Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

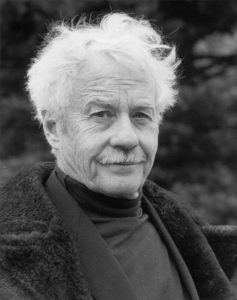

An hour-long conversation with James Alan Gardner, author of ten science-fiction and fantasy novels and numerous short stories, including finalists for the Nebula and Hugo Awards and winners of the Aurora, the Asimov’s Readers’ Choice, and the Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Awards, with a particular focus on his Dark vs. Spark series (Tor Books), which began with All Those Explosions Were Someone Else’s Fault.

Website

jamesalangardner.com

Twitter

@jamesagard

James Alan Gardner’s Amazon page

The Introduction

James Alan Gardner got his bachelor’s and master’s in math with a thesis on black holes, then immediately began writing science fiction instead. He has published ten novels and numerous short stories, including finalists for the Nebula and Hugo and winners for the Aurora, the Asimov’s Readers’ Choice Award and the Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award. His most recent novels are All Those Explosions Were Someone Else’s Fault, first book in the Dark vs. Spark series, and They Promised Me the Gun Wasn’t Loaded, the second book, both from Tor. In his spare time, he plays a lot of tabletop roleplaying games and has recently begun writing material for Onyx Path’s Scion line. In his other spare time, he teaches kung fu to six-year-olds.

The (Lightly Edited) Transcript

Welcome to The Worldshapers, James.

Thanks, Edward. Glad to be here.

I guess we’ve kind of known each other for a long time, but we don’t encounter each other very often. But we did see each other at When Worlds Collide, which is something…When Words Collide. It always comes out as When Worlds Collide.

Yeah, yeah. It’s a great idea and a great title. And it was a great con this year.

Was that the first time you’d been?

Yes.

It’s close to me, so I’m there most years. It gets plugged a lot on The Worldshapers, ’cause I’ve asked a number of writers to be on after I saw them at When Words Collide.

Well, if I can make it next year, I certainly will. I had a great time there.

And I guess this is a good place to mention to those interested that the website for that is WhenWordsCollide.org. It does fill up every year, so if you’re interested in going, it wouldn’t hurt to to sign up for next year, right now. But enough about that, let’s talk about you! I always start by taking guests back into the mists of time, and for you and me, it’s roughly the same amount of mists, to find out, first of all, when you became interested in writing, and when you became interested in writing science fiction. I’ve seen from other interviews that you started writing pretty early.

Yes. I still have some of the things that I wrote when I was, like, five. They are hiding in my parents’ house and I hope they will never see the light of day. The first thing…I can remember writing what would be called fanfic these days, which was in my time based on The Man from U.N.C.L.E.—which tells how old I was—and me and my friends were spies: the standard thing that one writes when one is…I guess I was twele at the time…and I kept writing some of that for a while.

I wrote several plays when I was in high school, but I really got serious in my first year of university. I was in co-op at the University of Waterloo, and there the co-op program is sort of four months in school, then four months in work placement, and I was working for IBM in Toronto, where I knew no one, and didn’t have a whole lot of money. But writing was cheap. So, for four months on my work term in Toronto, I amused myself by writing science fiction. And none of that was saleable, but bit by bit, I got better.

Well, I think it’s come up a few times on here with different authors, the famous saying…I always attribute it to Stephen King, that you had to write half a million words of unpublishable stuff before you wrote anything publishable, but then somebody recently who’d met Ray Bradbury said that he used to say 800,000 words.

Yeah, yeah. A whole bunch of junk before you get down to the good stuff underneath.

Yeah, that’s what it boils down to. So, you got your bachelor’s and master’s in math, but you never actually used that? You went straight into writing? Or what happened after you graduated?

I went…for two years after I got my master’s, I tried to write something significant. I was working on a novel…and I still like the idea for the novel, I might…every now and then, I think, “Is it time to write that? Maybe. Probably not yet.” But for two years I tried to make a living writing while tutoring calculus. That was my income. And at the same time, I was also writing for a musical comedy review at the university, and someone who was associated with that show put me in contact with a group in the computer science department who wanted someone to write computer manuals for them. So, I got a job half-time writing computer manuals, and that kept me in money for long enough for me to start selling stories and things.

Well, it’s interesting, because when I decided to be a full-time writer, one of the things that got me going was there was a market for, you know, general computer books at the time. So, people ask me what my first book is, and I always say, well, my first book was actually Using Microsoft publisher for Windows 95. And my second book was the sequel, Using Microsoft Publisher for Windows 97.

Ah! I have a few Unix books out there that I, you know, they’re on the shelf, but I’m not proud of them.

Well, I was never that technical, but at the time there was actually a market at the level of, “To open a file, click FILE>OPEN.” That’s the kind of level I was writing at. And I was interested, too, that you wrote plays and this musical comedy revue…

Right.

…because that’s another side of what I do. I’m an actor and singer and performer, and I’ve done…I’ve written plays, as well. And I like to ask the writers who have done that sort of thing, if you find your theater background helps in the writing of fiction. For me, it feels that it does. But I’m always interested to see if others have the same experience.

Oh, yes, immensely. So, I did…first of all, this onstage musical comedy thing, and then a group of us who helped write for that started writing straight-up plays and radio dramas. And sometime in there, I got into improv and took a number of improv classes. And all those things go together into…theater gives you immediate feedback on whether your writing works or not, by the amount you cringe when you hear your lines being said. You learn a bit on fool-proofing dialogue. And certainly, improv gives you some good practice in structuring scenes and figuring out how actions go together to make plot.

I often feel that, having directed plays and stuff like that, I feel like I have a very solid image in my head at all times of where characters are in relationship to each other in the space in which the scene is happening, and when I tutor younger or beginning writers—and I’m writer-in-residence at the Saskatoon Public Library right now—I’ve done quite a bit of that—and one thing I often find is, it’s like a gray fog in which everything is happening.

Yes.

And I’m not entirely certain where everybody is in relationship to each other. You get an image of them in one place and the next thing you know, they’re looking out the window, but they never left the fireplace in your head.

Yeah. Yeah.

I think theater helps with that.

Yeah. Certainly, just plain old scene choreography helps. Theatre contributes to that a lot. As you say, who’s where and what’s actually there. The idea of what is in the room besides the characters is hugely useful when you’re trying to figure out what the characters do in response to some problem. There’s almost always something in the room that they can use, if you’ve envisioned the room well enough to actually have stuff there.

And if you plant it in the right place and in the story so it doesn’t materialize out of thin air.

Yes. Well, you know, whenever you write a story, every scene has to take place someplace. Every time someone goes into a room, you pretty much have to describe the room and you want to describe interesting things in the room, and just that description, first of all, trying to come up with something that is interesting and not the same old, same old, will give you material to use later on in the scene.

What you said about fool-proofing dialogue is actually something that Orson Scott Card said when I interviewed him for The Worldshapers, and he’s done a lot of theatre, and he actually had a role in your breaking in, didn’t he? Because he was at Clarion West when you were there?

Yes. He was the first teacher in my year at Clarion West. He gave me really good feedback on a story that he liked a great deal, and that was actually my first published story. He put in a good word for me with the editor of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and so when I sent that story to the editor, it sold, and that was my first pro SF sale.

Before you went to Clarion, had you taken any other formal writing training?

Yeah. Between…the summer of when I got my bachelor’s, I went to Banff, the Banff Centre for Fine Arts, and took a writing course there. W.O. Mitchell was the grandfather of it all, but it was…Alice Munro was there, so, you know, hanging out with some pretty impressive people, and got a lot of good feedback on my writing and how to set about writing stories.

So, I ask science fiction fantasy writers about their formal training…now clearly, at Clarion, science fiction and fantasy is what people are writing, but usually in other writing programs it is not, and there’s sometimes a…

Right.

Sometimes it’s not a comfortable fit with what the program is about. Did you find that, or did it or did you find it helpful that it wasn’t science-fiction focused?

Yeah, I don’t think I wrote a great deal of science-fiction content while I was at Banff. It was mostly…the method, what W.O. Mitchell called “Mitchell’s messy method,” was just sitting down and seeing what spontaneously arose as you were at the typewriter. And at that point, I was writing a lot of memoir-type things, as opposed to actual fiction, and finding what inside of me wanted to be written was very useful for that. The real trick after that is figuring out how to shape that material into actual stories. And once I got started with that, kind of marrying my own memories with science fiction was kind of fun and useful.

Was Mitchell there when you were there?

Oh, yes.

The reason I ask is because W.O. Mitchell is famously from Weyburn, Saskatchewan, which is where I grew up, and I got to meet him once when he came doing a reading for his book, Roses Are Difficult Here, I think is what it was, when I was at the newspaper down there. He was an interesting guy.

Yeah, he’s a fun guy, and, of course, a great raconteur, or was, so he was great to have in classes. And we all had, I think, a fifteen-minute session with all of the writers in residence. It was, you know, in some sense similar to Clarion, in that the writers were brought in for, I think, four or five days, and each of the students had a chance to show the writers their stuff and get some feedback on it.

The other thing I like to mention about Mitchell is that, when I did see him in Weyburn, there was a woman there named Sadie Bowerman, who was the first white baby to be born in Weyburn, she was still alive then. And she’d been his schoolteacher, and she got after him—she must have been in her eighties by then—she got after him for using bad language. So, writers can relate. You never know who’s going to pop up out of your past.

That’s right. I have a few English teachers who have caught up with me over the years and, you know, kind of patted me on the back. And again, some of them have chided me for using bad language.

The other thing I want to mention about Weyburn, Saskatchewan, is that Guy Gavriel Kay was born in Weyburn, Saskatchewan, so Weyburn is a very important place in the tapestry of…well, much more for him than me, I wasn’t born there, but I grew up there.

A hotbed of literature.

Yeah, exactly. Well, you started with short fiction. Did you write that exclusively for a while, or did you immediately try to write novels, or how did that work for you?

Well, I think I wrote a novel…back when I was in high school, I got pneumonia the year after…sorry, the summer after…I graduated, and was basically locked in the house for the entire summer and spent some time writing a novel-like thing. I wouldn’t call it a novel, but it was a long piece of fiction. So…gee, I forget about doing that. I always think that my writing started when I was in university co-op, but no, that summer where I had nothing else to do. But that was kind of an amusement more than a, “Yes, I’m going to be a writer.”

Still, part of your half a million words that you had to…

That’s right. Yeah. Never gonna rewrite that one. That was self-indulgent, as only high-school students can be.

Yeah. So, when did your first novel come along?

My…so, I wrote it…I wrote several novels before I actually published something. So, I was in Clarion in ’89 and was writing short stories and started a novel sometime after that. And I think there were two novels that didn’t go anywhere—and thank heavens they never saw the light of day—before I wrote Expendable, which was published in ’97.

And so now we’re up to how many novels?

Ten, eleven. I guess it’s eleven now.

Are you still writing a lot of short fiction?

Off and on. I can write novels for two or three hours a day, at least the first early drafts of novels, and that gives…so I write in the morning, and in the afternoon, I want to write something different. So, I sometimes write short fiction. Sometimes I write the gaming material that you mentioned in my biography. Sometimes I do freelance editing jobs for various people. So, afternoons I have several hours when I do something besides the novel in progress, and short stories are one of the things I do then.

Okay, well, that’s kind of getting us into the process part of this of the podcast, which is what I’m going to focus on next. So, let’s move on to that. So, we’re gonna focus on All Those Explosions were Someone Else’s Fault, just as an example of your creative process, and see how that ties in with the way you write everything, but before we do that…I have not finished the book; very much enjoying it, it’s a lot of fun…

Thank you!

So, perhaps you can give a synopsis for those who have not read it, without giving away anything that I haven’t read yet.

Ok. Well, the setup is that in the early 1980s, vampires, werewolves, demons, et cetera, come out of the closet and basically say, “Why have we been keeping ourselves secret? We have a saleable asset here. You want to be one of us, pay us $10 million and we’ll make you a vampire or a werewolf or a demon.” And within twenty years, all the movers and shakers, or the wealthy, influential people, are basically darklings. So…and then in the year 2000, suddenly superheroes start appearing. And so you’ve got this world where the rich one percent are essentially monsters and the ninety-nine percent are protected by the people who were stupid enough to touch the glowing meteor or fall in the vat of weird chemicals, or were just, you know, born as mutants. And so, the background setup is the dark one percent versus the super ninety-nine percent, or the supers who represent the ninety-nine percent, who protect them.

And then the story follows four science students at the University of Waterloo who get into a weird lab accident and gain superpowers and become involved in the shenanigans that were responsible for the lab accident. And a supervillain is part of it all, and a cabal of darklings who are up to no good, and the whole thing takes place in something like nine hours on the night of the winter solstice.

And it’s a humorous novel.

Yes, it is. It’s done for laughs. It could…the setup could get very dire with horrible people running the world, but I like playing it for laughs, and the four characters who get superpowers are all funny in their various ways. The first book is about Kim, who is a geology student who…queer—non-binary, anyway…who has a wry view of the world. The second centers on Jules, who is a wonderful, incautious, brash person, and the plan is for four novels, one on each of the superheroes, having them go through their big life change. I think that a novel should be about a huge moment in a character’s life, and each of the four heroes…I mean, “Hey, you’ve just become super. What does that do to you?” And for each of them, it kind of brings to the fore something that they haven’t dealt with, baggage that they haven’t dealt with. And they’re each going to be forced to confront this stuff that they’ve been ignoring for much of their life and deal with their issues one way or another.

So, what was the seed for this and how does that tie into the way that stories appear for you, in general? I’m trying to avoid saying “Where do you get your ideas?”, but that’s basically the question.

You know, I don’t…the seed was the idea of the superheroes-versus-darkling type things, and the one percent versus the ninety-nine percent, which was relevant at the time I started writing this. You know, it was…the Occupy movement had been taking place. I mean, that’s where I get the one percent versus the ninety-nine percent. And it was a time when the politics of the whole thing was kind of in your face.

And I had also done a lot of roleplaying in various contexts. So, if people are familiar with the White Wolf games, which later became Onyx Path, or were…Onyx Path started writing for the same game lines…you could be a vampire or a werewolf or some other type of creature of the night. And that was one set of roleplaying that I had done, but I’d also done a lot of superhero roleplaying.

And putting them together, as far as I know, had never been done before, but was a really cool idea. As soon as I had the idea, I Googled like mad to see if there was anything like this out there, and there wasn’t. Urban fantasy was big at that point. Superhero fiction was just starting to become more prevalent. One of the things that interests me is that superhero comics have been around for eighty years, but superheroes in prose fiction really hadn’t been done a lot before, say, fifteen years ago? There were a few novelizations of superhero movies, but until…fan fiction for sure and the Marvel superhero movies came out…there hadn’t been a lot of superheroes in prose fiction, but that kind of opened up and now there’s a whole ton of it.

Well, it is an interesting juxtaposition. Certainly, I’ve never encountered the two things put together like that, so it’s very interesting.

Yeah, I hadn’t seen it before. I still haven’t seen it. So, it’s kind of fun to be able to play with that without too much competition.

Now, that’s how this came about. Is that fairly typical of your story generation. Is it basically just ideas bubble up and bounce into each other?

I think I go back to what I said about stories being about some huge pivotal moment in a character’s life. So, whatever the seed for a story is, the next thing I want to know is what character is going to experience the setup and what sort of transition are they going to go through. So, often I think of some dramatic situation, some sort of ticking bomb that is going to cause trouble in some setting. But then immediately I say, “OK, well, what character is going to face this problem and what is it going to put them in?” When I was…you told me ahead of time that we were going to be talking about All Those Explosions, and I went back through my notes, and…on the book as I was developing it…and it’s constantly, “What problem is this going to cause for the characters and what sort of transitions are they going to go through because of it?”

Well, and that’s the very next question. What does your planning process look like once you had this idea? It sounds like the characters come perhaps even before you have the plot worked out?

Absolutely. So, it’s useful to have some sort of background problem that is going to force the characters to act—a ticking bomb, so that even if the characters are, you know, lost, or I’m lost because I don’t know what happens next, there’s going to be some pressure to deal with the situation. But I think a novel is about an overt exterior situation, but it also has to be about a character facing some sort of crisis in their life, so constantly, when I develop things, I’m thinking, “OK, what is this going to put the character through? What is the next thing? How are the screws going to tighten on the character?” Not just in terms of the urgency of the external situation, but the development of the internal situation, too.

So, how do you find those characters? How do you decide what your characters are going to be? I mean, Kim is, in her own words, I believe, a “short, queer Asian kid.”

Yeah.

Which, you know, is not you. So…

That’s right.

How did you decide?

Really…so, the first time I…the first draft…Kim was Asian, but not queer. And, she…the situation…so, for people who haven’t read the book, one of the first things she does is, she comes across an old flame of hers, someone she knew in high school. Really, her first serious boyfriend, who has become a darkling, who was always a rich kid who knew he was going to be a darkling as soon as he was old enough to be transformed. And that relationship went bad, and basically, the…Kim was a bland character who didn’t have a whole lot of personality. And one thing I often do when I’m trying to get a handle on characters, especially when trying to get a handle on personality, is sit down and improv stuff in their tone of voice—just sit at the typewriter…or the computer, of course, these days…and write a diatribe from them as fast as I can and see what just pops out. So, this is Mitchell’s messy method again, just sitting down and blast it out and see what pops out. And Kim’s queerness came from that. I was blasting away, basically a monologue, and it just completely took me by surprise when she started talking about, “No, I’m not as binary as you think,” sort of thing.

And there were several days there when I thought, “Oh, shit. Am I going to actually write a non-binary character?”, you know, a straight middle-aged white guy writing a queer young university-age Asian. Did I have the nerve to do that, and how much homework would I have to do in order to not be that guy writing someone who I had no right to write? But that’s what was…that was the voice that came to me, and eventually I said, “Yeah, OK, I’ve got to go with this.”

Well, she is a very interesting voice.

Yeah. Yeah. And once I had that handle on the character, a whole lot of things came out and the character came alive, and some of the situations that were dead on the page in the first draft took on a whole different character and really much more interesting resonance than they had been in the first draft.

Did you do something similar with your other main characters?

Yeah. So, Nicholas had the same process. I did, you know, a soliloquy from his point of view, and not so much with the other three superheroes, because I knew their books were going to be coming along later. When I did the Jules book, which is They Promised Me the Gun Wasn’t Loaded, the sequel to All Those Explosions, I did do soliloquies from her point of view. And for the future books, I will be doing the same thing. It’s just a really useful way to unlock what inhibitions have been keeping…holding me back from doing, going as far as I need to for a character.

Once you’ve developed the character, you have an idea for the setup, how much of an outline or planning do you do? Is it a very detailed? Are you a pantser or a plotter?

I’m mostly a pantser, but especially because I’m writing superhero things, I want there to be some great set pieces. So, I plan for interesting places where big superhero action can take place. So, in All Those Explosions, there are several big superhero-vs.-monster action things, and I figured out where they were going to take place and sort of some context for why they were happening, and an overarching plot for them.

So, in All Those Explosions…well, Waterloo has a number of tourist attractions and I want, over the course of the series, to destroy them all. So, in the first book, I trash the Waterloo market, which is the St. Jacob’s Market, which is a big farmer’s market. In the second one, I trash a popular club, the Transylvania Club, which is just, you know, a name like that is asking to be associated with monsters. And the third one, Waterloo has a clay and glass gallery, the National Clay and Glass Gallery.

Oooh!

I mean, I got to have a fight there. And Clay and Glass is right next to the Perimeter Institute, which is an institute of theoretical physics, a kind of a world-class physics research center. So, trashing both the Clay and Glass and Perimeter is kind of a gimme. And I don’t know what I’m going to trash for the final book, but we’ll see.

There is some fun to that. The last book in my young adult series, The Shards of Excalibur, the final big climactic battle takes place at a provincial park called Cannington Manor. I do a pretty good job on it, too.

Yeah, I mean, if you’re going to take a place…if you’re going to have your story take place in a real location, then let’s make use of the location. And especially with, you know, if you’re going to have superheroes, there is going to be a large set of smoking rubble.

And I still remember the Jim Butcher, I don’t remember which book it was, in the Dresden Files, where Sue the Tyrannosaurus comes to life.

Yeah, a super thing. I just loved that episode. Yeah, I don’t remember which book it was, but…

So, you talked a little bit about your actual writing process, you know, three hours in the morning and work on other things in the afternoon. Do you just work at home, are you a go-out-to-a-coffee-shop guy? I gather you type and don’t do it longhand or anything like that…

Oh, I do some things in longhand. If a particular scene is not working out well, I go longhand and I write it out. I’m working right now on a haunted-house novel, and this morning I spent writing really the first scene of a particular character, because I really wanted to slow down and cover the bases and really get the character’s voice down on the page. So, when I want to…writing fast is useful, but writing slow is also useful.

Well, then, speaking of that, are you a fast writer or a slow writer when you average the two things together?

I’m not superfast. I can I usually do about a thousand words a day. So, you know, some people do a lot more than that, several thousand words a day, and I’ve done that, but usually, a thousand is good. And that’s for my morning stuff. In the afternoon. I would do maybe the same amount again, depending on whether I’m writing new stuff or revising old stuff.

When you get to the end, you have a draft, have you done sort of rolling revisions, so it’s pretty clean at that point, or do you go back and do a complete rewrite, or how does that work for you?

I do some rolling revisions, but usually I have to go back and do several more drafts. So, as I say, I’m mostly a pantser for the first draft, which means that there’s rough-around-the-edges stuff. So, the haunted-house novel, which is the one I’m thinking of, the rough draft ending was really, “Yeah, OK, I’m gonna keep writing it, but I doubt that I’m going to keep any of it.” The second draft is pretty good. I like the action of the ending, except that the precipitating incident…so, there’s something that makes all hell break loose, and I like the hell that breaks loose, but I’m not so crazy about what actually kicks things off. So, I’m going to at least have to rewrite that again, which will probably necessitate a few other changes. So, I’m refining things as I go along and I hope it’s no more than three drafts, but…that’s about typical for what I’m doing.

You’ve been published by various publishers, which means you’ve worked with a lot of different editors. What typically comes back to you from editors to work on? If anything.

I don’t get a whole lot of structural stuff. It’s mostly cosmetic or, you know, “I didn’t understand this,” or, “This chapter is slow,” or something like that. So, I don’t get…once or twice. I’ve had people, an editor, say, “No, this ending just doesn’t work.” But mostly it’s, “I didn’t understand their motivation for doing this,” or, you know, “Polish up this section again.” So, I’m pretty lucky, in that I want a story to be as clean as possible before I send it to my agent. And she makes a few comments, but not many, and then she sends it off. So, I like things being pretty good to go before I send them out, which means I have to spend a fair length of time…I don’t send out anything that I don’t think is pretty good already.

Now, you do some editing for other people. Do you find that working on other people’s manuscripts helps you when it comes time to look at your own?

Oh, sure. It’s much easier to see problems when other people have them, but I know I have the same thing, so…and, you know, we all have words that we overuse—“really,” “quite,” “very,” all that. And as I’m reading somebody else’s stuff…I have a list of these words that I overuse, and reading somebody else’s stuff, I, you know. “Oh, yeah. There’s one of mine that I should pay attention to, too.”

Speaking of which, brilliant little thing from Brandon Sanderson that I recently heard about in their Writing Excuses podcast is to, you know, you have your list of words that you overuse or, you know…”suddenly,” there’s another one that is real easy to use too much of…just do a global replace on the word with brackets around it, square brackets, and that makes it stand out. So, when you’re reading the book, reading the manuscript, you see these things and you could say, “Do I really need that?” It really draws your attention to the words that you overuse and gets you…makes you think about them again. I really love that technique and I use it now.

Oh, yeah. That’s a good one. I think I’ll have to adopt that, too.

Yeah. Yeah. It just draws your attention to something. Sometimes “very” is a perfectly good word to use, and a lot of times the prose is stronger by crossing it out, by deleting it.

I find that my characters tend to use animal noises too much in dialogue, they growl things and snarl things and…

Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. That’s a good point.

I do avoid hissed dialogue because it always bothers me when somebody hisses something that has no sibilance in it.

Generally speaking, I only let myself use “said,” “told,” “replied,” “shouted,” “whispered,” maybe a “muttered” or two…oh, and “asked.” But I do try to avoid the animal noises and so on.

Yeah, I’m aware of it, but that doesn’t mean I catch it all the time. The other thing is…you’ve probably had this experience, too…the best way to find things that you overlooked is to read your work out loud in front of an audience after it’s been published.

Yeah. Yeah. Zadie Smith has a quote, something to the effect of, “The best time to rewrite your stuff is two years after it’s been published and ten minutes before you read it at a literary festival.”

That’s about right. Well, we’ve got about ten minutes left, so I want to get to the big philosophical questions.

Sure.

It’s really one question with multiple parts. Why do you write? Why do you write this stuff? And why do you think any of us do? That’s really three questions. But it’s kind of one.

Oh, well, just like almost every other writer I write because I can’t not write. These days I get up in the morning and write, and I write to understand what’s in my head and to…because I like writing stories.

Why do I write something in particular? Because something about the idea has got its claws in me, and the only way to get free of it is to write it and write it well. So, this…again, the haunted-house story that I’m thinking of was an idea I had probably two and a half years ago. And I had no idea why I wanted to write a haunted-house story, and it’s taken me two years to crystallize what I want to say in the book and why I’m writing it.

I think…writers, as you know, sit alone for hours at a time. And what we write today will not be seen in the world for a long, long time. It’s, you know…it takes me at least a year to write a novel, often more, and after it’s written, it’ll take at least another year before it gets out for anyone to…before it gets published…and so you really have to be obsessed and in the moment to write. There has to be some sort of reward or compulsion to write, because you don’t get the fame and fortune, if ever…

I’m still waiting for that.

Yeah. Yeah. Well, in some sense, we all write to impress someone. Paul Simon said, when someone asked him why he wrote songs, “I write songs to impress girls.” And, you know, there is that aspect…

I went into theater to kiss girls.

Yeah. Yeah. And I certainly started writing to, you know, let’s impress women. But it’s a long time before that happens. I mean, a long time between sitting down to write the sentences today and before anyone is impressed by it. And I am not, you know, making a gazillion dollars or having a gazillion readers. I’d love to. So, you just kind of get the rewards, and every now and then you have a character suddenly come to life, like Kim revealing that she’s queer, and the idea that you…every once in a while, you feel as if you are telling a truth that is out there, as opposed to stuff that you’re just pulling out of your head. And it’s really cool when that happens.

The podcast is called The Worldshapers. Probably a bit grand to talk about shaping the world through fiction, but what do you hope your writing does for the readers who read it? Because you can certainly influence individuals as they read your stories.

Yeah. Well, for All Those Explosions, I wanted to make people laugh, and…

Works for me!

Good, thank you! And to have the fun that I find in superheroes. I started reading superhero comics when I was just a kid. I talked about this at When Words Collide, that my great uncle would buy me one comic book a week when I was seven years old and I bought comic books and I bought superhero comic books. And I do not know anymore any of the people that I knew when I was seven, other than my immediate family, and I still know Batman, I still know Spider-Man, I still know all of those characters that I knew back then. I keep up with them. I don’t know the people anymore, but I know the characters. And so, to be able to write superheroes…not, alas, Marvel and DC superheroes, although, if anybody from Marvel or DC are listening, I’m there, hire me!…but to be able to write superheroes and just have fun with them…I hoped that I could pass on the delight that I get from superheroes to other people, too, and to share in the joy.

And for other books, it’s almost always the same, that I get delight from various types of stories. And so, I want to be part of that conversation, be part of the fun or the delight or the concern or the thrills or the horrors or whatever. It’s such a delight to be a writer and to be part of the conversation.

That’s actually what I always say, that I started writing because I loved the stories that I was experiencing so much, I wanted to be able to create stories that other people would enjoy as much as I enjoyed the ones I’ve been reading. So, that’s probably a very common thing with writers.

Look at fanfic! I think many people get their starts in fanfic, if not actual…these days, you can actually put it in front of the public, but even if you don’t, you write your little stories and show it to your friends and so on. And that’s because whatever you’re doing fanfic of touched something in you and you want to be in that world, you want to have a piece of it, too.

You mentioned what you’re working on, the haunted-house novel, anything else that you’re working on right now?

I’m doing a re-imagining of Sleeping Beauty where nobody is stupid. It’s kind of fun to write a fairy tale with sensible people. There’s a lot of re-imagined fairy tales these days. Naomi Novik immediately comes to mind, but other people have been doing it, too. And it’s fun to write fairy tales which have that feel of depth, mythological depth, folkloric depth, but bring a modern sensibility to them that…there are just some strange things that happen in very tales that are hard to believe, and trying to justify them—or not!—Is fun.

And where can people find you online?

I am…most of my stuff is on Twitter @jamesagard. I do Twitter every day. I also have jamesalangardner.com, which I blog at occasionally. Those are the best places. I do have a Facebook page, which I almost never do anything with, so…

Well, I think that’s about the end of our time. Thanks so much for being a guest on The Worldshapers!

It was great talking to you, Edward. Thanks for having me.