as…I mean, you know, this child actor…

We just watched Stand By Me with my daughter not too long ago.

It’s great. Right? Amazing. And he’s this child actor who then grew up. And so, in some ways, he’s really perfect for this because this is a teenager, this character, who is really an old soul. Right? So, a lot of people have, you know, until he went on to other things, you know, his voice work and Big Bang Theory appearances and things like that, they always thought of him as this teenager. And he was kind of locked into that and battled with that personally, about how that affected him in his business. And if you read his blog or his writings, he talks about that, and he’s come to terms with it. And it was so…and he brings that to every sentence in this book. He brings that lifetime struggle that he dealt with to this struggle that this lead character deals with. You know, he is a fifteen-to-seventeen-year-old biologically. He has all of the hormones, the brain, the brain development, everything of that. But he’s lived so long, and he’s got so much information, but he doesn’t have the maturity. And he struggles with what that means and how other people see him because he’s smarter, knows a lot more than someone who is going to look at him and go, “Oh, you’re just a teenager.” So, it was a really great thing. And when I heard him, when I heard the first version, I was blown away. And what’s funny is, I’ve done voice work, and I recorded a new book that’s coming out of mine that’s an adult, you know, mainstream fiction. And it’s called Velvet Sledgehammer and very personal, so I really had to be the one that did it. And the amount of time and effort and strength and, you know, exhaustion that you feel working to get this done. You know, he did a 10-hour, 45-minute recording in, I don’t know, you know, four days or something. Five, four, you know, four and a half days. And it’s insane how someone could do that.

Yeah, I’ve done some myself. And it is…it’s the time commitment and everything else that goes into it. It was way more work than I anticipated when I thought, “I should do some audiobook recording.”

Yeah. Everyone’s like, “Hey, how hard can it be.” Yeah. And you know, it really…and what I love also, Wil opened up a whole different audience for me. And also, he…you know, everybody’s like, “Do you think about what he’s going to say, how he’s gonna sound?” And I’m like, “I don’t think about how he’s gonna sound.” But I was really thankful that…before I ever did this, I always had a problem with the he-said-she-said nightmare that happens in books, you know, where…when we read he said, and she said, we don’t see them.

Yeah. They’re pretty much transparent.

They’re transparent. They’re like names on a script, you know, the character names, or in a play. We don’t read them, we just know who’s speaking. But when you hear them, they become very annoying. And so, I was glad that I had figured out a lot of ways to avoid a lot of that repetition before, because if…because, I just felt that way about even reading them. And I was grateful when he read, and it didn’t sound like some books.

Well, we’re getting close to the end of our time. So I have to ask you–this is where I need more reverb again, the big philosophical questions, which are basically why? Why? Why do you write? Why do you think any of us write? And specifically, why write science fiction? You’ve sort of talked about this earlier on, but now you get to sum it all up.

So, yeah, the big question. Why do we write? Why do I write? Why does anyone write? For me, the answer’s pretty simple. I have to write. There’s no choice for me. You know, like, it’s like asking like, whether I want to breathe or not. You know, we have to eat well, we have to exercise our bodies, but we also have to exercise our minds and whatever that means, right? Not everybody can do this or wants to do this, but human beings are human beings because we think. One of the things I talk about in the Battle for Forever series, one of the themes, is that you can do anything you want. You can become great at anything if you focus on it. Now, we don’t have hundreds of years to learn how to play the piano or study martial arts, but it’s a metaphor. And writing for me is something that I’m constantly striving to be better at. And in some ways, it’s this interesting balance of the, almost the opposite of what our English teachers taught us in high school, because as kids, we write very simple ideas, very simple sentence structures. And in school, we start to learn how to complicate our ideas, you know, with flowery language and big dictionary words. Right? And storytelling needs words. But we have to find the balance between how we tell a story and how we phrase it. You know, I’m a firm believer in the em dash and long, complicated sentences.

Me, too.

And I feel that in creative writing, the semicolon is like an intersection where everyone has a yield sign, and no one knows what to do with it. Right? In fiction, I think we should get rid of semicolons. But, you know, there are also these moments when you need to just write like you’re Hemingway, where it’s he did this, dun-dun-dun dun-dun-dun dun-dun. Right? It’s changing the different cadences. So, I have to write, right? It’s what keeps me sane.

You know, when I was writing comedy more exclusively, I didn’t think I was crazy enough to be a comedy writer. And in my thirties, I found out I was crazy enough. But I also found out that writing is like a daily meditation and therapy. And I think most writers, whether they are famous, not yet famous, or maybe never will be famous, that’s why they write, because they have to write. And I tell people I work with, people who have either interned with me or, you know, come to me for advice, that if I say anything to you, any criticism that I give you, because I’m going to give you tough, tough criticism, if any of it can stop you from writing, discourage you from writing, then you probably aren’t in the right business. Because there is nothing anyone can say to me about writing, no criticism, no negative comment, nothing that would stop me from what I’m doing. You know, because I have to do it. You know, and I just have to say one last thing about this, which is, I’m so grateful that others want to hear or read what I have written, what I have to say. It gives me pleasure, and it drives me farther, and it makes me try harder. But it is only the turbocharging. It’s the nitrous oxide booster, right? It makes it easier. It makes it faster. But it’s not the main fuel.

Yes, because most of us wrote an awful lot before anybody read any of it. And yet we still did it.

I would write if no one saw it.

Yeah, me, too. So what are you working on now? Obviously, there’s the next book in the…Battle for Forever, I guess, is the name of the entire series.

Yeah, Battle for Forever is interesting because there’s going to be four books and I’m writing the third, and the last book is going to be called Battle for Forever, which will really screw everybody up when they come to the series and they sit down and try to read the first book with the title of the series and they go, “Wait, hold on. This is…I’m in the middle of something here.”

So, I’m writing League of Auld right now, I’m about 90,000 words into what will be 110,000 words, but I’ll probably write another thirty or forty thousand before I start cutting back down. I’ve already…you know, I’ve probably already written about a hundred, a hundred and twenty thousand, and gotten down to my ninety, so… And I’m working on Flux Capacity, which is this cool, fun story that I’m working on as well. And I have this very inappropriate, totally not safe for work Velvet Sledgehammer story that is about basically the coming…a person who is reaching adulthood…well, their mid-30s, real adulthood…and is starting to face the fact that children are coming. And in the middle of creating what turns out to be the World Trade Organization, because he’s the trade representative for the United States, and it takes place in 1993, that he…his girlfriend decides that they should get married and have children, and he thinks he’s the last person in the world that should have kids. And so it’s this coming-of-age story for an adult and how we have to deal with all of the things in our past and our present and find those things in us to pass them on to the next generation and screw them up just right.

And do you have any dates for when these things will be appearing?

So, most of the things are in a little bit of a nebulous space because of dealing with the larger publishers. And…like, Velvet Sledgehammer is ready to go. And if anybody contacts me and they want to read an advance copy or they want to give me some feedback on both the audiobook and the book themselves, they can look at that. But they want to hold it back because it’s so different than my sci-fi stuff that they don’t know where to put it yet. But League of Auld by the end of 2020. And I will take a break and not finish the fourth book for maybe a year, year and a half. And in the meantime, I will finish Flux Capacity for next year.

And if anyone wants to find you online, where can they do so?

They can basically find me, Edward Savio, @EdwardSavio, Twitter, Instagram, dot com. Those are the best ways to get me. I will respond on Twitter and Instagram as well. I’m not on there as much because words a little bit more than visual are my thing. But that’s where they can reach me. And if they want to check out Battle for Forever, but don’t necessarily want to yet get into that, they can go to battleforforever.com, and they can get a free novella that is told from a different character, a female character who I just love, she’s great, who’s about 2,000 years old, and it will give you an idea both of the story and some things that might be coming in the future, but it will not ruin anything in the books themselves. You can read it before you read them or in the middle or after. It will just give you a greater understanding of what’s going on.

Okay. And when I do the transcript and everything, I’ll put links on the website, The Worldshapers website for the stuff.

Thank you.

So, thank you so much for being on The Worldshapers. That was that was a fun conversation. At least, I thought it was fun. I hope you did.

Yeah, that was good.

All right. Well, thank you so much.

Thanks!