Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

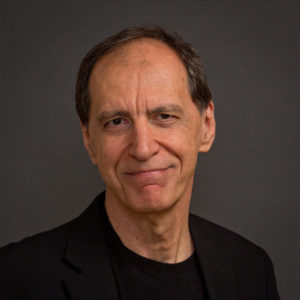

An hour-long conversation with John Kessel, author of Pride and Prometheus, The Moon and the Other (both from Saga Press) and other novels, and, as a short-fiction writer, winner of two Nebula Awards, the Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award, the Locus Award, the James Tiptree Jr. Award, and the Shirley Jackson Award.

Website

johnjosephkessel.wixsite.com/kessel-website

Facebook

www.facebook.com/john.kessel3

The Introduction

John Kessel‘s most recent book is the 2018 novel Pride and Prometheus, published by Saga Press. He’s the author of the earlier novels The Moon and the Other, Good News from Outer Space, and Corrupting Dr. Nice, and, in collaboration with James Patrick Kelly, Freedom Beach. His short-story collections are Meeting in Infinity, a New York Times notable book, The Pure Product, and The Baum Plan for Financial Independence and Other Stories

His stories have twice received the Nebula Award, given by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, in addition to the Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award, the Locus Award, and the James Tiptree Jr. Award. His play Faust Feathers won the Paul Green Playwrights Prize, and his story “A Clean Escape” was adapted as an episode of the ABC TV series Masters of Science Fiction. In 2009, his story Pride and Prometheus, on which the novel was based, received both the Nebula Award and the Shirley Jackson Award. With James Patrick Kelly, he has edited five anthologies of stories revisiting contemporary short SF, most recently Digital Rapture: The Singularity Anthology.

Born in Buffalo, New York, Kessel holds a B.A. in Physics and English and a Ph.D. in American Literature. He helped found and served as the first director of the MFA program in creative writing at North Carolina State University, where he has taught since 1982. He and his wife, the novelist Therese Anne Fowler, live and work in Raleigh, North Carolina.

The (Lightly Edited) Transcript

So, welcome to The Worldshapers, John.

Thank you. Glad to be here.

Now, we’ve never met in person, but the way you ended up on this show…I’ve been aware of your name for a long time, obviously, with your record, and being in the field, but I’d never run across you at a convention or anything like that. But Christopher Ruocchio, who was a guest on the program a little while ago, was one of your students, and he mentioned your name. And I thought, “You know, I should have him on.”

Well, I’m glad you had him on. You know, Christopher seems to be well-launched now with his first novel. I guess the second novel in that series is coming out, is that right?

Yeah. Just came out. And he’s a fellow DAW Books author, so I’d met him at a DAW dinner at WorldCon last year. That’s how we made that connection. In this field, you know, you sort of, you know somebody, then they know somebody…everybody’s connected

Even though it’s much bigger than it was when I started, it’s still a fairly small pond, and you will run into people, and everyone eventually knows everyone else in some connection.

Yep.. Well, we’ll start the way I always start, which is by taking you back into the mists of time to find out how you became interested in science fiction and fantasy and specifically in writing it. Most of us, it starts with reading as kids. Is that how it worked out for you?

Pretty much, yes. I was reading science fiction and fantasy…really from, it seems like, from the beginning. I cannot remember the first book I ever read that was science fiction. There were children’s books–and I was born a long time ago, I was born in 1950, so we’re talking, you know, late ’50s, early ’60s, I was definitely already hooked on science fiction and fantasy. I liked fairy tales an awful lot, and then I somehow, you know, I went to the library and got books from the science fiction section of the library.

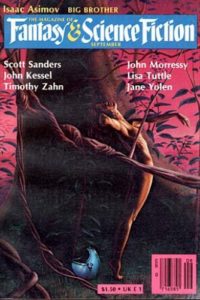

And back then, they had…a number of publishers had fairly serious attempts to write, publish, YA science fiction, and Robert Heinlein wrote a series of juvenile novels that I really snapped up. And also André Norton, who was Alice Mary Norton, wrote a whole series of YA science fiction novels that I loved. It was quite a shock to me when I discovered that Andre Norton was a woman. It was years later. And then around…I think it was 1963 exactly…I pretty much know exactly when it was…I was at my grandfather’s house on a Sunday, and I had had my library book there and I finished it and I had nothing else to read, and I was bored, and I asked if I could go down the block–this was in Buffalo, New York–to see if I could buy some comic books. And they said, “okay,” and so I walked down to this delicatessen, Cosentino’s Delicatessen, and they had some comic books, but they also had science fiction magazines, which I had never seen. I knew they existed, but I had never seen one. And immediately I bought my first science fiction magazines, and then I was well and truly hooked, pretty much. I had subscriptions to Galaxy and Fantasy & Science Fiction and Analog starting in the early ’60s, so I was really much a pretty much a science fiction nerd from day one.

Well, it’s interesting, because—I’m a little bit younger than you, I was born in ’59–but that’s exactly my list of books that got me interested in it, Heinlein and Andre Norton. Somehow I knew Andre Norton was a woman. I don’t know remember ever being surprised to find it out. So I must have read a bio or something of her early on.

I think it became much more public knowledge by the late ’60s, but up until the mid-’60s, I think, you know, she basically kept her identity close to the best.

There was James Tiptree, Jr. I was surprised to find…

Yes. Right. Me too, really. Yeah.

Well, by the time I was reading it would’ve been the late ’60s, so that’s probably why I knew it from the beginning. But that’s sort of the same list of things that I became interested in as well. So, when did you start trying your hand at writing?

Well, you know, I often tell students, my writing students, that one of the seven warning signs that you might become a writer is that you are writing fiction which is not on command by your English teacher before the age of ten, and indeed, I was writing stories and I actually made a little magazine, I would compel my friends to write them and I would illustrate stories myself, probably…maybe I was eleven or twelve. And so, I was trying to do that, and I remember there was a contest in Fantasy & Science Fiction in the mid-’60s that asked for submissions, and I submitted an entry there and I got my first rejection slip and I still have it. And so, I was at it pretty early.

I was, you know, in my early teens when I submitted my first story. I didn’t ever submit another story until I was in college. But, you know, I really…I knew that there was the possibility of an ordinary person writing stories and sending them off. And it was really quite…I was felt empowered by the fact that they had sent me a rejection slip. The idea that I, you know, John Kessel, a kid from Buffalo, New York, could write a story and send it into the magazine and they would read it and say “No,” but they would send me a slip, just as if I were, you know, a published writer. And so, that was cool.

Yeah, I remember that that same feeling. My first published story, though, was actually…at about that age…I actually got a story published in something called Young Authors’ Open in Cat Fancy Magazine.

Wow, good for you.

It was a terrible, terrible pun about Santa Claus looking for a replacement, and he searched the world over, and he found this guy he thought was perfect, but the guy wouldn’t weed his garden and he knew he couldn’t be Santa Claus because he wouldn’t hoe-hoe-hoe. That was the…

Well, you know, it’s funny because my first submission to F&SF was what was called a Feghoot and it involved a pun.

Oh, I remember those.

Yeah.

So, were you focused on short fiction entirely? Did you try your hand at longer stuff during those years, or…?

Pretty much short fiction. I really loved short stories–still do! And so, that was my thing, was short fiction. Although I read a lot of novels, I’d never tried to write one till I was in my twenties, late twenties, and really had to learn…I mean, novels are different from short stories. And I don’t think the short story is a less important form, although, you know, in terms of making a living, certainly it’s hard to do writing short fiction. But I think artistically the short story is a beautiful form. And it’s not a practice for the novel, it’s not a less worthy or less important form, but it is different.

Somewhere on my bookshelf right behind me, I was just turning around to look, is a collection of science fiction short stories , one of those anthologies from the late ’50s, early ’60s. And, yeah, short fiction was sort of my introduction to it, and that’s sort of the way I started writing it as well. But it turns out I more of a novelist, I think, than a short story writer. Did you show your stories? You said you had this little magazine. Were you letting people read your stories?

You know, in a way, my friends were not as interested in this as I was. So, you know, it was just my thing, at that stage anyway, when I’m talking about junior high school or middle school. So, no, I didn’t. I didn’t really advertise them to people.

I usually ask that because when I’m teaching writing, and I know you’re much more of a writing teacher than I am, but I often recommend to people that they do let other people read their work because it’s a way to find out if you can tell stories that people are interested in.

Well, I think ultimately you do have to submit the story to an audience, either an audience of, you know, a teacher or mentor, or other writers. And so, I’ve actually been very active in workshopping. I like workshopping, and not just as a teacher in the university, but…I went, I was invited to, one of the last Milford workshops, run by Ed Bryant, in 1980 and then again in ’81. That was a real revelatory experience for me in 1980 because I met these other writers, many, many of them up-and-coming writers, but also they were, most of them, unknown. I mean, among the writers who were at this first workshop I went to were Ed Bryant, who was well-established at that point and was sort of a writing hero of mine, although people don’t remember him anymore.

I remember the name.

But then, Connie Willis was there, she had only published a few stories. Cynthia Felice. One of the other people that who had not published a single story at that point, who was one of the workshop members, was Dan Simmons. And George R.R. Martin was one of the writers there. So, I got to know these people really early, and it was really heartening that they would read my stories and give me critiques, so that was good.

Well, when you went to university…where did you go to university?

I went as an undergraduate to the University of Rochester in Rochester, New York. It’s a small private school. And I studied astrophysics, I wanted to be an astronomer. And then I double majored. By the time I graduated, it was a degree in physics and English.

What drew you out of astrophysics to add the English?

Probably you could say that tensor calculus had something to do with it. I could do the math pretty well through the first couple of years, but by the time I got to the really higher math, and the higher physics, too, it’s tremendously mathematical. It especially was at that time, where I think the slogan was, you know, “Shut up and calculate” in physics. And so, I could…I had to struggle to do that, the really advanced math. And I could see other physics majors around me, and they were very…it was a small group of physics majors, maybe there were…I think there were twenty in my graduating class…some of them could do it much better and with more facility, more naturally, than I could. So…and I also saw that my GPA in English classes, which I was taking for fun, was like a grade-point higher than my math class. Great. So, I thought, “Well, and I’m enjoying English classes. I’ll double major.” I didn’t know what exactly I was gonna do at that point, but I know I loved reading and I at that point was starting to write stories again.

And so, I took my first creative writing class in my second semester, senior year at Rochester, and wrote a science fiction story for my final project there. And so, I was getting more serious about that. And then I went to graduate school at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, Kansas. And the main reason I went there was that there was a science fiction writer on the faculty there, James Gunn, who’s, you know, still alive, ninety-six years old, I believe, and was…he’s a Grand Master of SFWA. And, so, he was my mentor there. I was in his classes and he directed my master’s thesis, which was in fiction writing. And then, on my Ph.D. dissertation, I persuaded the university to let me write a collection of stories, rather than a scholarly work, for my Ph.D. in American Lit, and so I wrote a bunch of stories and he was also on my committee at that point.

Were those science fiction and fantasy stories?

They all were. And one of them in my dissertation was “Another Orphan,” which won the Nebula Award in 1982. So, I guess I, you know, I was glad I was able to do that. I mean, I was writing anyway. I would have written the stories anyway. But it was…I probably wouldn’t have finished my dissertation if I had had to write a scholarly dissertation, because I knew at that point, although I’m very interested in, you know, literary study, and I’ve taught American Lit for thirty, almost forty, years, I really wasn’t interested in writing books about, you know, canonical writers and being a scholar, I wanted to write fiction, so most of my energy went there.

Well, this is…it’s interesting to me that…I ask most authors about their, you know, if they had any formal creative writing training, and you get a really mixed bag with science fiction and fantasy authors. There are some who did it and it was not a particularly good experience for them because they met so much pushback against writing science fiction and fantasy. Fortunately, you found James Gunn.

Right.

Was he the only one teaching at that level at that time?

Well, there were very few. I think the only one I can think of…this is 1972, when I went to grad school…is Jack Williamson, who was teaching, I think, at the University of New Mexico.

Right.

I don’t know if he was a regular faculty member or not, and I didn’t even know he was teaching there. So, the only one I knew about was Gunn, and that’s why I went there. So, I guess you could say that that was instrumental there, that he did not turn up his nose at my writing science fiction. I’m very aware of what you say, that many creative writing teachers, at least in the past, have been very skeptical of anyone who wants to write genre fiction in a, you know, a literary workshop.

Do you think that’s changing?

I think it’s changing to a degree. It depends on what kind of genre fiction you write now. If you write a story with aliens and spaceships and, you know, basically a space opera or that kind of background, in a MFA program, you’ll probably have a hard time unless you go to one of the specialized programs like the Stone Coast Non-Resident MFA, which has people like James Patrick Kelly and Liz Hand and others as teachers. But, I do think there is, you know, there’s a lot more fiction being published now by, we’ll call them mainstream writers, that has fantastic elements in it. I mean, it’s everywhere in our culture now. So…and there, you know, bestselling novels that are written that have time travel in it say or, you know, an apocalyptic plague like Station Eleven, that kills off pretty much everybody. Things that would have been in science fiction novels in 1960 now are published and they’re not really called science fiction, but they have the material of science fiction. They generally treat it a little different than a science fiction writer would, as well. But if you’re going to do spaceships and aliens, then you’re still, I think, going to be put in a different pen.

It’s interesting for me because I’m…I was asked this year to mentor an MFA student from the University of Saskatchewan, the first time I’ve done that, and he’s writing a young adult fantasy novel. So it was…I was pleased, in fact, that the University Saskatchewan didn’t seem to have a problem with people writing in those kinds of genres. And it’s been interesting for me, too.

Well, there are many more professors and teachers in these programs who have genre credentials. So, I think that it is a lot better now than it was in 1972.

So, in between graduating university and starting teaching at North Carolina State University, what were you doing in that interim there?

Well, I finished my coursework for the Ph.D….must have been by ’78 or something like that…and I was supposedly writing a dissertation. Not very fast. I was writing stories. And I took a crack at being a full-time writer and didn’t have much success at it, just writing short stories. So, I got a job at a wire service as an editor. Fortunate to get that. It was a very good job. For three years, I was a copyeditor and then a news editor for a wire service called Commodity News Services out of Kansas City, which was owned by… half-owned by Knight-Ridder newspapers and also by UPI, the United Press International wire service…and I learned an awful lot from that. That was very interesting work. So, that was what I was doing while I was on the side trying to finish my dissertation.

And thenm when I finished it and got my degree in ’81, I looked for a teaching job. Because I found that, as a wire-service editor, it was very high-pressure work, I was editing text all day, and I didn’t feel like writing when I got home. So, I thought, “Well, if I get a teaching job, I can have the summers off at the very least, and my schedule during the week, I won’t have to be sitting in an office from eight to five every day doing high-pressure work. And I was fortunate enough to get the job at N.C. State and I came here in fall of ’82.

And been there ever since.

And been there ever since, yeah. Yeah.

Were your first sales, then, along in their somewhere? Short fiction sales?

So my first fiction sale was in 1975 to an anthology called Black Holes that…they paid me for the story, but it never came out, ’cause the publisher went under. It was…as with so many young writers, often you’re selling to marginal markets. You can’t get into the top paying markets, so you’re just trying to get in somewhere. And that actually happened to my first three stories. I sold them to markets that folded before the stories came out.

It starts to make you a little paranoid.

Yeah, I began to feel pretty discouraged. But then, it was in the late…I think it was in the ’70s, ’77, I sold a story to Galileo, and then I also sold one to Fantasy & Science Fiction, a month apart. And what happened was, a bunch of stories I had written already sold, then, one after another. And so…if I said ’80s earlier, I mean the late ’70s was when I really started to break in. So ’77, ’78, ’79, I started to see stories come out.

And then, of course, you mentioned you won the Nebula in ’82.

Right, which was a huge shock. It was the first time I was nominated, and I was a complete unknown, and I think it was quite shocking to people that I won. And of course, the story was…it showed my background. because it’s a story about…your listeners may not know…it’s about a commodities broker who wakes up on page one and he’s on a sailing ship and he doesn’t know how he got there. And it turns out it’s the Pequod, and he’s in the middle of Moby Dick. And he read it… had to read it in college…and he knows that at the end everybody dies except Ishmael, and he’s not Ishmael. So, that that was my premise, and it used my literary study, ’cause I’m a huge Herman Melville fan, but also it had this sort of fantasy element, and it also used my commodities-editing knowledge, so it really came out of a lot of things that were going on in my life. I wrote it in 1979 and ’80, and it came out in fall of ’82, and won the award in ’83.

You mentioned the commodities feeding into that story? Has your astrophysics background played into any of your science fiction writing over the years?

Certainly I know a lot of astronomy and I try to get the science accurate. I know physics, and I’m not any kind of genius at it, but I know basic physics. And so, when I’m doing science fiction stories, I do try to make it as plausible as I can, but I’m not afraid to violate fundamental laws of nature in order to write a story. And I’m not considered really a techie writer, I think I’m more considered a literary science fiction writer. And then I write stories that I think of as fantasies…and when I say that, everyone thinks, “Oh, it’s like Game of Thrones, castles, dragons, you know, lords and ladies. No. I don’t…I’ve never written a story of that sort in my entire career. What I mean by fantasy is a story that violates reality, has some element of the fantastic in it, could be set in the present, the past, but it’s not explained by an appeal to science.

Well, we’re gonna talk about your creative process using Pride and Prometheus as a sort of a template for how you work. But I also wanted to ask you before we did that about…I noted that you had written a play, Faust Feathers. Have you done other playwriting? I’ve done some playwriting and I’m a professional actor, so I’m always curious about that sort of thing. So, have you done a lot of playwriting?

I have done some playwriting. I wrote a one-act back in the late ’80s called “A Clean Escape,” based on a short story I wrote, that was performed here in Raleigh, and I was very pleased to see that happen. And later on I adapted it for a thing called Seeing Ear Theater, which is an audio play thing run by the Sci-Fi Channel. And then I wrote Faust Feathers, which won the Paul Green Prize, and it got produced somewhere in Nebraska but I never got to see it. And “A Clean Escape” actually eventually got adapted for that show Masters of Science Fiction. So, I have written some plays and I did take an acting class, although…I actually am in a couple movies. I’m in a very low-budget movie called The Delicate Art of the Rifle. I play…it’s kind of typecasting, I play an obnoxious college professor who gets murdered. So, I’ve done a little bit of that stuff. But, you know, mostly I have stuff stuck to prose fiction.

I’m always interested in the crossover between fiction and plays because they are very different kinds of writing. In the play world, of course, it’s very much dialogue driven.

Right. It’s very much that’s the case. But there’s also…when you’re writing, you have to cast yourself into the mind of a character who may not be like you in order to write a book. And it seems to me that’s what actors do. You know, the idea that you’re portraying someone who’s not you, but you have to make their behavior rational and to act in a way that they would act but somehow make it your own. And that, to me is a kind of mental trick that writers do as well as actors.

Yeah, I often make that point when I’m talking to people about the two things. All right, well, let’s move on to Pride and Prometheus. And before we get into talking about how it all came about, and your creative writing process, maybe a synopsis and what the book is. I’ve not quite finished it, but I’ve read most of it.

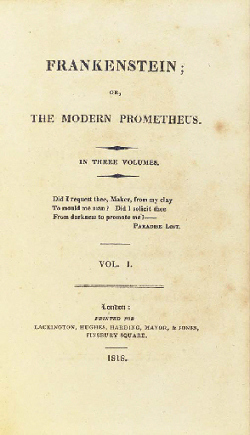

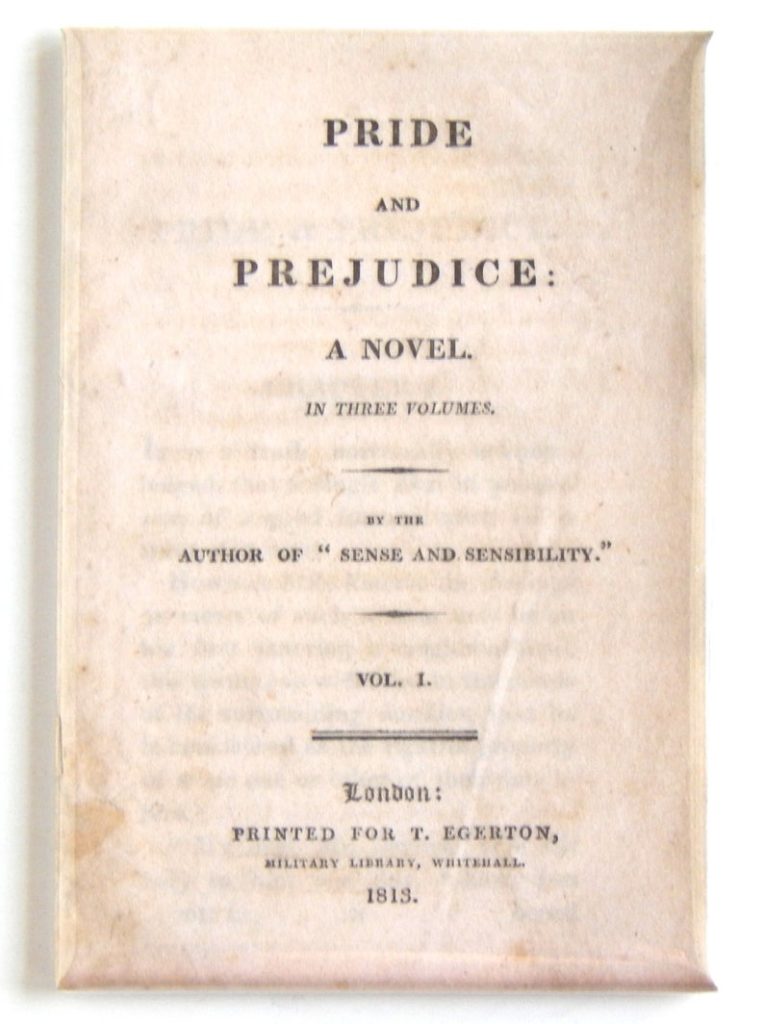

Well, it’s a kind of a crossbreed. I’ve written a number of stories over the course of my career where I’ll use characters or situations created by other authors. “Another Orphan,” which won the Nebula, puts my character into Moby Dick. In this story I’m basically crossing Frankenstein with Jane Austen’s character, from Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. And this kind of story really appeals to me in that, in a way…it’s a way of sort of thinking about the story and the characters, the way maybe a literary critic might do it, but instead of doing it in terms of literary analysis, I just want to see, you know, what sorts of situations would happen. Because…

I got the idea for the story from a workshop where we were reading a story by a writer named Benjamin Rosenbaum, a wonderful writer, who had a story that was a parody of Jane Austen. And it occurred to me, as I was talking about this story there at the workshop, that Jane Austen and Mary Shelley were contemporaries. They were…if you went to a bookstore in 1818 in London, you could find Jane Austen’s novels, Pride and Prejudice, on the shelf next to Frankenstein. And yet they’re very, very different books. And I never, as an English professor, very seldom ever heard anyone talk about Mary Shelley and Jane Austen in the same context. Now, I think they do a lot more, but not back then. And so I thought, “Well, they’re so different.” I mean, you know, putting a Jane Austen character in Frankenstein, that doesn’t work. I mean, that kind of character, what would they do in Frankenstein? And then putting one of, you know, Victor Frankenstein or the monster into a Jane Austen setting, you know, they don’t belong in a ballroom, OK? But that, to me, intrigued me, and so I got carried…and I wrote originally a novelette version of this, I took the character of Mary Bennet from Pride and Prejudice and imagined her a decade or more after the end of that book, and had her meet Victor Frankenstein and eventually meet his monster.

Yeah, and I guess it’s hard to synopses it without sort of…

Oh, well, yeah, it’s…you know, Mary is the…she’s the old-maid character, the middle sister in Pride and Prejudice, who’s really not very attractive. She’s kind of bookish and moralistic, she’s always preaching at people. In Pride and Prejudice, she’s hardly even in the book, and when she’s there, she’s sort of the butt of the joke. She’s the only one of the Bennet sisters who’s not pretty. If you know Jane Austen’s books, they’re almost all about finding the right mate and marrying. And I imagine that Mary is going to have a hard time of that. So, I imagine her as, you know, thirty-two years old and on the brink of old-maid-dom, and she gets dragged to a ball by her mother and her younger sister, Kitty, who’s still trying to get married. And there she meets Victor Frankenstein, who is in England–she doesn’t know this, but–in Frankenstein, Victor goes to England, after he’s created the monster. The monster gets abandoned by him and has a terrible time of it and becomes very alienated, and eventually finds out that Victor created him, and goes to Victor’s home and strangles his younger brother, and then threatens Victor with killing everyone in his family if Victor does not create a mate for him. Since no human being will have anything to do with him, he needs to have someone to give him solace, and so he forces Victor to agree to make a female creature. And so Victor travels to England with his friend Henry–this is all in Frankenstein–and travels around and eventually goes up to Scotland, on an island, to create the female, the bride of the monster.

And so, my story begins where Mary’s at this ball in London and Victor is there with his friend Henry, Henry drags him to the ball, and they dance together and strike up a conversation, and it turns out they like each other. And so, that’s the beginning of it. And the rest of it, it sort of follows Mary’s encounters with Victor. Victor is being tormented by the fact the monster’s following him, and then the monster is desperate to have Victor follow through on his promise. And the story alternates between the points of view of these three characters. It’s mostly Mary’s point of view, but it’s also in Victor’s point of view and also in the monster’s point of view, which, in Frankenstein, that’s true, too, if you’ve read it, both Victor and the creature, his creature get to have their own points of view.

Yes, one reason it was interesting…I mean, I’ve read a little Jane Austen, but I’ve read Frankenstein twice, and I think I read it for the first time–and you mentioned this in an interview somewhere, that it was Brian W. Aldiss who perhaps first suggested that Frankenstein was the first science fiction novel–and it was after reading his history of the field that I thought I should read Frankenstein, as opposed to just relying on what we all kind of know from the miasma of Frankenstein stuff that’s around.

That’s right. And, frankly, the image we get of Frankenstein from movies is very much not the creature that was…well, one thing is that people call the monster Frankenstein, and it’s Victor who is Frankenstein. The creature has no name in the book. And so, yes, I wanted to present the monster, the creature–I prefer to call him the creature–as he is in the novel. He’s incredibly intelligent, he’s agile, he’s strong. He’s becomes a kind of…he educates himself remarkably. He’s incredibly articulate. He speaks very well, which is so weird because we’re not used to that from the movies. And so, one of the things that Viktor warns people against when he tells them about these creatures, is, “Don’t listen to him because he’s so persuasive.” That’s really interesting. And he’s sort of a social critic of human behavior. So I wanted to get into that. In a way…

You know, Aldiss did say that this was the first science fiction book, and I had not read it until I read Aldiss, back in the ’70s. and it seemed to me that if Mary Shelley wrote the first true science fiction novel in English, and Jane Austen was sort of the ancestor of the novel of manners…so these are the two great streams in literature, it seems to me, since the early 1800s to the present. We have the novel of the fantastic, the science fiction novel, and then we have the realistic novel like, you know, Henry James and Virginia Woolf, following In the footsteps of Jane Austen. And so, in a way, cramming these two things together in the same book is really sort of unnatural, but also, to me, fascinating.

I read it again…I read it out loud to my wife for the 150th anniversary of the novel, because we have…I read out loud while she’s cooking because our kitchen’s too small for us to cook side by side. And so, it was very interesting to read it out loud, too, and to say that sort of early 19th century prose, but also the fact that, you know, Mary Shelley was a teenager when she wrote it, nineteen.

Really, eighteen, nineteen years old. And I think it was published when she just turned twenty, right, so…

And I have a daughter who’s eighteen.

Okay. Actually, it was 200 years ago, 200 years ago in 1818.

Right, 200. Yeah, yeah. I just lost half a century there somewhere. So, you’ve talked about how the inspiration for this came about. Just pulling back from it a little bit, is that fairly typical of the way that your story ideas come to you, things sort of colliding and sparks coming off of it?

Often the collision of two things that don’t fit together is a good way to get a story started, it seems to me. And I’ve written a number of works, as I say, that take off from other literary works, but that’s not all the stuff I write, and so…like, my last novel, in 2017, before this one, was The Moon and the Other, which is a science fiction novel set on the moon in the twenty-second century. Very complex future background, lots of technology, I tried to make it as accurate as I could, showing how people might live on the moon, so that one really comes from a different place. And that’s sort of how it works, really.

But yes, the collision of things…to me, it’s always interesting to have things that don’t seem like they ought to go together put together. Or, another way of putting that is, I really like paradoxes. I like when things don’t easily settle themselves out. You know, where all of the…for instance, all of the morality, or the rightness and wrongness, doesn’t all land on one side. I don’t really like stories where there’s the hero and the villain and there’s just no…it’s easy to choose between them and there’s no confusion or complication of that way of seeing things.

Once you have the idea, for this novel or other novels, what does your planning process look like? Do you do a detailed outline? And how does it differ from your short fiction writing?

Well, again, it depends a little bit on the project. With novels, I do quite a bit of outlining and sketches and notes. I will try to figure out what the inciting incident is, the beginning incident, and then have some sense of where it’s going in the end. Although, when I was younger, I always had to know the ending before I could start a story, but now I’m more willing to get started without a firm idea of how it’s going to end. Well, one thing with Pride and Prometheus is I had many things given to me from Frankenstein. I knew I was going to follow Frankenstein’s plot. And so, I know eventually that Victor ends up in the Orkney Islands, there trying to create the female. So, that to me was a place I was going to get to. I knew I was gonna get up in the Orkney Islands when he’s trying to create the bride for the monster. How he gets there and how Mary gets involved in it, that was not all worked out.

But then, those things are also given to you. For instance, one of the things that happened was…I think I mentioned that in Jane Austen novels, the spring for many of the plots, or maybe all the plots, is finding the right mate. You have these young women heroines who are maybe attracted to one man, who…or someone is being courted by one man…but it turns out there’s someone else who is really the person they should be with. And finding the right mate is the crucial decision of a young woman’s life in Jane Austen’s period, of her social class, anyway. And so, what hit me was that in Frankenstein, Frankenstein is about a lonely guy, the creature, who can’t find a mate. And so, he has to find a female who will love him. And then Victor’s part in this is, he has to create this female. And in order to do that, he’s going to have to come up with a female body. So I thought, “Well, gosh, you know, that’s sort of scary. He’s going to meet my character, Mary, who’s a lonely old maid, and, you know, what sort of things could happen?” And so this sort of offers certain possibilities of scenes that I could imagine. And if you have certain scenes you want to write in a narrative, you can connect them, connect the dots really, like beads on a string. You know, I know I’m driving from here to San Francisco, and I know I’m going to stop in Memphis and Kansas City and Denver and Salt Lake City, but I don’t know where I’m going in between. And so, you sort of try to arrange those, and you drive your characters, you know your characters, you know your characters, you know what they want, what they don’t want, the circumstances around them. The circumstances will change, depending on what happens in the story, and then, you know, given who they are, the kind of people they are, how would they react to that and what would they do to respond to it? And so, that can help you plot a story out. That seems to me a pretty natural way to create a story.

One of the interesting things about Pride and Prometheus is you’ve got this Jane Austen…and it’s also, it’s three viewpoints. I guess there’s third person for Mary, and then you’ve got two first persons, you’ve got the creature and you’ve got Frankenstein and all of them…the prose is…it seems to me that it reminds you of the prose of Austen and Shelley without being…trying to really get into that very convoluted early-nineteenth-century style where you can have one sentence that goes on for like a full page, almost.

Right. Well, thank you. I actually spent a lot of time thinking about that. And so…I tried not to completely imitate Jane Austen’s or Mary Shelley styles, which are quite different. And it’s right, you know, Frankenstein is written in first person from the point of view of these characters, and Jane Austen’s novels are all in third person. But I wanted to allude to them, so that someone who is familiar with those books would feel that this was reminiscent of that, without being so convoluted that it would be difficult to read. So that was my take on it. I hope I did that well enough. I’m pretty proud of how I did it, actually.

It’s…you know, in a lot of ways, the writing of a book is a process of discovery and you have to–I’ve said this to my students, that when you write any fiction, that it’s a collaboration between your conscious mind and your unconscious mind. And if you have everything planned out like a, you know, an architect, it seems to me you can stifle your imagination, because you have everything all worked out and there’s no discovery involved. So, I think that you have to depend on…at least, the life of a narrative can come from you allowing your mind to ruminate over something that you don’t really know the answer to. And that…Jim Kelly, my friend James Patrick Kelly, says that if the writer writing a story is never surprised by anything that happens, then no reader will ever be surprised. And it seems to me that, you know, to a greater or lesser degree, that there have to be things that you didn’t plan that turn up on the page.

I don’t know what your experiences is, but haven’t you ever had the experience where something just sort of comes to you as you’re writing that is exactly the thing you needed, and you did not know it, but there it is, and it proves to be much smarter than anything you could have thought up in advance?

Oh, yeah, that happens. Happens all the time.

Yeah. It’s funny how that works. It seems to me that our minds are more complex than we can easily understand.

The book I’m writing now, which is the third book in a series of mine, much to my surprise, there’s this long discussion on God’s relationship to time that pops up in one scene, which I had no intention of the two characters talking about at that time. But that just seemed to make sense. So there it is, so far, anyway. So, yeah. It’s interesting. It’s very interesting the way the writing mind works.

What’s your actual physical process of writing? Did you write this in longhand in a notebook like they might have, Austen and Shelley, or do you write on the computer? How do you work?

I’m a computer writer, a keyboard writer. I’ve been writing on keyboards since, you know, 1970 with typewriters. I never…I used to…I’ve done some longhand writing, but very little. Very little. And I know some writers who say that they can’t think unless they’re writing longhand, but I work with a keyboard. I work with a laptop right now, although I have it connected to a big screen at my desk.

I tend to work at my desk in my home office. Although there have been times when I will, when I’m having trouble, I will say, OK, I’m going to go to Panera Bread or Starbucks and sit there in the corner and try to write, and that’s worked, too. So, whatever it takes to get the work done, I think, is what I need.

And when I’m teaching, I have a lot of other responsibilities, so I can’t always write every day. And I’m not one of those…actually, I think one of the things that’s told to young writers that can be very intimidating to them is that you can’t be a writer unless you write every day. And it seems to me that…it’s certainly good to encourage the habit of writing regularly, okay? I think that that’s absolutely true. If you want to write anything of any length or…you need to be…you have your head in the game regularly, all the time. But I don’t write every day and I never have. There’ve been periods where I’ve written every day for, you know, a couple of months, when I’ve had the time to do that or when I’ve been hot on a project and I want to finish it, but there are other times when I, you know, I’ll write three days a week, okay, or I’ll, between projects, be sitting around reading and playing the guitar and watching bad movies and thinking. So my process…I mean, I do have habits that work for me. I try to be regular in them. But, you know, other people say, “Oh, we have to write, you write the same time of day every day.” Well, I generally will try to work in the morning, but it doesn’t always work that way. So whenever it comes to me to work, then I will work. And sometimes I do have to kick myself in the pants and say, “OK, you need to sit down there. You need to close the door. You need to stare at the screen. You can’t look at your e-mail. You cannot go to Facebook. You are a writer.”

Yeah, that’s…I know that feeling. Deadlines help sometimes, too, to motivate you.

I like deadlines. I know George R.R. Martin, I think, is a writer who hates deadlines and sort of fights against them. I am one who, a deadline focuses my attention, and I like deadlines because it tells me exactly what I have to do. I have to have this done by September 1st, it’ll be done by September 1st. In my entire undergraduate career and graduate career, I don’t think I ever turned in a paper late, because something about it, the idea of being late on it would be worse. I mean, I would just…not so much that I’d get a bad grade, but rather that psychologically I might never get it done if I don’t make it by the date that I’m supposed to turn it in.

What does your…once you have a draft. What does your revision process look like?

Well, I will certainly go over it and make sure it reads smoothly and revise and edit to a degree until I’ve got a fairly polished version of it. But then I will show it to other people who are writers who I trust to give me feedback. And one of them is my wife, Therese Anne Fowler, who is extremely successful. I mean, she’s much more successful than I am. She wrote a novel called Z, a novel of Zelda Fitzgerald, which was a bestseller and made into a TV show on Amazon. And so, she’s a very experienced novelist, and so she gives me feedback. I often talk to her about it over supper. We’ll be working, we’re both writers, and so we’re working and then we have meals together. “How’s your day, dear?” “Oh, you know…” And she doesn’t talk as much about her work as I do, but I often talk about what I’m doing and what the problems are and what’s going on. But then when I get a draft done, I show it to her.

I always ask James Patrick Kelly to read it, and he’s been my faithful critique and critic for, you know, forty years now, really. A very wonderful guy, wonderful writer, so knowledgeable. And other writers who I have regularly…and get feedback…are my friend Richard Butner, who lives here in Raleigh, and Lewis Shiner, a well-known science fiction writer. He lives in Raleigh and we’ve been friends for more than thirty years. Karen Joy Fowler has helped me a lot with my female characters and Gregory Frost…and often actually for a couple of my things, Bruce Sterling, a writer who many people…I mean, back in the ’80s when he was the head cyberpunk and I was labeled as a humanist writer, people thought we would, you know, we hated each other, but that wasn’t the case, even though we disagreed about an awful lot of stuff. But he’s give me some very good readings over the years.

Are there sort of consistent things you find that your readers come back with that you need to…per up?

I usually find, when I have some women readers, that my women characters need attention, OK? And so…I’m trying to do my best. But, you know, I think it’s good to have someone put their eyes on it who has experienced the things that a woman experiences. And so, that to me is a consistent thing that I have had to pay attention to. The editing of…editing things down. I tend to be, in my early drafts, a lot more wordy than I do in the later. As I’ve gotten older, I’m less and less that way, I think. And Jim Kelly has been very helpful with that. He’s a much more efficient writer than I am, and I have to sort of work to get to that point.

What other things? You know, there are sometimes story-logic issues, but generally, my stories, when I get a draft done…I’ve done a lot of time thinking. I don’t write really fast, so it generally has had a lot of thought put into it, and it’s very seldom that I get told something that causes me to drastically change what I’ve written, like the structure or something.

You teach writing. Do you ever find people telling you to do things that you tell your students to do but you overlook in your own writing?

Gosh, probably. One of my colleagues at NC State is a novelist named Wilton Barnhardt, also a wonderful novelist who has given me much, much good advice. He’s not afraid to tell me, you know, but I think as far as the things that I tell my students, it’s not usually so much that, you know.

Well I ask because, you know, I mentor writers. And then when I’m editing my own stuff, I’ll say, nope, there it is, that’s exactly what I told them not to do, and I did it in my first draft.

Well, it’s certainly true that I will make grammar or usage errors that I would complain about to them. I generally…I know the difference between lie and lay, okay, but it’s possible for me to make a mistake there. Or I will sometimes put an apostrophe in its, a possessive its, when it doesn’t belong there.

Yeah, that’s a pernicious one. That just happens sometimes.

Right. It’s, you know, it’s a matter of you writing fast and not thinking.

So once the book goes to the publisher, what does the editing…we should say Pride and Prometheus is from Saga, is that right?

Saga. That’s right? And my previous book, The Moon and the Other, was also from Saga. And that was…my editor there is Joe Monti, who’s is good. I had never worked with them before The Moon and the Other. And actually, I said that I very seldom change structure, but with The Moon and the Other, I sold on the book, and I…he had the whole manuscript. It was finished, you know, before…I thought it was done. And he read it, and we met in New York City, and he said, “You know, it’s a slow start on this book.” It’s a big book. It’s like, 600 pages long, and it’s got four main characters and it alternates point of view between these four characters.

And I said, “Yeah, I know, it starts really slow because I have to do all four characters and they’re in different places, they don’t know each other, it’s complicated.” And so, he said, “Do you know how long it takes before all four characters are introduced?”, and I said, “Jeez, I don’t know. Maybe eighty pages? Seventy pages?” He says, “108 pages.” “Wow. Okay.” And he said, “Is there something you can do?” I mean, he said…also, the first chapter originally was taking place ten years before the body of the book. It was sort of like a prologue. And he said, “Do you have to have that chapter? Can you take it out?” And I said, “I absolutely cannot take out the chapter because it mirrors the last chapter of the book, and there are all these reasons why I just could not do it. There are too many things introduced there that are vital to the storyline.” And then I went home, and I said, “OK, so…” He didn’t say I had to do it, but he said, “Is there anything you do speed up this this book?”

And so I went home, and I thought, “All right, is it possible to take out that first chapter? What happens if I take out the first chapter? There’s things in that chapter I absolutely need. Is there someplace else I could put them?” So, I took the first chapter out, and one thing that immediately became evident is that I would have to rearrange the order of the next six or seven chapters. And so, I did that. And then I had to rearrange what was in those chapters, because the chapters depended on what happened in previous chapters. And then, I had to get the first chapter stuff in there somewhere else. And anyway, it ended up changing the first seven chapters of the book, and considerable revision. And it got much better. I mean, it started much better. And I’m so glad he…he didn’t tell me to do it, he didn’t say, “You have to do this,” but he made me think about it. And it really was vitally important to the book, I think, to do it, to get that chapter moved. And it really made it better.

And I think, you know, new writers sometimes are concerned about the editing process, you know, they’re going to change my deathless prose and all that sort of thing.

Right. Right.

And certainly my experience has been with my editors, Sheila E Gilbert at DAW Books, Hugo Award winning editor, and my experience has been, editors make things better for the most part.

I think they want the book to be as good as it can be. And, you know, you may have some differences of opinion, but it doesn’t help you to be stiff-necked and defensive about things. You know, actually, Christopher, who was in my undergraduate class, was writing the novel…I can’t remember the title of the first novel in the series…but he had it in my, parts of it in my class, and I remember we met in my office one time, and it had a prologue on it, and I felt the prologue was slow to start, and then the first chapter was a completely different situation than the first, than the prologue. And I said, “OK, so you’re opening this story with a frame here. When do you close the frame? Do you close the frame at the end of the book?” Because I hadn’t seen the whole book. He said, “No, I close the frame at the end of the trilogy.” And I said, “That’s not going to work. You need to…if you’re going to have a frame in front of a book, you need to close it by the end of the book. Or at least that’s my strong prejudice. Think about that, okay.” And so, what he did was, he ended up throwing it out. And I don’t know what he did with the material, if it shows up elsewhere, but he changed that. And to me, I thought that was a, you know, I mean, I didn’t make him do it, but that just was my advice for a better opening. And it’s funny, it’s similar to what Joe Monti told me, although it happened before that. So, you know, I guess it helps to be able to listen to things, even if you don’t, in the end, do what the editor says.

Empire of Silence. That’s the first book.

That’s it. Empire of Silence.

Howling Dark is the one that just came out. Well, now we’re getting close to the end, so I want to move to the big philosophical questions. Why do you write? Why do you think any of us write? And why do you and I and others write science fiction and fantasy?

Wow, those are tough questions. I don’t know if I can speak for everyone else, but…

For yourself, then.

Yeah. Frederick Pohl, science fiction writer Frederick Pohl, said science fiction is a way of thinking about things, and I like that definition a lot. It seems to me that you can think about things in terms of, in science-fictional terms, the same kinds of things you can think about in a realistic story, but you do it differently. So if you think about, say, marriage, okay, or death or love or parenthood or something like that, in science fiction you can twist things in a way that sort of exposes the workings or…I think of it sometimes as like a lever that you can shove into the machine and pry it open and see the workings in a different way than a realistic novelist or story writer can, so that one of the appeals of science fiction, is that you can…

The very. the fantastic element. to me. should be essential to the story. And in fact, that’s one of my principles, is that. if I could tell this story without the science fiction or the fantasy element, then I should tell it without it, okay? That it has to be vital to the story, has to be essential to make the point I’m trying to make that is in there. So, you know, in other words, I could…

You know, The Moon and the Other started from me watching my daughter at the daycare center when she was a toddler. And I was watching the kids in the playground, the little kids, two, three years old, playing out back. And it seemed to me that the boys’ way of playing was different from the girls’ way of playing. And I started thinking about, “Well, is that inherent or is this culturally determined, okay? When did they start behaving differently?” And so that got me thinking about the difference between men and women–not that I hadn’t thought about it before, but… and I ended up writing this big novel set on the moon in the twenty-second century about gender issues. And yet, another person would have written a story about a father at a daycare center with his daughter and the other kids, you see? But that’s not what I wrote. I wrote a science fiction novel. So, there’s something about that tropism for the strange, or the fantastic, that I’ve always had, and I think I always will.

I think that, you know…why does anyone write? It’s a very good question. I think it’s something about…trying to figure out the world, it seems to me. Or maybe just to entertain yourself or entertain somebody. There’s an element also of sort of showing off, isn’t there? Where you want everyone to admire you. And so…I remember there was a TV production company that did sitcoms and stuff, and at the end of every show, they’d have this little logo and they’d have a kid’s voice that would say, “I made this!” And I always liked that, because a kid makes things just to make them and to be proud, you know, to sort of say, “I made this myself. No one else made this.” And I still have that kid feeling, you know, “No one else wrote these books. No one else could write these books exactly the way I wrote them. Maybe for better, for worse, someone might have written them better, but I made this book myself,” and I like that, you now?

That is one of the rewarding things about it, for sure.

It’s bad when they reject your story and say, “Oh, my God, that stinks.”.

Yeah, there’s that, too.

Yeah.

Well, that’s kind of the end of our time. So, what are you working on now?

I have a novella that I just told you about that is on submission right now that is a weird kind of thing. It’s about the assassination of President William McKinley in 1901 at a World’s Fair in Buffalo, New York, and it’s also about a trip to the moon in 1901. And it sort of alternates between the realistic historical story and this fantastic scientific romance about the inhabited moon full of Selenites.

I miss that moon.

Yeah. It’s based on a ride that was there at the at the fair, called A Trip to the Moon. It was the first dark ride, if you know what a dark ride is, like at Universal City or Disney World, where they have these rides, you’re in a vehicle and they show you things. So that one’s going out. It’s a kind of political story. I’ve got a ghost story. I wrote my first ghost story and that is on submission right now. And I don’t know, we’ll see what happens with that. You’d think I would have written a ghost story before now, but I didn’t. And who knows? I like to write different kinds of stories. So, you know, if there’s a kind of story I haven’t written yet, I’m thinking, well, what kind of what kind of monster story would I write?

And where can people find you online?

Oh, I have a Web site…and also, there’s a…I have a pretty active Facebook page, which is open to the public and has lots of things on there. You can find things about me. And I’m in the bookstores. Look for Saga books.

OK, well, I think that’s the end of our time, so, thanks so much for being a guest on The World shapers. That was a fun conversation.

Well, thank you very much. I certainly didn’t lack for things to say. I hope I didn’t get too far off the bat.

No, no, it was great. So, thanks a lot, and bye for now.

Take care.