Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

An hour-plus chat with author, editor, screenwriter, and award-winning essayist David Boop.

.Websites

davidboop.com

longshot-productions.net

Facebook

@dboop.updates

Twitter

@david-boop

David Boop is a Denver-based speculative fiction author and editor. He’s also an award-winning essayist and screenwriter. Before turning to fiction, David worked as a DJ, film critic, journalist, and actor. As Editor-in-Chief at IntraDenver.net, David’s team was on the ground at Columbine, making them the only internet newspaper to cover the tragedy. That year, they won an award for excellence from the Colorado Press Association for their design and coverage.

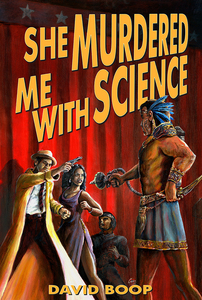

David’s debut novel is the sci-fi/noir She Murdered Me with Science from WordFire Press. A second novel, The Soul Changers, is a serialized Victorian Horror novel set in Pinnacle Entertainment’s world of Rippers Resurrected.

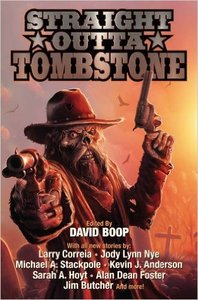

David was editor on the bestselling and award-nominated weird western anthology series, Straight Outta Tombstone, Straight Outta Deadwood, and Straight Outta Dodge City, for Baen. He’s currently working on a trio of Space Western anthologies for Baen starting with Gunfight on Europa Station.

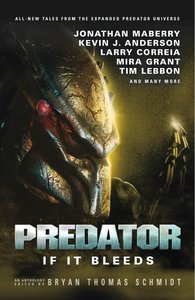

David is prolific in short fiction, with many short stories and two short films to his credit. He’s published across several genres, including media tie-ins for Predator (nominated for the 2018 Scribe Award), The Green Hornet, The Black Bat and Veronica Mars.

Additionally, he does a flash fiction mystery series on Gumshoereview.com called The Trace Walker Temporary Mysteries (the first collection is available now.) He does a quarterly comic strip about a new author’s experiences with Sign Here, Please, and runs an author-themed t-shirt shop called Author-Centric Designs by Longshot Productions.

David works in game design, as well. He’s written for the Savage Worlds RPG for their Flash Gordon (nominated for an Origins Award) and Deadlands: Noir titles.

He’s a Summa Cum Laude Graduate from UC-Denver in the Creative Writing program. He temps, collects Funko Pops, and is a believer. His hobbies include film noir, anime, the Blues and History.